Common Bent-wing Bat

Common Bent-wing BatMiniopterus orianae | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Sub-class: | Eutheria |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Sub Order: | Microchiroptera |

| Family: | Miniopteridae |

Southern Bent-wing BatMiniopterus orianae bassanii | |

| Australia: | Critically endangered (EPBC Act) |

| Victoria: | Critically endangered (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| FFG: | Listed |

| Zoos Victoria Figthing Extinction profile |

| Southern Bent-wing Bat - National Recovery Team | |

Eastern Bent-wing BatMiniopterus orianae oceanensis | |

| Australia: | Not listed EPBC Act |

| Victoria: | Critically endangered (FFG Threatened List 2023) |

| FFG: | Listed |

The name Common Bent-wing Bat is really an generic name for what is actually three separate sub-species (previously referred to as Miniopterus schreibersii) which exist in Australia, none of which are common.

Southern Bent-wing Bat (Miniopterus orianae bassanii - southern subspecies) considered critically endangered and distributed in south-western Victoria extending into the south-east corner of South Australia.

More information: Southern Bent-wing Bat - National Recovery Team

Eastern Bent-wing Bat (Miniopterus orianae oceanensis - eastern subspecies) also known as the Large Bent-wing Bat, occurring near coastal eastern Australia from the northern tip of Queensland down the east coast including New South Wales and extending to central Victoria.

Northern Bent-wing Bat (Miniopterus orianae orianae -northern subspecies) found in the northern part of Western Australia and Northern Territory.

Identification

The Common Bent-wing Bat has dark brown to redish brown fur above, grey-brown fur underneath and pale brown areas of bare skin. Head and body length 52mm-58mm, forearm 45-49mm. It has a short muzzle, high crowned head, broad rounded ears and small eyes. It has a long wing length being nearly two and half times longer than the head and body. A diagnostic feature of the wing structure is the terminal phalanx (segment) of the longest finger, which is more than three times as long as the previous phalanx (Dwyer 1983, Hall & Woodside 1989, Menkhorst. & Lumsden 1995).

Identification is best carried out by non-handling techniques and certainly not by entering known roost sites. A preferred method of identification is by recording and analysing call sequences as each bat species has its own frequency range.

Identification caution

Unlike most other species of insectivorous bats the Common Bent-wing Bat roosts exclusively in caves or cave like structures rather than trees. In particular, the Southern Bent-wing Bat is reliant on only one or two caves for rearing young and a handful of caves for roosting, some of which are visited by humans which reduce their suitability as roosting habitat.

Distribution

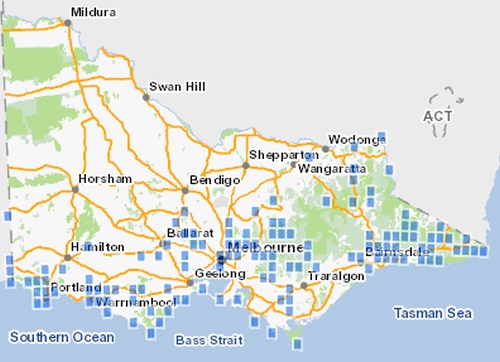

Victorian Distribution of Common Bent-wing Bat (GROUP)

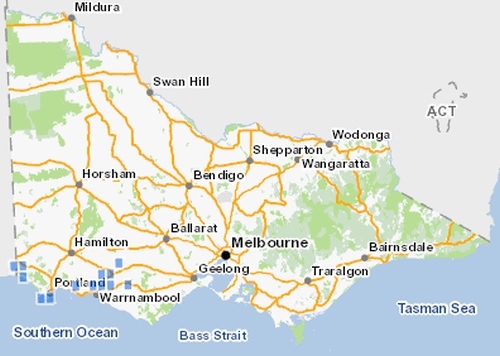

Victorian Distribution of Southern Bent-wing Bat

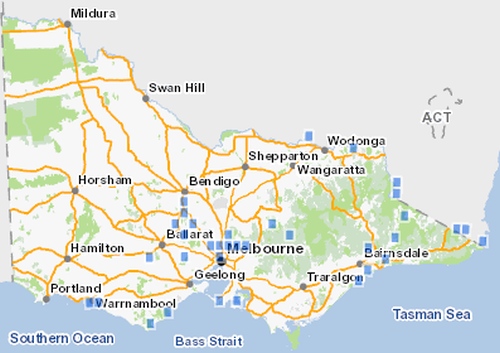

Victorian Distribution of Eastern Bent-wing Bat

Ecology & Habitat

The Common Bent-wing Bat can live up to 20 years. Habitat preference is associated with the availability of foraging areas and proximity to suitable roosting caves, for example many of the roosting caves are located near coastal cliffs, old mine shafts and roock caves.

Movement

Foraging areas include forested areas, Volcanic Plains, wetlands and coastal vegetation including beaches. Distances travelled from roosting caves is often less than several kilometres for small microchiropterans and is dependent upon reproductive condition, for instance lactating females travel shorter distances than pregnant females or non-breeding females. Where roost sites are located in sub-optimal foraging habitat the distances travelled may increase perhaps up to 30km. Pregnant females undertake much longer journeys when they fly to maternity caves for giving birth (Kunz & Lumsden 2003).

Breeding

Breeding takes place in late May and early June, however the onset of gestation is delayed through winter until August. By late November to December females congregate at maternity caves where a single young is born to each female. A strong bond is developed between mother and young, which persists beyond the first flight to when the young leave the cave 'en mass' (Hall & Woodside 1989). By February to March the young are free flying and tend to roost in their own caves, the adult females return to the same roosting caves each year after giving birth at the maternity cave whilst adult males tend to stay resident in the adult roosting cave throughout the year.

Caves

a roosting cave. Image: Gabrielle Lanman

Different caves are used depending on the season, reproductive stage and sex of the bat. For instance adult males, pregnant females and juveniles tend to group at separate caves during particular times of the year. Females have specific requirements for giving birth and rearing young, which includes a dome type cave, which retains warmth and humidity for development of the young. These caves are referred to as maternity caves.

Maternity caves

There are only two recognised maternity caves in Victoria;

- The Southern Bent-wing Bat Miniopterus schreibersii bassanii maternity cave near Warrnambool.

- The Eastern Bent-wing Bat Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis maternity cave in East Gippsland near Bairnsdale.

Feeding

The Common Bent-wing Bat is nocturnal and uses echolocation (emission of ultrasonic sounds) for navigation and feeding. Recording and analysing call sequences provides a means of identifying a particular species of bat as each species has its own frequency range.

Feeding is carried out during flight and prey is caught in the tail or wing membrane and transferred to the mouth whilst in flight, sometimes insects are caught in the mouth (Hall & Woodside 1989). Diet consists of a range of night flying insects eg. Order Diptera (mosquitos, midges), Lepidoptera (moths), Orthoptera (crickets), Coleoptera (beetles), Hemiptera (bugs), Hymenoptera (ants). Microchiroptera play a major role as the nocturnal predator of night flying insects, many of which are a nuisance to humans. It is estimated the Common Bent-wing Bat can consume about 25% of its 15 gram body weight per meal and may eat two or three meals per night, therefore a population of 1000 bats could consume several kilograms of insects per night.

Roosting

On return to their roosting caves they cluster at preferred microclimates within the cave. During this time they carry out grooming and rest by lowering their body temperature to the ambient temperature and go into a torpor state for a period of hours. Over the winter months when insect activity is low and food is not readily available they go into a deep hibernation and select the coolest caves and coolest part of the cave. During this time their body temperature can be down to 20C, which limits the loss of body fats through winter (Speakman & Thomas 2003). They are particularly prone to disturbance when at rest as valuable reserves of body fat are consumed if disturbed.

Threats

There has been a severe decline in the Southern Bent-wing Bat. The total population size was estimated to be approximately 200,000 several decades ago, now it is down to about 40,000. The winter count in 2010 only found about 25,000 although this low number may be attributed to the fact that further winter roosting sites are yet to be located.

Human disturbance

Probably the most severe impact on a population is caused through human disturbance at roost sites because it can result in abandonment of a cave. During a state of torpor and particularly over winter when the bats are in a deep hibernation human disturbance in the form of noise, lights and handling can cause a rise in body temperature, which uses up body reserves. If there is repeated exposure this can result in loss of body reserves beyond recovery and the bat is likely to die.

Disturbance at a maternity cave is considered a major threat because it can impact on the breeding success of the population.

Disturbance during summer has been identified as a problem in some areas where tourists and holidaymakers enter caves, which is likely to result in bats fleeing the cave in daylight and using valuable energy reserves and making them more prone to predators. Repeated disturbance can result in abandonment of the cave. Disturbance has been identified as an issue in some areas along the coastline where otherwise perfectly good caves have been rendered unsuitable, sometimes forcing bats to use much smaller caves and crevices that are marginal habitat, which can only support low numbers (Lumsden 1998).

The use of different caves is an integral part of the ecology of this species, therefore it should not be assumed that disturbance which leads to abandonment of a cave will result in the bats simply moving to another cave. It will most likely cause mortalities and have wider implications for the populations roosting, social organisation and mating behaviour.

Insecticides

The impact of insecticides on insect numbers and therefore food for the Bent-wing bat is unknown, however ingestion of insects treated with insecticides may cause secondary poisoning. Direct ingestion of insecticides can occur particularly when grooming fur or wings that have been exposed to spray.

Impacts on foraging habitats

Habitat change mainly through loss of trees and loss of connectivity between landscape elements may reduce range, as generally bats are reluctant to cross open landscapes (Racey & Entwistle 2003). Loss of wetlands through drainage can impact on feeding areas.

Drought

Low rainfall impacts on wetland condition and food availability for insectivorous bats. Low rainfall can also reduce the movement of water through caves, reducing the humidity in caves which has been observed to cause mortality of bats.

Windfarm developments

The positioning of wind turbines near known or potential feeding areas and in bat flight lines has been raised an issue and is relevant to several proposed windfarms in the South West region of Victoria. Wind turbines located near roosting caves (particularly near a maternity cave) raises the likelihood of contact between rotating blades and bats, particularly as there is a concentration of bats from around the region and there is frequent flying to and from the maternity cave when raising young. A full assessment of potential impacts on bats should be part of any development proposal, which includes assessment of flight paths between the maternity cave and roost sites, between maternity cave and feeding sites and between roost sites and feeding areas.

Introduced predators

In Victoria, predators include the introduced Black Rat, Feral Cat, and Red Fox.

Cave Management

There is a need to protect the microclimate inside maternity caves which under natural conditions maintains a constant temperature and level of humidity. Caves which are modified by enlarging or closing off vents can alter the microclimate. In some cases caves need to be protected from erosion and inappropriate use of heavy machinery which may cause a cave to collapse.

Conservation & Management

Conservation of Southern Bent-wing Bat and Eastern Bent-wing Bat in Victoria

Cave entrance management

Protection of caves, both the maternity cave near Warrnambool and the various roosting caves which need to be free of human disturbance. Gates, barriers or fencing out areas from human disturbance is required at many sites. Gates or bars must allow movement of bats and it has been found that in order to design a grill to prevent humans it will also be detrimental to the movement of bats. The provision of a free space above any grill at least 66cm high is required for the movement of bats in and out of a cave (Lumsden 1998). Before any gate or barrier is installed it is recommended that advice from bat ecologist be obtained.

Mines management

Management of disused mines may provide suitable habitat for bats and can play a role in expanding or substituting roosting habitat. In Australia there are approximately 31species of bat which use caves and derelict mines, including the Common Bent-wing Bat. Assessment of disused mines for bat presence and gauging levels of human interference are necessary steps in determining what measures are required for protection. A comprehensive publication by the Australian Centre for Mining Environmental Research provides guidelines on how to identify and protect bat conservation values in disused mines (Thompson 2002).

Priority management measures

Improve understanding of the distribution of the Common Bent-wing Bat by onducting surveys in caves and disused mines across Victoria as part of a state wide survey effort.

Ensure important roost sites are regularly monitored for evidence of predation by introduced predators and control measures implemented.

Monitor important roost sites for human disturbance an implement control measures, including physical barriers, education and signage where undue disturbance is occurring.

Monitoring known over-wintering sites to determine usage, numbers and potential threats to sites.

DELWP can assist Local Government Planning by ensuring important roost sites are included into planning overlays so sites are recognised when developments are proposed.

Monitor habitat at roosting caves/mines to ensure they remain accessible to bats and are not overgrown by weeds or blocked off by collapse of mine entrance.

Discourage dumping of rubbish in caves.

For the North East Forest Management Plan and the East Gippsland Forest Management Plan implement a Special Protection Zone buffer of 100 m around all breeding and roosting caves and mines and known over-wintering sites.

Contribute to a state-wide register of roosting sites (caves, mines, rock crevices, tunnels, culverts etc). This register would contain a range of information relating to the site including the need for intensive management such as weed removal or vegetation management.

Key measures and findings at the Southern Bent-wing Bat maternity cave

2010

In 2010 the cave was fenced off to exclude heavy machinery causing cave collapse. Stock proof fence around cave entrances.

Results from Winter monitoring in 2010 found that during winter the bats migrate to a large number of caves.

In 2010, approximately 23,500 Southern Bent-wing Bats were observed in Victoria and South Australia. This is considerably less than the estimated 40,000 known from summer counts, suggesting further roosting sites are yet to be located.

2012

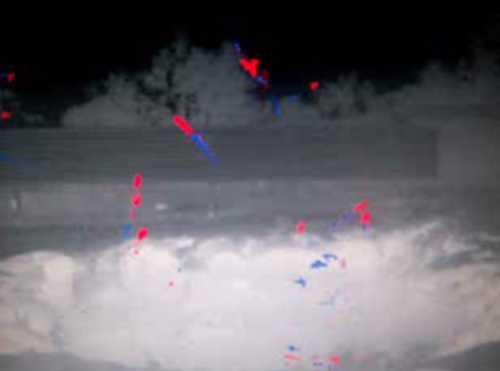

In 2012 two summer surveys were completed at the maternity cave using thermal imaging camera to count bats exiting the cave each night. These surveys focused on gaining estimates of the female population and also to determine the survival rate of pups to juveniles.

It is estimated that 10-15,000 adult Southern Bent-wing Bats used the cave. Autumn migration monitoring was undertaken at the maternity cave using Anabat recordings to determine the timing of the migration to roosting caves.

A 3D image of the maternity cave roof was created to determine the approximate surface area of the roof. This information is necessary to determine estimates of adult bats and pups by counting bats over a small known area and extrapolating out to the surface area.

Monitoring of overwintering caves was carried out in Victoria and South Australia in July 2012 with 33 known Victorian habitat caves. Approximately 4200 bats were counted but more information is required on the location of winter roosting areas. Further searches for caves that support Southern Bent-wing Bats is needed. It is important to note the survey teams use passive recording techniques so as to minimise disturbance to overwintering bats.

The South Australian count only managed to locate approximately a third (15,478) of their estimated population during winter.

2013

A Management Plan for the maternity cave near Warrnambool was completed in 2013 with approved actions implemented to protect the only known Victorian breeding cave and maternity population.

The summer monitoring program consisted of two maternity cave monitoring events aimed at determining the female Southern Bent-wing bat population estimates as well as the rate of juvenile survival and species recruitment. A thermal imaging camera was used to film the evening exit of bats.

Bat call recorders have been installed in the maternity cave and a significant non-breeding roost cave since March 2013 to better determine bat movements and cave usage. A further five non-breeding caves are being monitored monthly with count estimates and limited bat call recordings (since March / April).

2014

Two summer counts were undertaken. Surves to discover where the majority of the Southern bent-wing Bat population roosts over the winter months carried out.

Undertake research to determine if wind farms pose a potential threat to the Southern Bent-wing Bat.

Projects & Partnerships

- Victorian Speleological Association

- Parks Victoria staff

- Species experts

- Department of Environment, Land Water and Planning

- Landholders with bat caves who assisted with access

- Glenelg Hopkins CMA

Southern Bent-wing Bat - National Recovery Team

References & Links

- AFD (2016) Australian Faunal Directory, Miniopterus schreibersii, Department of Environment, Australia. Accessed 27 May 2016.

- Dwyer, P. D. (1983) Common Bent-wing Bat Miniopterus schreibersii, Complete book of Australian Mammals, Ed. Strahan, R., Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- FFG Threatened List (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) , Victoria.

- Hall, l. S. & Woodside, D. P. (1989) Vespertilionidae. Pp. 871-886 in Walton, D.W. & Richardson, B.J. (eds) Fauna of Australia. Mammalia. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service Vol. 1B

- Kunz,T.H. & Lumsden, L.F. (2003) Ecology of Cavity and Folage Roosting Bats, In; Bat Ecology, pp 3-89, (Eds). Kunz, T.H. & Fenton, M.B., The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London

- Lumsden, L. (1998) Inspection of the Cumberland River Cave and its Colony of Common Bent-wing Bats, Miniopterus schreibersii, with Management Recommendations, A Report to Parks Victoria, Angahook – Lorne State Park, July 1998.

- Menkhorst, P.W. & Lumsden, L.F. (1995) Common Bent-wing Bat, In; Mammals of Victoria, (Ed). Menkhorst, P.W., Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, Australia.

- Menkhorst, P. (2001) A field guide to the mammals of Australia, Common Bentwing Bat, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, Australia.

- Racey, P.A. & Entwistle, A. C. (2003) Conservation Ecology, In; Bat Ecology, pp 680-743, (Eds). Kunz, T.H. & Fenton, M.B., The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Southern Bent-wing Bat Species Profile & Threats database, Department of Environment, Accessed 27 May 2016.

- Speakman,J.R. & Thomas, D.W. (2003) Physiological Ecology and Energetics of Bats, In; Bat Ecology, pp 430-489, (Eds). Kunz, T.H. & Fenton, M.B., The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Thompson, B. (2002) Australian Handbook for the Conservation of Bats in Mines and Artifical Cave-Bat Habitats, Australian Centre for Mining Environmental Research, Kenmore, Queensland.

- VBA (2016) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria.

More Information

Cave dwelling bats in Victoria

- Southern Bent-wing Bat Miniopterus schreibersii bassanii

- Large Bent-wing Bat Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis (central and eastern Victoria)

- Eastern Horseshoe Bat Rhinolophus megaphylus (eastern Victoria)

- Lesser Long-eared Bat Nyctophilus geoffroyi

- Large Footed Myotis Myotis adversus

Southern Bent-wing Bat - National Recovery Team

SWIFFT Seminar notes - New insights into the secret lives of bats

Please contribute information regarding the Eastern Bent-wing Bat or Southern Bent-wing Bent-wing Bat in Victoria - observations, images or projects. Contact SWIFFT