Eastern Barred Bandicoot

Eastern Barred BandicootPerameles gunnii | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Peramelemorphia |

| Family: | Peramelidae |

| Status | |

| Australia: | Endangered EPBC Act listed |

| Victoria: | Endangered (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| South Australia: | Endangered (NPW Act 1972) |

| Tasmainia: | Not threatened (DPIPWE) |

| Victorian FFG: | Listed: Action Statement No. 4 (pdf) |

| Species profiles | |

| Australia: | Atlas of Living Australia profile |

| EPBC Act: | SPRAT species profile |

| Zoos Victoria Figthing Extinction priority species |

The mainland Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunnii) is a small (~750g) marsupial with a long-pointed nose. Colour varies from yellowish-brown above to cream underneath and a white tail and feet. The most distinguishing feature is the three or four pale bars on the hindquarters.

Distribution

Formerly widespread throughout western Victoria, the mainland Eastern Barred Bandicoot was considered 'Extinct in the Wild' in Victoria (DEPI 2013) but due to the success of the recovery effort, was reclassified to Endangered in 2021. The last wild population was located in Hamilton, Victoria which suffered a steady decline throughout the 1970s and 80s. In 1988 the EBB Recovery Team was formed. The first action was to catch as many of the remaining wild bandicoots as possible to start a captive breeding and release program.

Eastern Barred Bandicoots are extinct in South Australia but still occur in Tasmania.

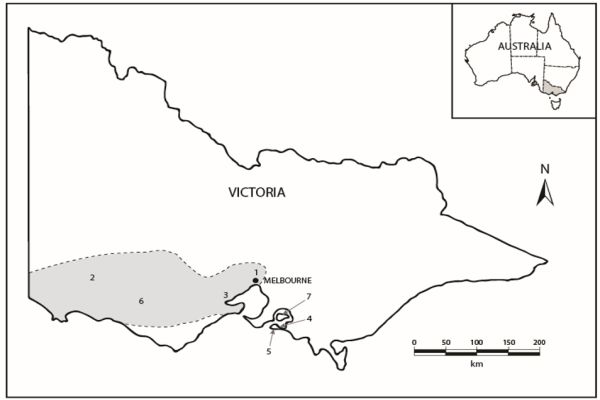

Historic distribution of the Eastern Barred Bandicoot in Victoria (grey shaded area). Established populations in order of establishment: 1) Woodlands Historic Park 2) Hamilton Community Parkland 3) Mt Rothwell 4) Churchill Island 5) Phillip Island 6) Tiverton 7) French Island. Image credit: A. Coetsee

Ecology & Habitat

Natural habitat comprises tall, dense native grasslands and grassy woodlands, although remnant populations have adapted to modified habitats provided there is adequate shelter and effective control of introduced predators. Feeding is carried out at night and being omnivorous the diet varies according to the availability of food which includes beetles, crickets, worms, caterpillars, and plant material such as berries, tubers and bulbs.

Grassy woodlands at Hamilton Community Parklands. Photo credit: A. Coetsee

Males have larger home ranges than females and on Churchill Island were found to have overlapping homeranges with other males, whereas females had less home range overlap, suggesting territoriality between females. Breeding can occur throughout the year but is more prolific in the cooler months with breeding success dependent upon conditions such as the availability of food and cover. With an average litter size of 2-3 and a capacity to have up to 5 litters per year, populations have the potential to expand rapidly under ideal conditions, particularly as offspring can reproduce from 3-4 months of age. In reality however, optimal conditions are infrequent and high mortality has retarded any significant expansion. During drought conditions population recruitment is low.

During the cooler months there is a peak in the number of pouch young, this declines as the weather gets warmer. It is thought this peak is due to the longer nights in the cooler months allowing more time to forage and the availability of high energy food items such as beetle larvae due to the less compact soils into which the bandicoots can dig.

Threats

Major threats include a loss of native grassland and grassy woodland habitat of which over 99% has been lost in Victoria, and predation from the introduced red fox.

Cats are a lesser threat but pose a threat through direct predation and toxoplasmosis. EBB populations have successfully established on Phillip and French Islands in the presence of feral cats.

Domestic and feral cats are a threat to the Eastern Barred Bandicoot through direct predation and disease. We do not know if the French Island EBB in this camera trap image managed to get away from the pouncing cat. Image credit: A. Coetsee

Conservation & Management

Management is carried out in accordance with a Recovery Plan that identifies the key actions necessary for the recovery of the species. Actions are carried out through co-operation between partners who work together through the EBB Recovery Team. The Eastern Barred Bandicoot Recovery Team has members from Conservation Volunteers Australia, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), Glenelg-Hopkins CMA, Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Interpretation Centre, National Trust of Australia (Victoria), Parks Victoria, Odonata Foundation, Phillip Island Nature Parks, Tiverton Rothwell Partners, University of Melbourne and Zoos Victoria.

During the 1990s reintroductions occurred at two fenced reserves (Woodlands Historic Park and Hamilton Community Parklands) and also into the wild at sites without protective fencing (‘Mooramong’ near Skipton, Lake Goldsmith Wildlife Reserve near Beaufort, Floating Islands Nature Reserve near Colac and on a private property ‘Lanark’ at Branxholme). Success varied at all sites with drought conditions having a negative impact. However, all non-fenced sites declined, mainly due to fox predation, and became locally extinct.

The recovery plan now focuses on sites that can be maintained fox-free either by using predator exclusion fences or fox-free islands. Self-supporting populations protected by predator exclusion fences have been established at Woodlands Historic Park, Hamilton Community Parklands, Mt Rothwell and Tiverton. As well as three fox-free islands (Churchill, Phillip and French).

The success of the recovery program to-date has meant that the long-term captive breeding program was closed down in 2021, as it was no longer needed.

Current Release Sites

Fenced Sites

Woodlands Historic Park

In 1989, Woodlands Historic Park became the first reintroduction site. Whilst the population quickly established and increased to up to 900 animals a long-term drought, difficulties maintaining the site fox-free and overgrazing led to the population declining rapidly and eventually became extinct.

In 2012, Conservation Volunteers Australia partnered with Parks Victoria to manage the reserve for EBBs. During 2012, work focused on a rabbit, fox and feral cat eradication program, followed by on-going monitoring to ensure no foxes were present. Once the reserve was fox-free, 45 Eastern Barred Bandicoots were released in 2013. Some came from the captive population with others coming from Hamilton Community Parklands and Mt Rothwell to give the best genetic makeup for successful breeding.

Several infrared monitoring cameras have been installed at Woodlands which enable volunteers and project officers to observe the bandicoots acting naturally during the night hours. These citizen science styled activities are enabling the public to get involved in threatened species activities from their own homes. The general public can volunteer for this through the Conservation Volunteers Australia website.

The Eastern Barred Bandicoot reintroduction project at Woodlands is a significant contribution to the long-term conservation of the species. The population increased to an estimated 498 (CI: 342-726) EBBs in November 2015. However, a lengthy drought and over grazing by macropods caused the population to decline. The site is now macropod free and the grasslands have been restored to their best condition in decades with the grazing pressure gone and some good seasons of average rainfall. The bandicoot population is now recovering well with digs found across the reserve.

Through funding and support from DELWP Woodlands is about to build a new predator exclusion fence. This upgrade from the existing fence will help the site work on threatened species for at least 30 years. The site will reduce in size slightly but pick up more valuable open red gum grassy woodland vegetation which will provide better habitat and increase bandicoot numbers.

Actions

- Monitor and exclude foxes and cats.

- Maintain predator exclusion fence.

- Undertake EBB population monitoring.

- Manage grazing pressure to prevent overgrazing and loss of EBB habitat

- Weed removal.

- Monitor habitat condition.

- Involve volunteers in population monitoring

Volunteers looking for serrated tussock in the Themeda triandra grasslands at Woodlands Historic Park. Photo credit: T. Scicchitano

Hamilton Community Parklands

Hamilton Community Parklands was the second EBB reintroduction site, with the first release occurring in 1989. Like Woodlands, the Hamilton population established quickly but the population became extinct after a prolonged drought and difficulties maintaining the site fox-free. In 2007, after the fence was upgraded, and the site became fox-free, 24 EBBs were released and have been present ever since.

The Hamilton Community Parklands is a 107-ha reserve surrounded by a predator exclusion fence.

The population is known to fluctuate considerably with rainfall being a factor in breeding and holding capacity. The impact of foxes (even one or two) though the fence was seen to have dramatic consequences on the population.

The site has been used extensively to translocate EBBs to other locations. In 2017 animals were taken to Phillip Island and 2019 released at French Island. Animals will continue to be harvested to support the recovery teams priorities.

In 2021 the Victorian State Government supplied funding to replace the predator exclusion fence In February 2022 construction on the new fence commenced. This difficult process involved building a new fence while maintaining the existing enclosure introduced predator free, an incredibly difficult task.

Bandicam

Bandicam was officially switched on as a livestream from the Hamilton Parklands Safe Haven on October 3, 2022 thanks to funding through the Victorian Government. To date, there have been more than 4200 views of the livestream, over 603.5 hours of vision watched, and the YouTube channel streaming the camera has 60 subscribers. The project to install Bandicam was undertaken by Glenelg Hopkins CMA with support from DEECA and Southern Grampians Shire Council.

The idea behind Bandicam evolved after the successful installation by Glenelg Hopkins CMA of Platycam, a livestream of the Grangeburn in Hamilton, Victoria, which was the first ever livestream of platypus in the wild. With Hamilton's role in the successful reintroduction of the Eastern Barred Bandicoots to the reserve, it was thought a livestream in the reserve to showcase the bandicoots could similarly work.

Bandicam is a livestream camera stationed on a pole within the reserve area that is operated by a solar-powered battery. The camera angle can be moved to view different areas of the reserve and capture the Bandicoots going about their activities in a natural environment.

Along with Bandicoots, the local wildlife and birdlife have been captured on the livestream. A highlight of the streaming has been capturing baby bandicoots on the livestream.

The livestream of Bandicam can be viewed at: www.bandicam.com.au or on YouTube - Bandicam Live Stream.

Actions

- Maintain free of introduced predators to protect EBB population.

- Manage native and introduced herbivore numbers to prevent overgrazing and loss of EBB habitat

- Manage environmental weeds.

- Involve local community in Eastern Barred Bandicoot activities.

- Undertake population monitoring at least twice per year.

%20habitat%20600%20126%20px.jpg)

Hamilton Community Parklands. Photo credit: Jon Lee

Mt Rothwell

Mt Rothwell has recently expanded to over 500 ha of private land dedicated to conservation. A total of 24 Eastern Barred Bandicoots were first released at Mt Rothwell in 2004. The population is established within the predator exclusion fence area and is thought to range between about 1000 and 2000 animals depending on seasonal conditions.

Mt Rothwell in partnership with Melbourne University established a captive outcrossing program which allowed the integration of new genetics to the mainland population.

Rabbit grazing is an ongoing issue across the property. Over the past 10 years Mt Rothwell has tackled and significantly reduced the rabbit population with a third of the property now being rabbit free. Further efforts and funding are required to remove the rabbits entirely to increase carrying capacity, as areas treated has improved the habitat quality for EBBs that can now be found across portions of the reserve.

A new boundary fence partially funded by DELWP and the Odonata Foundation has a 50-year anticipated lifespan and should ensure the likelihood of breaches are minimised and the protection of endangered animals such as EBBs can be preserved for the lifetime of the fence.

Mt Rothwell is primarily run by Odonata Foundation staff and local volunteers.

Actions

- Manage grazing pressure to prevent overgrazing and loss of EBB habitat

- Monitor EBB population

- Monitor habitat condition

- Remove rabbits

- Maintain and monitor fence

Tiverton

Private philanthropists linked to Mt Rothwell, Tiverton Rothwell Partners purchased a 1000 ha property in western Victoria. “Tiverton”, at Dundonnell, (25 km north-east of Mortlake). Tiverton is dominated by basalt 'stony rises', which are lava flows from past volcanic activity. With funding from Zoos Victoria, Odonata Foundation and Tiverton Rothwell Partners, construction of a 17.5 km of predator exclusion fence commenced in 2016. This has created the fourth and largest Eastern Barred Bandicoot reintroduction site on the mainland. In a first for the Recovery Team, the reintroduction site is also an operating Merino wool property. Sheep grazing is considered essential to open up the grasslands to allow other grassland plants to flourish.

The fence was completed in 2018. The unforgiving rocky basalt country made access difficult, and it took about 18 months to completely remove all foxes and cats. Finally in spring of 2020, 40 outbred EBBs (25% Tasmanian, 75% mainland) were released. By 2022 EBBs were being encountered widely across the property and appear to have successfully established. Once fully established this population should be the largest of the four reintroduced populations within the historic range of the EBB.

Actions

- Maintain predator exclusion fence

- Monitor and exclude foxes and cats

- Monitor EBB population (abundance, health and genetic diversity)

- monitor habitat condition

Eastern barred bandicoot release at Tiverton. Photo credit: Odonata Foundation

Islands

Churchill Island

Churchill Island is only 57 hectares but free from predators such as foxes and feral cats thanks to an on-going predator eradication program by Phillip Island Nature Parks. The island is also rabbit free. On Sunday 16th August 2015, Phillip Island Nature Parks in conjunction with the Eastern Barred Bandicoot Recovery Team released 16 EBBs (8 males and 8 females) onto Churchill Island, near Phillip Island. Half of the released bandicoots came from the Zoos Victoria captive population and the other half from Mt Rothwell. A second release of 4 animals from Mt Rothwell occurred two months later.

The release has been a huge success with the population increasing to 120 individuals over the first two years. Bandicoots are now widespread across the island. The population fluctuates between 100 and 170. The island has been used for research projects on EBB diet, on EBBs as ecosystem engineers, to improve models to estimate abundance and survival, and to understand the rate of successful integration of new animals and their genes into established populations. And critically for getting support for releases to the larger offshore islands, a demonstration site for community members from Phillip and French Islands to see for themselves what to expect from an EBB release.

Churchill Island monitoring updates

Actions

- Monitor EBB population

- Maintain island as feral cat, fox and rabbit free

Aerial view of Churchill Island. Photo credit: Phillip Island Nature Parks

Phillip Island

The Phillip Island releases build on the successful releases at Churchill Island. On 20 October 2017 a release of 44 EBBs into the wild took place on the Summerland Peninsula, Phillip Island. Additional releases in November and December 2017 brought the total number released to 67. Animals came from Churchill Island (40), the captive breeding program (11), Woodlands (10) and Hamilton (6). This release was made possible by the declaration in 2017 that Phillip Island was fox-free and by the hard work of the Eastern Barred Bandicoot Recovery Team including all its members.

The key differences with Phillip Island for the recovery of EBBs was the much larger area of suitable fox-free habitat, around 9000 ha, but also the presence of feral cats that pose a threat both through predation and disease. The population has successfully established and is expanding across most of Phillip Island.

For more information see Phillip Island Nature Parks story map and the Phillip Island monitoring updates.

Actions

- Monitor EBB population

- Intensive monitoring and control of introduced predators to reduce the density of feral cats and maintain a fox free environment

Aerial view of Summerlands Peninsular, Phillip Island. Photo credit: Phillip Island Nature Parks

French Island

French Island is Victoria’s largest island. Whilst it has always remained fox-free there is a feral cat population on the island that has been controlled since 2010 by Parks Victoria and the French Island Landcare Group.

After gaining support from the French Island community, the biggest and most logistically challenging Eastern Barred Bandicoot translocation happened in October 2019, on French Island. The translocation began on Thursday 10th October on Churchill Island, with Phillip Island Nature Parks leading the collection of 40 EBBs to take to French Island the following morning. Later that afternoon the Churchill Island bandicoots were joined by 16 EBBs bred in captivity, taking the total number of EBBs released on 11th October to 56 (32 male: 24 female) and 30 pouch young.

Two weeks later a further 18 EBBs from Hamilton Community Parklands were released bringing the final number of EBBs released to 74 (44 male: 30 female) and 34 pouch young.

The population is monitored by 40 cameras within the release site as well as biannual trapping and reports from community members. The bandicoots are doing well and are now widespread across the island.

For more information:

Actions

- Monitor EBB population

- Monitor and control feral cats

This project took 12 years of community engagement to come to fruition. Many French Island community members helped carry and release the EBBs into the release site - Bluegums. Photo credit: Zoos Victoria.

Captive breeding program

A captive breeding program managed by Zoos Victoria provided both insurance against extinction and a means of producing animals for reintroduction into the wild. The captive breeding program operated from 1988 to 2021, producing and raising ~1200 bandicoots, but has now been closed down as it is no longer required.

Captive breeding was managed by at Zoos Victoria since 1991 with Dubbo Western Plains Zoo, Healesville Sanctuary, Kyabram Fauna Park, Melbourne Zoo, Monarto Zoo, Serendip Sanctuary, Taronga Zoo, Taronga Western Plains Zoo and Werribee Open Range Zoo contributing to captive breeding. Zoos Victoria played a key role in implementing the Australasian Species Management Program and provides veterinary care for the species. Education and awareness raising of the species and its recovery is another ongoing key focus.

Zoos Victoria has also conducted research programs at Melbourne Zoo and Werribee Open Range Zoo including husbandry and breeding success, predator recognition and avoidance training, and mate choice preference trials. Results published in 2016 indicate that females are choosing mates, and those paired with their preferred males had a shorter time to pregnancy and more pregnancies than other females.

Whilst the captive breeding program has closed down, there are a handful of older animals kept in retirement homes at Woodleigh School's Brian Henderson Wildlife Reserve, Serendip Sanctuary and Healesville Sanctuary.

Captive breeding has now ceased because it is no longer needed. The reintroduced populations are sufficiently large that the EBB is once again secure and doesn’t need a captive insurance population. However, when the captive breeding program was in operation it had the following actions:

- Managed captive populations to meet population targets and provide genetically suitable bandicoots for release.

- Coordinated the captive program as part of a meta-population, moving animals into and out of the captive program, fenced and island sites, to best manage numbers, behaviour and genetics.

- Coordinated breeding at multiple sites throughout the 33 year program including Healesville Sanctuary, Kyabram Fauna Park, Melbourne Zoo, Monarto Zoo, Serendip Sanctuary and Werribee Open Range Zoo, as well as long-term care at a number of ‘retirement’ locations post-breeding.

- Partner with the Recovery Team to release and monitor Eastern Barred Bandicoots at fenced and island locations.

- Conduct research into bandicoot conservation, ecology, health and management.

Research

Female Mate Choice

Chris Hartnett, University of Melbourne investigated whether the reproductive success of captive eastern barred bandicoots improved when females were permitted to choose their mate. She determined female preferences by measuring how much time they spent interacting with two different males, and whether they showed behavioural signs of receptivity. Females were then paired with either their preferred or non-preferred male. Time to conception and number of pouch young produced was recorded. Chris found that females paired with their preferred male were more likely to produce young and conceived earlier. Research paper.

French Island Trial Release

A trial release of 18 non-breeding Eastern Barred Bandicoots occurred on French Island in July 2012 to determine the suitability of French Island for bandicoots. Rebecca Groenewegen from Melbourne University monitored bandicoot survival, movement and dispersal until the program was completed in 2014 and any surviving bandicoots were captured and returned to Zoos Victoria. The study concluded that French Island has suitable habitat for eastern barred bandicoots, but cat predation and toxoplasmosis were identified as sources of mortality. Research paper.

Gene Mixing and fitness

A project at Mt Rothwell led by Andrew Weeks of Melbourne University has demonstrated the benefits of introducing genetic diversity from Tasmanian Eastern Barred Bandicoots with mainland Eastern Barred bandicoots to restore genetic diversity to the mainland population. Restored genetic diversity will help the mainland EBB adapt to the changing environments it will encounter over coming decades. These outbred animals are now being established across Mt Rothwell, founded the new population at Tiverton and will be introduced across all EBB reintroduction sites over the coming years.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma disease is a parasite of cats which is spread in their faeces and can remain in the ground for up to 18 months under optimal conditions. Bandicoots are exposed to the disease through consumption of invertebrates that have consumed the infective stage of this parasite.

A project to determine the extent and impact of toxoplasmosis, a disease carried by feral and domestic cats, was conducted by Kath Adriaanse (University of Melbourne MVSci student and Melbourne Zoo Vet) on Phillip Island from the time of the release of animals at this site in late 2017. It found that a high proportion (>90%) of feral cats showed exposure to this disease and concluded that environmental contamination with this protozoan parasite was likely. Subsequent post-mortem and field blood sampling surveillance of bandicoots at this site carried out by Melbourne Zoo Vet Department has showed that around 20% of dead EBBs recovered from roadkills on Phillip Island are positive for toxoplasmosis. This data and results of blood sampling suggest most EBBs that are exposed will die within weeks of this exposure. Our current understanding is that on Phillip Island the reproductive potential of bandicoots is sufficient to overcome the current high rate of mortalities from Toxoplasma. Further studies are also being conducted on French Island, a second site where cats are present and bandicoots (dead and alive) with toxoplasmosis have been recorded.

Eastern Barred Bandicoots as ecosystem engineers

A research project by Lauren Halstead at Deakin University investigated the role Eastern Barred Bandicoots play as ecosystem engineers. The research was based on Churchill Island. Measurements of soil turn over; soil moisture and soil compaction were collected. It was estimated that an individual eastern barred bandicoot can digs ~487 small foraging pits per night, displacing ~13.15 kg of soil in winter. It is likely EBBs play an important role as ecosystem engineers with their digging decreasing soil compaction and increasing soil moisture. Research paper.

Further details: The Conversation - One little bandicoot can dig up an elephants worth of soil a year and our ecosystem loves it.

Eastern Barred Bandicoot dig. Photo credit: A. Coetsee

Predator aversion training

Rachel Taylor, University of Melbourne, undertook research to determine if Eastern Barred Bandicoots can recognise cats as predators and be trained to avoid them in the wild. This research involved exposing captive EBBs to cat odour and urine and found that EBBs did not recognise cat scent but could be trained to avoid it. Research paper.

Guardian Dogs

For thousands of years guardian dogs have successfully protected livestock around the world. More recently, Little Penguins in Victoria and Blue Crane chicks in Africa have thrived under the watchful eye of ever-alert canine bodyguards. The potential for these dogs to protect Australia’s threatened species from invasive predators is only just being realised.

A program to use Maremma dogs to protect Eastern Barred Bandicoots from foxes has been developed and is now being trialled at two locations in Victoria. The first release site was set up at a National Trust of Australia (Victoria) conservation reserve near Skipton in western Victoria. In December 2020, 20 bandicoots were released into the wild along with two Maremma guardian dogs. In November 2021 another 20 bandicoots were released into a Dunkeld Pastoral Company owned property reserved for conservation near Dunkeld. It is expected the trial will continue until the end of 2022 when it will be wound down and results analysed and published in the year following. The project is being led by Zoos Victoria in partnership with the EBB Recovery Team and University of Tasmania. More details.

One of the Guardian Dogs deployed at Dunkeld. Photo credit: Zoos Victoria

Establishment of bandicoots on Churchill Island

Anthony Rendall, Deakin University, quantified habitat use by the eastern barred bandicoots, immediately after translocation to Churchill Island. The island has a mix of open woodlands and open pasture, providing a range of habitat conditions considered appropriate for nesting and foraging. A total of 16 bandicoots were radio-tracked for 30 days after release. Males were found to move further after release and have larger overlapping home ranges compared to females that had smaller home ranges and limited overlap, suggesting intra-sexual territoriality among females. Both sexes initially used structurally complex habitats for nesting and foraging but as they became more established, increased their use of open habitats for foraging. Research paper.

Diet of bandicoots

Ella Loeffler, Deakin University, looked at the foraging ecology of EBBs introduced to Churchill and Phillip Islands. Microscopic analysis of faeces revealed that bandicoots exhibit an omnivorous diet, consuming a broad range of invertebrate, plant and fungal material. Invertebrate taxa commonly identified in the diet included earthworms, beetle adults and larvae, ants, cockroaches, spiders and caterpillars. Notably, crabs were also found in bandicoot diet, indicating the species’ ability to adapt to novel environments. Seasonality appeared to be the main factor driving variation in diet, suggesting that the species is likely to feed opportunistically on seasonally abundant food items.

Following Ella’s work, Angie Symon, Deakin University, assessed how the composition of bandicoot diet varies across Victoria. This work compared sites within the historic distribution of bandicoots, at Hamilton Community Parklands and Woodlands Historic Park, with translocation sites outside of this range, at Churchill Island, Phillip Island, and French Island. This research determined that bandicoot diet differed compositionally between all sites, with clear differences between sites within and outside their historic range. In historic range sites, bandicoot diet was characterised by millipedes, caterpillars and fungi, whereas diet outside of this range frequently included ants, skinks and spiders. These differences in dietary composition between sites suggest bandicoots opportunistically feed on what is available at each site and are capable of adapting their dietary intake based on this.

Predator behavioural changes in response to feral cats, comparing Churchill, Phillip and French Islands over time

Tahlia Townsend, Deakin University, looked at the population ecology and behaviour of eastern barred bandicoots on Churchill Island (foxes and cats absent) and Phillip and French Islands (foxes absent, cats present). Tahlia found that eastern barred bandicoots were able to coexist with feral cats and may be using temporal avoidance behaviours to do so, meaning that bandicoots are more active during periods that cats are less active.

Improving analytical models to estimate density and other demographic parameters in bandicoots

Rebecca Groenewegen, University of Melbourne, is undertaking a PhD that will improve the analytical models that are used to estimate population density, survival and other demographic parameters. Challenges for these models include trap saturation, sex bias in trappability and difficulties estimating abundance and survival of juveniles which are rarely captured but represent an important life stage influencing population growth or decline.

How to integrate genes into established populations

Henry Petch, University of Melbourne, is completing a Masters investigating the effectiveness of releasing EBBs into established populations which will inform the best strategies for undertaking genetic rescue of this inbred taxon. By integrating new genes from the Tasmania subspecies, not only does this increase genetic diversity, but is an effective way of tracking the success of individuals contributing to future generations in their new home. The project is happening on Churchill Island and Hamilton. .

More Information

- Eastern Barred Bandicoot - National Recovery Plan 2021

- DELWP Eastern Barred Bandicoot species profile

- Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Mainland) (environment.gov.au)

- Zoos Victoria Eastern Barred Bandicoot species profile

‘Warron’ Eastern Barred Bandicoot recovery newsletters

The ‘Warron’ newsletter is no longer produced by the Recovery Team but provides a history of the long-term efforts to save the Eastern Barred Bandicoot from extinction. This species was recognised to be in severe decline back in the 1960’s and it is only through hours of dedicated work that the Eastern Barred Bandicoot has now been able to recover from the brink of extinction.

- Issue 1 1992 pdf

- Issue 2 1993 pdf

- Issue 3 1993 pdf

- Issue 4 1994 pdf

- Issue 5 1994 pdf

- Issue 6 1995 pdf

- Issue 7 2001 pdf

- Issue 8 2001 pdf

- Issue 9 2002 pdf

- Issue 10 2004 pdf

- Issue 11 2005 pdf

- Issue 12 2006 pdf

- Issue 13 2008 pdf

- Issue 14 2009 pdf

- Issue 15 2010 pdf

- Issue 16 2011 pdf

- Issue 17 2012 pdf

- Issue 18 2013 pdf

- Issue 19 2014 pdf

- Issue 20 2015 pdf

- Issue 21 2016 pdf

- Issue 22 2016 pdf

- Issue 23 2017 pdf

Other Resources

Book

Bouncing Back - An Eastern Barred Bandicoot Story by Rohan Cleave, lllustrated by Coral Tulloch CSIRO Publishing

Related Videos

Release of Eastern Barred Bandicoots at Hamilton Community Parklands, April 2016 (DELWP)

Eastern Barred Badicoot at monitoring station - Woodlands Historic Park, Video from Conservation Volunteers

Release of Eastern Barred Bandicoot at Churchill Island, August 2015. Source: Zoos Victoria.

Zoos Victoria - How dogs and sheep are saving bandicoots from extinction, December 2020.

The Eastern Barred Bandicoots recovery program 2020 - Zoos Victoria.

Art

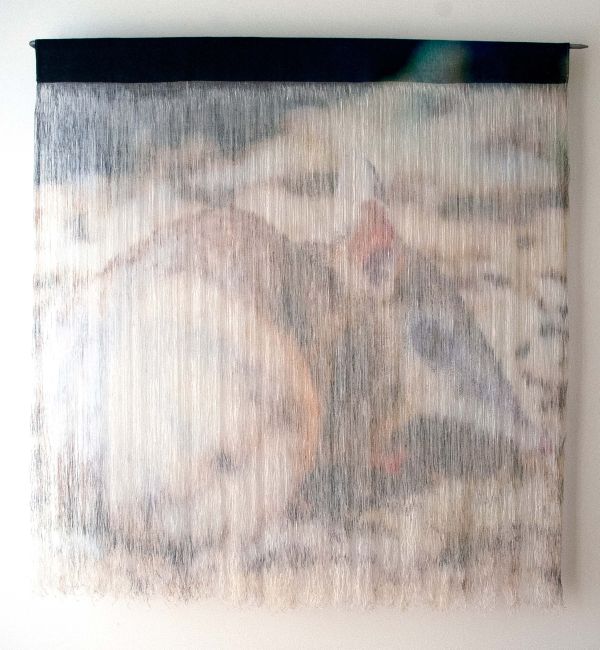

By a thread – Eastern Barred Bandicoot II, 2019 Artist: Jane Burns

Water-based, non-toxic, solvent free pigment ink on linen fabric, linen thread, stainless steel 94 x 94 x 8.5 cm.

This art work depicts the precarious state of the Eastern Barred Bandicoot. Will this species continue to disappear?