Malleefowl

MalleefowlLeipoa ocellata | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Megapodiida |

| Status | |

| Australia: | Vulnerable |

| Victoria: | Vulnerable (FFG Threatened List) |

| FFG: | Action statement No. 69 |

The Malleefowl Leipoa ocellata is a ground-dwelling bird about the size of a domestic chicken (to which it is distantly related). The family Megapodes are unique amongst birds in that their eggs are buried and incubated by external sources of heat such as heat from the sun, geothermal activity, or decomposing leaf litter.

Distribution

The Malleefowl occupies semi-arid mallee scrub on the fringes of the relatively fertile areas of southern Australia, where it is now reduced to three separate populations, located in the Murray-Darling Basin, the area west of Spencer Gulf along the fringes of the Simpson Desert, and the semi-arid fringe of Western Australia's fertile south-west corner.

In Victoria, Malleefowl were once widespread in mallee shrublands in the north-west, in central Victoria, and as far south as the Brisbane Ranges and Melton near Melbourne (Campbell 1884, 1901; Mattingley 1908). Within the past century, the Malleefowl has undergone a marked reduction in its range.

Preferred habitat is semi-arid mallee eucalypt woodlands on sandy soils, but also occur, or once occurred, in a range of other to arid shrubland communities on (Garnett & Crowley 2000).

Ecology & Habitat

Malleefowl are shy, wary, solitary birds that usually fly only to escape danger or reach a tree to roost in. Although very active, they are seldom seen as they freeze if disturbed, relying on their intricately patterned plumage to render them invisible, or else fade silently and rapidly into the undergrowth (flying away only if surprised or chased).

Pairs occupy a territory but usually roost and feed apart: their social behaviour is sufficient to allow regular mating during the season and little else.

In winter, the male selects an area of ground, usually a small open space between the stunted trees of the Mallee, and scrapes a depression about three metres across and just under a metre deep in the sandy soil by raking backwards with his feet. In late winter and early spring, he begins to collect organic material to fill it with, scraping sticks, leaves and bark into wind-rows for up to 50 metres around the hole, and building it into a nest-mound, which usually rises to about 0.6m above ground level. The amount of litter in the mound varies, it may be almost entirely organic material, mostly sand, or anywhere in between.

After rain, he turns and mixes the material to encourage decay and, if conditions allow, digs an egg chamber in August. The female sometimes assists with the excavation of the egg chamber, and the timing varies with temperature and rainfall. The female usually lays between September and February, provided there has been enough rain to start organic decay of the litter. The male continues to maintain the nest-mound, gradually adding more soil to the mix as the summer approaches (presumably to regulate the temperature).

Males usually build their first mound (or take over an existing one) in their fourth year, but young males tend not to achieve as impressive a structure as older birds. Malleefowl are generally thought to mate for life, but exceptions are not unknown. Although the male stays nearby to defend the nest for nine months of the year, they can wander at other times, not always returning to the same territory afterwards.

Females lay a clutch of anywhere from two or three to over 30 large, thin-shelled eggs, mostly about 15; usually about a week apart. Each egg weighs about 10% of the female's body weight, and over a season it is common for her to lay 250% of her own weight. Clutch size varies greatly between birds and with rainfall. Incubation time depends on temperature and can be anywhere between about 50 and almost 100 days.

Hatchlings use their strong feet to break out of the egg, then lie on their backs and scratch their way to the surface, struggling hard for five or ten minutes to gain 3 to 15cm at a time, and then resting for an hour or so before starting again. Reaching the surface takes between 2 and 15 hours. Chicks pop out of the nesting material with little or no warning, eyes and beaks tightly closed, then immediately take a deep breath and open their eyes before freezing motionless for as long as 20 minutes.

The chick then quickly emerges from out of the hole and staggers or rolls to the base of the mound, disappearing into the scrub within moments. Within an hour it will be able to run reasonably well; it can flutter for a short distance and run very fast within two hours, and despite not having yet grown tail feathers, it can fly strongly within a day.

Chicks have no contact with adults or other chicks: they tend to hatch one at a time and birds of any age ignore one another except for mating or territorial disputes.

Threats

Climate change: Malleefowl are particularly vulnerable to the increasing frequency and severity of drought that has resulted from climate change. Breeding season monitoring in the 2002 drought revealed there was virtually no breeding in Victoria. Low breeding numbers were also recorded in the dry years of 2006 and 2007 (Benshemesh and Stokie 2013).

Habitat loss: the main Malleefowl areas in Victoria are now located in areas of parks and reserves. Widespread clearing of suitable Malleefowl habitat has resulted in fragmentation of habitat making populations more susceptible to threatening processes. Reconnecting isolated areas of habitat and protecting remaining habitat are essential for the species long term survival.

Fire: wildfire fire frequency, intensity and seasonality can severly impact on Malleefowl. With many populations now surviving in isolated remnants large scale fires have the capacity to wipe out entire populations. Breeding rarely occurring in habitats that have been burnt within 15 years (Tarr 1965, Cowley et al. 1969). Breeding densities are highest in habitat which has not burnt for 40 or more years although a mosaic of long unburnt and recently burnt habitat is favourable.

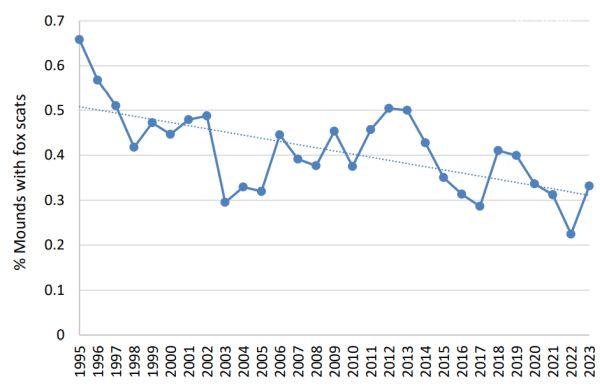

Predation: the Red Fox is listed the major threat in the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Malleefowl Action Statement, Signs of fox activity are regularly recorded in field monitoring. Fox scats were collected at 517 mounds in the 2012 Malleefowl Recovery Group surveys (Benshemesh and Stokie 2013). Feral cats are also recognised as a predator species (Benshemesh 2007).

Competition: grazing from rabbits can denude vegetation and deprive Malleefowl of food and shelter. Kangaroos can also be an issue in high populations densities.

A full account of threats is elaborated in the National Recovery Plan for Malleefowl. Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia Benshemesh (2007).

Conservation & Management

The Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act) Malleefowl Action Statement lists a number of important actions for long term conservation of Malleefowl. There is an active National Recovery Team and a National Recovery Plan for Malleefowl .

In Victoria, 18 key parks and reserve areas have been identified as requiring some level of management which include some or all of the following key actions:

- Assess threats to Malleefowl from foxes and fire.

- Where necessary establish a monitoring grid based on existing methodology.

- Monitor nesting activity on monitoring grids established Mallee-wide.

- Prepare a management plan for medium sized reserves in the Mallee and incorporate actions specific to Malleefowl conservation.

In Victoria, implementation of the above actions is undertaken by Parks Victoria, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning depending on land tenure and volunteer organisations such as the Malleefowl Recovery Group.

Annual monitoring of populations began in the late 1980s and over the years there has been increased government involvement and support, coupled with strong community and volunteer interest. This effort culminated in the 2008/09 season when the Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group (VMRG) monitored 1,169 mounds at 37 sites using up-to-date data-capture methods and analyses (Benshemesh & Stokie 2009).

The Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group is dedicated to the preservation of the Malleefowl, volunteers undergo training in bush craft, data collection techniquea and participate in collecting data from nest sites within defined grids in the Mallee area of Victoria. This group along with other groups is involved with revegetating areas adjacent to known Malleefowl habitat and connecting areas of habitat.

Malleefowl management locations x Local Government Areas

HINDMARSH SHIRE

Big Desert State Forest - managed by DELWP (additional actions to those listed above)

- Conduct an aerial survey in the Big Desert Bushfire area of 2002.

- Ensure management plan includes the need for monitoring Malleefowl population.

Big Desert Wilderness - managed by Parks Victoria

- Conduct an aerial survey in the Big Desert Bushfire area of 2002.

- Ensure management plan includes the need for monitoring Malleefowl population.

Little Desert National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

- Input into Wimmera Fire Operation Plan protection of Malleefowl habitat as outlined in the Little Desert NP Fire Ecology strategy.

Wyperfeld National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

HORSHAM RURAL CITY

Little Desert National Park - managed by Parks victoria

Mitre Lake Flora & Fauna Reserve - managed by Parks victoria

Mount Arapiles - Tooan State Park - managed by Parks victoria

LODDON SHIRE

Wychitella Nature Conservation Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria in conjunction with Wedderburn Conservation Management Network (additional actions to those listed above)

- Undertake informal nest mound counts, to be recorded in accordance with VMRG monitoring protocols.

- Plan to re-introduce birds from other sources to boost genetic pool once threats have been managed.

- Revegetate areas adjacent to known Malleefowl habitat and connect areas of habitat.

MILDURA RURAL CITY

Berrook State Forest - managed by DELWP (additional actions to those listed above)

- Assess the threat of fire regime and foxes to this population and ensure management plan includes the need for monitoring Malleefowl population.

Bronzewing Flora & Fauna Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria

Dennying Channel Bushland Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria

Hattah - Kulkyne National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

- During 2012/13 investigate the establishment of a reintroduced / translocated population by La Trobe University.

- ARI investigated the effectiveness of fox control in increasing the Malleefowl population at Hattah Kulkyne NP in cooperation with Parks Victoria.

Murray - Sunset National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

- During 2012/13 investigate the establishment of a reintroduced / translocated population by La Trobe University.

Timberoo State Forest - managed by DELWP North West Forests

Wyperfeld National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

SWAN HILL RURAL CITY

Annuello F.F.R - managed by Parks Victoria

O'Brees Block - managed by DELWP North West Forests

Wandown Flora & Fauna Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria

WEST WIMMERA SHIRE

Little Desert National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

- Input into Wimmera Fire Operation Plan to ensure protection of Malleefowl habitat as outlined in the Litte Desert NP Fire Ecology strategy.

YARRIAMBIACK SHIRE

Paradise Flora & Fauna Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria

Wathe Flora & Fauna Reserve - managed by Parks Victoria

Wyperfeld National Park - managed by Parks Victoria

Release of captive bred Malleefowl in July 2008 into previously burnt and restored habitat in Wyperfeld National Park.

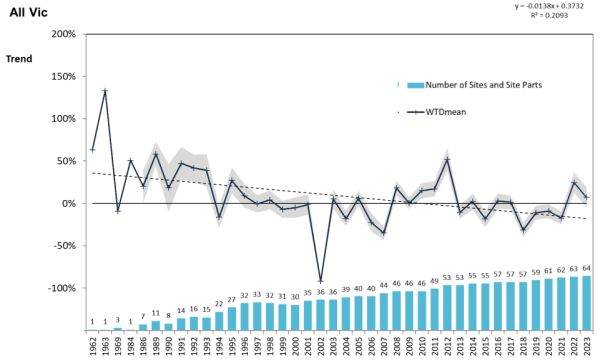

Malleefowl monitoring

In 2023 the Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group (VMRG) visited 1694 Malleefowl mounds. Of all the mounds that were monitored 203 were active in 2023. Breeding numbers were lower than the previous season but still higher than several of the previous years. 2012 recorded the highest breeding rate in the past 20 years. The increase in 2022 may have been attributed to the slightly better than usual autumn-winter rainfall. 2023 was considered good conditions early in the season but drying out in September may have caused a decline in breeding.

Fox activity

The Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group measures fox activity by collecting and weighing fox scats at mounds (fox scat weight).

More information on above charts - Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group Reports

Projects & Partnerships

Adaptive Management project

This project is being carried out by Drs Michael Bode, Cindy Hauser and Jose Lahoz‐Monfort at Melbourne University. They are developing a program that will make the best use of the ongoing flow of monitoring data to better manage Malleefowl. The project aims to learn about the effect of predator control on Malleefowl at about 40 Adaptive Management sites across Australia. About half of these sites will be managed (treatment sites), the other half won’t (control sites).

Malleefowl habitat linkage projects

- Berrook (approximately 36km northwest of Murrayville) - this project was finished in May 2016 with involvement of the Mallee CMA and Greening Australia. The project has resulted in the Murray Sunset National Park now being linked with a large block of state forest at Berrook by a corridor created across previous grazed and cleared cropping land.

- Baring (11km southwest of Patchewollock) - this project was completed in July 2017 by DELWP. Wyperfeld National Park is now linked with the Baring/Bronzewing State Forest.

Mapping nesting mounds

In 2016/17 Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) scan mapping was used by DELWP to identify and protect nesting mounds within the Little Desert National Park, the Nurcoung Flora Reserve and Mount Arapiles-Tooan State Park, including private land adjacent and in between these reserves and adjoining private land from prescribed burning activities by DELWP. The project has assisted land managers to gain a better idea of the habitats inhabited by Malleefowl in this large landscape, and particularly the response of Malleefowl to different stages of habitat recovery after fire. Contact: Belinda Cant ,DELWP.

References & Links

- Benshemesh, J. (2007). National Recovery Plan for Malleefowl. Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia.

- Benshemesh and Stokie (2012) Mallefowl Monitoring - Report to the Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group, Joe Benshemesh and Peter Stokie 22 March 2012.

- Benshemesh and Stokie (2017) Mallefowl MonitoringReport to VMRG by Joe Benshemesh and Peter Stokie, March 2017 Malleefowl Recovery Group Reports

- Campbell, A. J. 1884. Malleehens and their egg mounds. Vict. Nat. 1:124-129.

- Cowley, R. D., A. Heislers, and E. H. M. Ealey. 1969. Effects of fire on wildlife. Victoria's Resources 11:18-22.

- FFG (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List (FFG Threatened List, Victoria, June 2024)

- Garnett, S. T., and G. M. Crowley. 2000. The Action Plan for Australian Birds. Environment Australia, Canberra

- Mattingley, A. H. E. 1908. Thermometer bird or mallee fowl. Emu 8:53-61, 114-121.

- Tarr, H. E. 1965. The Mallee-fowl in Wyperfeld National Park. Austr. Bird Watcher 2:140-144.

- Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Action Statement No. 59 - Malleefowl pdf

More Information

- National Recovery Plan

- Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group

- National Malleefowl Recovery Team

- National Malleefowl Recovery Team Newsletters

Icons of the Mallee - Parks Victoria - more about the Malleefowl, threats and ecloogy.