Plains-wanderer

Plains-wandererPedionomus torquatus | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Pedionomidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Endangered (IUCN 2017) |

| Australia: | Critically Endangered (EPBC Act 1999) |

| Victoria: | Critically Endangered (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| New South Wales: | Endangered (NSWBC Act 2016) |

| Queensland: | Vulnerable (QNC Act 1992) |

| South Australia: | Endangered (NPW Act 1972) |

| Vic FFG: | Listed: Action Statement No. 66 |

| Species profiles | |

| Australia: | Atlas of Living Australia profile |

| EPBC Act: | SPRAT species profile |

| Victoria: | |

| Zoos Victoria Figthing Extinction profile |

The Plains-wanderer is a small, ground-dwelling bird resembling a quail in appearance. It has number of unique characteristics, marking it as a species of great scientific interest. An unusual occurrence in birds, females are polyandrous; abandoning a male to hatch and raise her clutch of eggs while she seeks out a new partner. In addition, they display reverse sexual dimorphism, where females are larger and more brightly coloured than males with the female displaying a chestnut breast and a black collar with white speckles.

The Plains-wanderer is the sole member of its taxonomic family Pedionomidae (AFD 2017). It is thought to be most closely related to a group of South American shorebirds, the Seed-snipe (Thinocorus species) (Sibley, Ahlquist & Monroe 1988). Its origins can be traced back over 60 million years, to when Australia was still part of the Gondwana supercontinent (Olsen & Steadman 1981).

The female Plains-wanderer has a distinct collar of black and white speckles. The female is taller than the male and can stand approximately 17-19cm, with an average weight of 72.4g (with no egg) and has a wing span of around 28-36cm. The smaller male only stands at 15-17cm and weighs an average of 54g.

For a small ground dwelling bird, the Plains-wanderer has relatively long legs which are straw yellow in colour, which is more vibrant in mature females. In flight these legs trail beyond the tip of the tail. The Plains-wanderer displays a slower wing beat than a quail and have a noticeable wing bar and broad pale trailing edge.

The life expectancy of wild Plains-wanderers is still unknown. In captivity they have been capable of surviving at least eight years.

Distribution

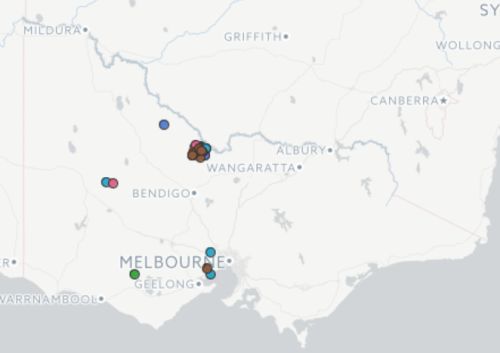

Historically, the Plains-wanderer’s distribution covered most of Australia’s south-east coast; ranging south from eastern Queensland, inland New South Wales, across most of Victoria and parts South Australia (National Recovery Plan 2016; Bennett 1983). Today, they are essentially extinct across much of their former range, with only three key areas remaining: the Riverina of south-western NSW, south-western Queensland and north-central Victoria.

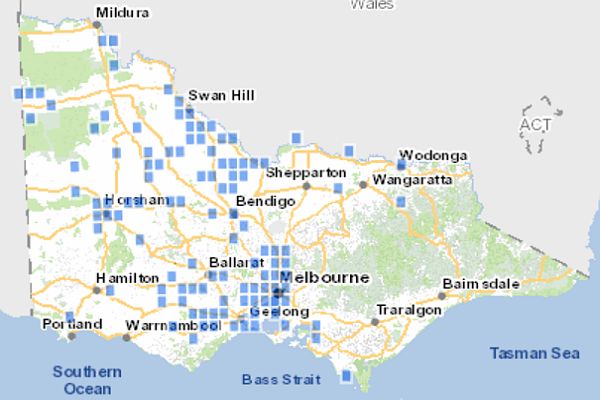

Records of Plains-wanderer in Victoria since year 2000. Source ALA 2017

Compared with the historic distribution this map illustrates a significant reduction in the Plains-wanderer ‘s range in Victoria.

The main Victorian population stronghold is now in the Campaspe area of north-central Victoria, particularly areas which surround Terrick Terrick National Park, Bael Bael Nature Conservation Reserve and Trust for Nature’s Wanderers Plain.

Other areas for consideration of Plains-wanderer are the Victorian Volcanic Plain and the Western Grassland Reserve immediately west of Melbourne.

Ecology & Habitat

As described by Baker-Gabb (1998), the preferred habitat of the Plains-wanderer consists of hard, red-brown soils with sparse native vegetation: a mosaic of grasses and herbs (40%), leaf litter (10%) and bare ground (50%). Grasses rarely exceeds 30cm in height, with the majority (94%) reaching less than 10cm, allowing for easy movement and foraging for seeds and ground-dwelling insects. However, some taller growth is essential for concealment from predators.

Low crops and cereal stubble occasionally offer temporary shelter, although this only lasts until the following cultivation (Baker-Gabb 1998; Bennett 1983). The Plains-wanderer also prefers areas where there are no trees or clusters of trees within 300m.

Breeding

Plains-wanderer (male) on nest.

Plains-wanderers can breed anytime of the year but generally favours spring and summer as their peak breeding seasons. The first clutches are laid mainly between August and early November, and then second clutches in January or later if summer rains fall.

After the female is mated and lays a clutch of eggs (3-5), it is the male who plays the primary role in incubation and is the sole caretaker of their chicks. Once chicks have hatches, the female could have already laid another clutch to a nearby male. Although the female is rarely seen on the eggs, the female does at times assist with incubation.

The father stays with the chicks for 8-12 weeks at which point the young disperse. Vocalisations are made by the male to call chicks, and chicks can be observed taking refuge under his apron.

Once chicks have hatched, the female could have already laid another clutch to a nearby male. Although the female is rarely seen on the eggs, the female does at times assist with incubation.

Movement

Plains-wanderers do not appear to be migratory or nomadic, although localised forced movements occur across the landscape due to agricultural practices like cultivation and inappropriate grazing regimes (Baker-Gabb 1998; Bennett 1983). One individual which was banded on the Northern Plains of Victoria was observed in a paddock 120km north of Deniliquin (NSW). This is the longest recorded movement of an individual of this species.

The Plains-wanderer is secretive and rarely flies, it can stand upright with its neck outstretched and will run for cover.

Feeding

The Plains-wanderer mostly forages for grass, saltbush seeds and insects during the daylight but can also be observed at night. Further details on feeding are contained in the National Recovery Plan.

Population Status

There has been a rapid and sever decline in the population.

The Plains-wander is a species which tends to responds to varying seasonal conditions, which in normal circumstance would mean the population increases during optimal seasons and decreased during droughts. The problem today is there have been so many changes to its natural habitat and reductions to its former range that populations have not been able to recover.

Overall, the Plains-wander has suffered a continual decline over many years but monitoring of remaining stronghold areas indicates a very rapid decline in recent years. In 2002 it was estimated there were 500 Plains-wanderers in Victoria’s Northern Plains Grasslands (DSE 2002). But monitoring and annual surveys, which have been conducted across the Patho Plains of Victoria since 2009, indicated a decline in numbers of approximately 95% between 2010 and 2012 (Baker-Gabb, Antos and Brown (2016).

The (National Recovery Plan 2016) estimates the Plains-wanderers population across Australia to be somewhere between 250 and 1000 birds, representing a record low for the species.

The National Environmental Science Program Threatened Species Research Hub (2019) estimated the population to be 500-1000 adult birds. Threatened Species Strategy Year 3 Scorecard – Plains-wanderer. Australian Government, Canberra.

More recent estimates using Song Meters to identify and count calls could mean the population could reach 2,000 birds, but this is subject to seasonal fluctuations. SWIFFT Seminar -26 October 2023, Plains-wanderer Using bioacoustics to monitor landscape-scale population dynamics of the critically endangered Plains-wanderer

Threats

The National Recovery Plan (2016) provides a detailed account of threats to the Plains-wanderer. In Victoria the main threats are:

Habitat loss – direct loss of native grasslands, fragmentation of remnant habitat, cultivation, cropping and increased woody vegetation in remnant grassland habitat.

Inappropriate habitat management – overgrazing during drought periods and under grazing during wet conditions can result in habitat decline.

Small population size – reduced capacity for genetic diversity, low breeding potential, magnified impact from drought and fire.

Feral predators – foxes and feral cats are capable of predating on Plains-wanderer, particularly as the Plains-wanderer is a ground nesting species.

Pesticide use – there is a potential threat depending on the type of chemicals and application rates being used. Further research is required to ascertain the impacts on Plains-wanderer through toxins being transferred through the food web.

Quail hunting – interaction between hunters and dogs has the potential to disturb or kill Plains-wanderers as being mistaken for quail.

Climate change – extremes environmental changes i.e. drought and high rainfall causing flooding pose a threat to the Plains-wanderer, particularly when a number of other threats are taken into account.

Conservation & Management

- Captive breeding - Werribee Open Range Zoo

- Trust for Nature and the Patho Plains

- Remnant Grassy Ecosystems – North Central CMA

- Parks Victoria

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

The National Recovery Plan (2016) is the main overarching document which provides detailed information regarding measures needed to ensure immediate and long-term conservation measures for the Plains-wanderer.

Objectives of the National Recovery Plan (2016)

- Reverse the long-term population trend of decline and increase the numbers of plains-wanderers to a level where there is a viable, wild breeding population, even in poor breeding years; and to

- Enhance the condition of habitat across the plains-wanderers’ range to maximise survival and reproductive success, and provide refugia during periods of extreme environmental fluctuation.

Conservation outcomes;

- 4000 ha of actively managed grasslands

- 1000 ha habitat with new conservation agreements

- Viable captive-breeding population across 3 institutes

- By 10 years there is an aim to be releasing 30-90 captive-bred individuals annually (NSW/Vic).

- By 20 years it is aimed that the captive breeding program is terminated as wild populations and habitat is secured.

Key partnerships in Victoria

The Victorian working group includes Zoos Victoria (Werribee Open Range Zoo), Parks Victoria, Trust for Nature, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, North Central Catchment Management Authority, Northern Plains Conservation Management Network and the local community.

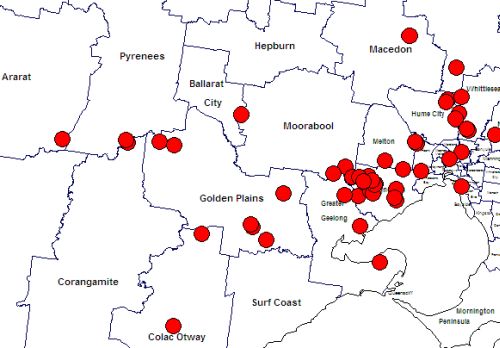

Key Local Government areas: Campaspe Shire, Loddon Shire.

Other known historic or occassional records of Plains-wanderer have occurred within Wyndham City, Gannawarra Shire, Buloke Shire, Horsham Rural City, Yarriambiack Shire, City of Greater Geelong, Melton City, Mildura Rural City, Swan Hill Rural City. Areas such as Maribyrnong City and Brimbank City have historic records (ALA 2017).

Zoos Victoria Fighting Extinction Program

The Plains-wanderer is one of the priority species in Zoos Victoria Fighting Extinction Program. The program involves establishing a captive population at Werribee Open Range Zoo (WORZ), one of several throughout Australia, to develop husbandry and breeding techniques as an insurance against extinction. The program also will help identify suitable release sites for captive-bred chicks to increase numbers in the wild.

Zoos Victoria involvement will help raise community awareness about the Plains-wanderer and its habitat requirements.

Captive husbandry is still in a research by trial phase. There have been numerous successful breeding’s reported from private aviculturists but none in recent times and details are sketchy. As of April 2017, Taronga and Featherdale have been the only recent properties to hold captive PWs

The captive breeding facility at WORZ is expected to commence in mid-November 2017. It will have 22 pens of two different sizes. Each enclosure is equipped with cameras, heaters, water, misters and feed chute. The WORZ team will also be trialling slightly different vegetation amounts to see if there is a preference between more or less vegetation. The program will be very hands-off and observations will mostly take place via these cameras.

Camera footage will provide an insight into the birds behaviours and lifestyles, which still has many unknowns. A song metre will also be used to gather information for a Plains-wanderer vocalisation data-base. DNA from all birds entering the collection will be sent off for genetic analysis.

Zoos Victoria is also looking to see if training the dogs in identifying a Plains-wanderer (detector dogs) can be beneficial in monitoring and locating birds in the field.

Zoos Victoria - Plains-wanderer captive breeding project.

Trust for Nature and the Patho Plains

Since the early 1990s Trust for Nature (Victoria) (TfN) in partnership with State and Federal government agencies and local land owners have been working to protect, restore and improve the condition and extent of Grasslands in the Victorian Riverina

These additions have resulted in Terrick Terrick National Park now covering over 3334ha and the establishment of Bael Bael Grasslands NCR during 2010 and 2011 which now covers 3119ha.

Private land under conservation covenant as well as Trust for Nature establishing a number of reserves to build its private reserve network in the Victorian Riverina. These efforts have resulted in the addition of 2804ha owned by Trust for Nature, including Glassons Grassland Reserve (2001), Kinypanial (1999), Korrak Korrak (2001), Wanderers Plain (2009-2010) and 1036ha of private land protected under conservation covenant.

The protected Area Network in the Victorian Riverine Plains has grown from virtually nothing in the mid-1990s, to in excess of 10,000ha and continues to expand.

North Central Catchment Management Authority

Conservation of Plains-wanderer is carried out under the Remnant Grassy Ecosystems project which aims to support landowners to protect native vegetation and improve habitat condition on their property.

The project targets regional hotspots of grasslands, grassy woodlands and seasonally herbaceous wetlands – all nationally endangered vegetation communities. A big focus of the project is securing important conservation covenants on the Patho Plains.

In partnership with Trust for Nature and with funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programm, one of the aims of the CMA’s Remnant Grassy Ecosystems project in the northern part of the catchment is to help extend and preserve Plains-wanderer habitat.

There are three priority target areas - Patho Plains, Lower Avoca Grasslands and Bunguluke. The aim is to;

- improve the condition of 10,000 ha of grassy ecosystems through an adaptive management program.

- protect and enhance an additional 1,000 ha of grassy ecosystems through conservation covenants and a targeted incentive program, reduce threats of rabbits and foxes over at least 2,500 ha through a threat abatement program and engage Traditional Owners in, and increase their capacity for, grassy ecosystem management.

North Central CMA – Remnant Grassy Ecosystems

Parks Victoria

Parks Victoria partners with Trust for Nature, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and adjoining private landholders undertakes a range of works in the Northern Plains Grasslands, including Terrick Terrick National Park and and Bael Bael Grassland Nature Conservation Reserve.

On-ground works include strategic weed control, rabbit control and predator control. Plains-wanderer grassland habitat is monitored with active management of grazing to maintain habitat. Ecological grazing has been carried out at two key reserves in north-central Victoria, Terrick Terrick National Park and Bael Bael Grassland Nature Conservation Reserve. Fauna monitoring and fencing is also carried out as part of the program.

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, Victoria

In June 2017 a $300,000 biodiversity on-ground action initiative was directed to Plains-wanderer conservation. This will be of great assistance in undertaking urgent conservation activities by project partners.

DEECA works in with other agencies in relation to the use of Song Meters which provide a recording of calls from which the Plains Wanderer can be identified. The Plains Wanderer call is a distinct low frequency sound which can be identified by software.

Plains-wanderer as a flagship species

A study in Victoria’s Northern Plains in 2011 found the Plains-wanderer can fulfil its role as a local flagship species, without addressing the traditional criteria of being a large, internationally renowned species. As a flagship, the Plains-wanderer has stimulated conservation concerns beyond its own protection by raising awareness and concern for its grassland ecosystem and interest in residents in learning about other grassland species. The case study of the Plains-wanderer successfully promoting a threatened ecosystem highlights the opportunity for adaptive management strategies to promote conservation on a community-based level and landscape-wide scale through the aid of local flagship criteria (Johnstone 2011).

Grassland Conservation and the Plains-wanderer: A Small Brown Bird Makes an Effective Local Flagship Johnstone, K., Miller, K., Antos, M. Conservation & Society, Vol. 13, No. 4 (2015), pp. 407-413

Native grasslands as a farming asset

As discussed by Barlow (1998), landholders can gain a number of benefits by maintaining native grasslands on their property: Native grasses are drought resistant and tolerant of low nutrient, acidic and saline soils and can indicate changes in both salinity and the water table levels. As most are perennial grasses, they provide annual and emergency fodder for stock. Native grasslands also provide vital Plains-wanderer habitat.

References & Links

- AFD (2017) Australian Faunal Directory, Species Pedionomus torquatus Gould, 1840 https://biodiversity.org.au/afd/taxa/Pedionomus_torquatus

- ALA (2017) Atlas of Living Australia. https://www.ala.org.au/

- Baker-Gabb, D. J. (1988). The diet and foraging behaviour of the Plains-wanderer ''Pedionomus torquatus''. Emu 88, 115-118;

- Baker-Gabb. D. J. (1998). Native Grasslands and the Plains-wanderer. Wingspan. Birds Australia Conservation Statement No.11 (previously No.1). Birds Australia, Australia.

- Baker-Gabb, D., Antos, M. and Brown, G. (2016) Recent decline of the critically endangered Plains-wanderer (Pedionomus torquatus), and the application of a simple method for assessing its cause: major changes in grassland structure. Ecological Management & Restoration 17(3): 235-242 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/emr.12221

- Barlow, T. (1998). Grassy Guidelines: How to manage grasslands and grassy woodlands on your property. Trust for Nature, Melbourne;

- Bennett, S. (1983). A review of the distribution, status and biology of the Plains-wanderer ''Pedionomus torquatus'', Gould. Emu 83, 1-11.

- Bowen-Jones, E., and Entwistle, A. (2002). Identifying appropriate flagship species: the importance of culture and local contexts Oryx 36, 2, 189-195.

- DSE (2009) Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria – 2009, Department of Sustainability & Environment East Melbourne, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, Victoria.

-

FFG Threatened List (2024), Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

-

FFG Act (1988) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, Action Statement, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

- IUNC (2022) BirdLife International. 2022. Pedionomus torquatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T22693049A212570062. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T22693049A212570062.en. Accessed on 10 October 2024.

- Johnstone (2011) Utilising local species as flagships for conservation, Kyla Johnstone Deakin University Thesis 2011.

- Maher, P. N,. and Baker-Gabb, D. J. (1993). Surveys and Conservation of the Plains-wanderer in Northern Victoria. ARI Technical Report No. 132. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Melbourne.

- National Recovery Plan (2016) Plains-wanderer (Pedionomus torquatus), Australian Government.

- NSWBC Act (2016) New South Wales Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Fact sheet: Plains Wanderer pdf

- Olsen & Steadman (1981) The relationships of the Pedionomidae (Aves, Charadriiformes, Book, Volume 337, Smithsonian Institution Press (Washington).

- QNC Act (1992) Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992; Plains-wanderer listed in Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006

- Sibley, Ahlquist & Monroe (1988) A Classification of the Living Birds of the World Based on Dna-Dna Hybridization Studies, The Auk, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Jul., 1988), pp. 409-423, Published by: University of California Press.

- VBA (2024) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria.

SWIFFT Seminar -26 October 2023, Plains-wanderer Using bioacoustics to monitor landscape-scale population dynamics of the critically endangered Plains-wanderer

Water-based, non-toxic, solvent free pigment ink on linen fabric, linen thread, stainless steel 76 x 49 x 6.5 cm. By Jane Burns

This art work depicts the precarious state of the Plains Wanderer. Will this critically endangered species continue to disappear?