Barking Owl

Barking OwlNinox connivens | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Least concern (IUCN 2021) |

| Australia: | Not listed (EPBC Act 1999) |

| Victoria: | Critically Endangered (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| FFG: | Listed Action statement No. 116 |

The Barking owl (Ninox connivens) is regarded as being a moderately large owl about 40cm in length; it has bright yellow eyes and almost no facial mask, which is typical of the ‘hawk owl’ family. Viewed from the front its chest and abdomen are white with brownish-grey vertical streaks. Upper wings and back are brown-grey with white spots, flight feathers and tail are barred.

It can be distinguished from the larger Powerful Owl which has barring across its front rather than vertical streaks (Juvenile Powerful Owls have some sparse vertical streaks but not as obvious as the Barking Owl). The Powerful Owl also has more barring across its back rather than the white spots of the Barking Owl.

Barking Owl (left), Powerful Owl (right).

Two subspecies of Barking Owl Ninox connivens are recognised from mainland Australia;

- Ninox connivens connivens (eastern Australia, southern Australia and southwest Western Australia.

- Ninox connivens peninsularis (northern part of Western Australia, Northern Territory and far north Queensland).

Distribution

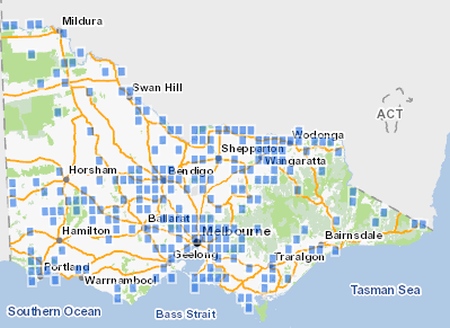

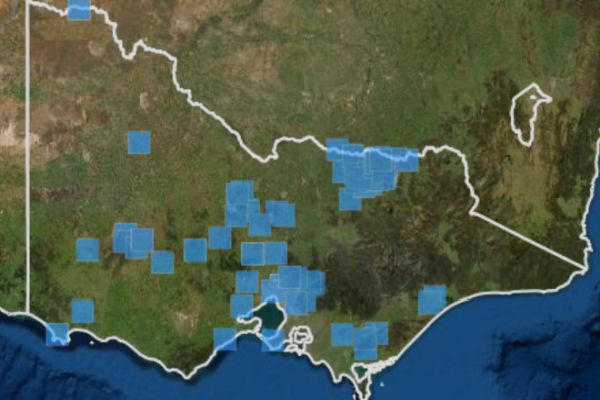

In Victoria, the Barking Owl could have an estimated population size of fewer than 50 pairs (Silveira 1997) with North East Victoria being the remaining stronghold area. Once recorded in association with forest woodland areas across much of Victoria, particularly the western part of Great Dividing Range to the Grampians, North East Victoria and the ranges to the north east of Melbourne, the Barking Owl is now considered extremely rare in many areas of Victoria.

Ecology & Habitat

The Barking Owl inhabits open woodland forest habitats where forests adjoin farmlands, effectively creating an open farmland-woodland mosaic. Use of forest interior habitats is less common; in particular the use of extensive areas of moist forest habitat is uncommon with drier woodlands, particularly box-ironbark woodlands being the most frequented habitat.

Habitat preference is strongly bias towards areas that provide a high density of large trees greater than 60cm diameter and a high density of hollow trees of a range of sizes, including large hollows greater than 15cm diameter which are suitable nesting places for Barking Owls.

Surveys conducted in 1998-1999 found that hollows were two three times more prolific at sites where Barking Owls were recorded compared to no owl sites. It was also noted that Barking Owl habitat has a strong spatial association with hydrological features such as rivers and wetlands (Taylor & Kirsten 1999).

Nesting occurs from July to October, during which time the Barking Owl uses large tree hollows producing between 2-3 young.

Hunting and diet

Barking Owls have a preference for hunting in open woodland/forest edge habitats. Foraging behaviours include; Short stay perch hunting (changing position after 1 min), hawking (short bursts of erratic flying) and long stay perch hunting. They have been observed hunting in the early evening using ‘short stay perch hunting’ whilst it is still light and using long stay perch hunting, scanning for prey in the dark. They have varied calls ranging from a Wuk-wuk hooting call, a low growling call, a dog like woof woof call and a human-like scream (Hodgson 1996, Simpson & Day 1996).

Diet comprises small mammals (rabbit, gliders, rodents), birds, bats, and insects, however information on diet still remains limited and may include other prey. The relationship between occurrence of hollows in trees and Barking Owl habitat also applies to habitat for the production of prey species, some which are also dependent on hollow trees eg. gliders, possums, rosellas, bats etc.

Movement

Barking Owls are thought to be sedentary, probably remaining in the same territory all year around and from year to year. They have been observed to hunt reasonably close to their nest site (1-2km) but distances may alter depending on habitat quality Studies have found home ranges in semi arid areas averaging 2,000 ha (Kavanagh and Bamkin 1995).

Population Status

Nocturnal studies across the western Victoria in 1998-1999 recorded Barking Owls at only 11 sites (4.3%) of 257 carefully selected sites and found only 6 sites (8%) of 75 sites where they had been reported during 1980’s and 1990’s which could indicate a continuing deterioration in the species status (Taylor & Kirsten 1999). A similar trend of decline has been recorded in New South Wales (NPWS 2003) and in areas of North East Victoria where there was a population decline in the Chiltern - Mt Pilot National Park of 60% between 2003 to 2005 (Schedvin 2008).

Results from surveys conducted by Taylor & Kirsten (1999), highlight the need for closer examination of sites previously recorded on the Victorian Wildlife Atlas. There are many sites within the South West of Victoria for example that had previous records which were not confirmed in the 1998-1999 survey, raising the possibility that Barking Owls could have been lost from those locations (see below).

Approximate locations at which Barking owls were located (adapted from Taylor & Kirsten1999)

- State Forest – Glenelg River, Balmoral area

- State Forest - Glenelg River, Balmoral area

- Wash Tomorrow Game Reserve, Toolondo area

- State Forest – Lake Lonsdale, Stawell area

- State Forest – Ledcourt, Ledcourt area

- State Forest – Burnt Creek, Dunolly area

- State Forest – Burnt Creek, Dunolly area

- Cobboboonee State Forest, Portland area

Approximate areas of Victoria’s South West where previous Atlas records exist but remain unconfirmed as of 1999 and are now possibly in doubt

- Lower Glenelg N.P.

- Casterton area

- Grampians N.P. (northern end)

- Little Desert N.P.

- Buangor S.P

- Avoca area

- Enfield Forest area

- Lerderderg S.P. and nearby areas

- Brisbane Ranges N.P.

- Eastern end of Otway Range, including (Great Otway N.P.)

- Carlisle S.P.

- Western end of Otway Range – Kennedys Creek area

Threats

Being a top order predator the Barking owl can be impacted upon by loss of prey species caused through habitat degradation and fragmentation, logging, firewood harvesting wildfires and excessive burning. Loss of suitable hollow bearing trees has a twofold impact on both nesting sites and habitat for prey species such as birds and small mammals. Retention of vegetation containing hollows is particularly important on the forest- private farmland ecotone.

Fox predation and competition for prey species by foxes and feral cats have been identified as threatening processes in NSW. Feral honey bees invading hollows, secondary poisoning from pesticides and mortality from collision with barbed wire fences and wires have also been identified as potential threats (NPWS 2003)

Decline of non-native prey such as rabbits, which may have filled a prey shortage in areas suffering a reduced diversity of prey, for example sites where habitat has been degraded and native prey has been diminished.

Conservation & Management

A common theme from both research and natural resource management sectors is the need to improve understanding of this species abundance, distribution and ecological requirements.

There is a need to clarify the status of Barking Owls across Victoria. There are a number of old records which require detailed survey to ascertain if Barking Owls are still present e.g. sites from Table1.

Suggested management priorities

Adapted from Schedvin (2008)

- Promote resilience of barking owl populations to climate change - ensure that the compound effect of isolation on the population is remedied.

- Strategic long-term planning of conservation actions - habitat conservation actions may also enable greater conservation gains for barking owls if they are prioritised in relation to the relative impact for effort.

- Improve the quality of habitat in existing owl territories.

- Increase the size and number of barking owl populations.

- Ensure existing habitat protection prescriptions are adhered to by forest managers

- Promote prey populations.

- Increase the area of native vegetation in high productivity areas.

- Promote the formation of natural hollows.

- Promote understorey regeneration.

- Apply Barking Owl conservation measures into to LGA planning.

- Minimize the impact of future wildfires.

Barking Owls and fire management

The greatest benefits for barking owls can be derived from habitat rehabilitation efforts if they are begun during the mopping up phase of fire suppression operations. For example, burning snags and hollow trees should in the first instance be extinguished, wherever possible, rather than felled. This will be of benefit to barking owls and many of their prey that also rely on tree hollows for shelter and breeding sites Schedvin (2008).

Specific Conservation Actions

Key management partners include; Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP - Forest Management), Parks Victoria, Catchment Management Authorities and Local Government Areas where Barking Owls are known to occur.

- Protect all known Barking Owl sites within the parks and reserves system. In larger parks and reserves, identify Barking Owl Management Areas (BOMA’s) of at least 500ha of continuous suitable habitat that can be managed to be free of significant disturbances. In smaller conservation reserves, protect as much suitable habitat as possible and endeavour to obtain co-operative management from adjoining landowners.

- Planning permit applications (subdivision, native vegetation clearing, mining etc.) will be assessed to evaluate and prevent or minimise loss or deterioration of Barking Owl habitat.

- All confirmed nesting and roosting sites utilised recently and frequently (based on reliable observation or physical evidence such as pellets or wash) located outside BOMA’s will be protected by a 3ha SPZ around the site and a 250-300m radius.

- Private landowners will be encouraged to protect scattered trees on farmland.

- Monitor selected pairs of Barking Owls to determine details of habitat use, population trends and site fidelity.

- Monitor populations to determine success of management actions.

- Establish BOMA’s on public or private land.

- Avoid the development of intensive recreational facilities near known nesting and roosting trees and discourage public access to breeding areas.

- Conduct surveys to locate as many resident pairs of Barking Owls as possible across land tenures throughout the main range of the species.

- Locate all known Barking Owl sites within the parks and reserves system.

Projects & Partnerships

Research

In 2006 a short 8 nights survey was carried out in suitable habitat along the Murray River at Walpolla Island in Victoria’s North West. The survey was focused in the vicinity of where Barking Owls had been recorded in 1995 but no Barking Owls recorded (Hurley 2006).

A long term study was undertaken in a semiarid area (620mm annual rainfall) in the Pilliga State Forest in northern NSW which found home ranges averaging 2,000 ha (Kavanagh and Bamkin 1995).

A post-fire assessment of the January 2003 wildfires in the Chiltern - Mt Pilot National Park in North East Victoria assessed impacts on barking owls identified that the population had declined by 60% to 12 breeding pairs (Schedvin 2005). In 2007, four years after this initial assessment, another assessment of the Chiltern-Mount Pilot barking owl population was undertaken. This revealed that barking owl pairs continue to be lost from the area. The population is now down to 10 active sites, of which 9 are breeding pairs. If the current trend continues Barking Owls will be completely lost from the area within the next 30 years (Schedvin 2008).

Suggested future research priorities

Adapted from Schedvin (2008)

Barking Owl Carrying Capacity - in order to implement a landscape approach to barking owl conservation, it is important to be able to evaluate the barking owl carrying capacity of different environments (i.e., how many breeding barking owl pairs will an area support?

Post-fire recovery monitoring - continued monitoring of barking owl populations is critical Given the continued decline

in the population of the area where studies have been carried out

Promotion of hollows - it is more likely to be the availability of hollows for prey that is limiting Barking Owls. There needs to be a study to investigate the efficacy of promoting hollow formation in eucalypts (perhaps through injuring trees).

References & links

DELWP (2020) Provisional re-assessments of taxa as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria 2020, Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Victoria. Taxa re-assessment list pdf

FFG Threatened List (2023) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024

Hodgon J. (1996) Behaviour and Diet of the Barking Owl Ninox connivens in South-eastern Queensland, Australian Bird Watcher 1996, Vol.16 (8), 332-338.

Hurley, V. (2006) A short survey of the Murray River from Wentworth to Lock 9 for Barking Owls Ninox connivens, winter 2006. Report to the Mallee Catchment Management Authority, Vctor G. Hurley, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Mildura VIC.

IUCN (2021) BirdLife International. 2016. Ninox connivens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22689394A93229752. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22689394A93229752.en. Downloaded on 19 March 2021.

NPWS (2003) Draft Recovery Plan for the Barking Owl. New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, Hurstville, NSW.

Simpson & Day (1996) Field Guide to the birds of Australia, sixth edition, Penguin Books Australia Ltd.

Schedvin, K. (2005). Impact of the 2003 Eldorado Fire on Barking Owls (Ninox connivens connivens), North East Victoria. Technical Report, Department of Sustainability & Environment.

Schedvin, N. (2008) Post-fire recovery of the barking owl Ninox connivens population in the Chiltern- Mount Pilot National Park and surrounds. Author: Natasha Schedvin, Zoologist, Wildlife & Conservation Sciences, June 2008, Zoos Victoria 2008 –Bushfire effects on Barking Owls.

Silveira ,C.E. (1997) 'Targeted assessments of key threatened vertebrate fauna in relation to the north-east and Benalla-Mansfield Forest Management Area (NE FMA), Victoria: Barking Owl Ninox connivens.' Arthur Rylah Institute, Heidelberg.

Taylor I. R., Kirsten I. (1999) Targeted Barking owl (Ninox connivens) survey for the West Region Comprehensive Regional Assessment, Johnstone Centre Research in Natural Resources & Society Report No. 135, Charles Sturt University, Albury, NSW.