Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo

South-eastern Red-tailed Black-CockatooCalyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Cacatuidae |

| Status | |

| Australia: | Endangered EPBC Act |

| Victoria: | Endangered (DEECA 2024) |

| FFG: | Listed; Action statement No. 37 |

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos Male (rear) and female (perched);

note barring on tail.

The Red-tailed Black-CockatooCalyptorhynchus banksii is a large dark grey-black cockatoo up to 63cm in length. Its genus name Calyptorhynchus is derived from the Greek words calyptos - hidden - and rhynchus - beak.

It has a rounded crest and a large bill; males have a dark bill and an obvious red tail band whilst females have fine yellow spots on the head and wings with yellow barring across the breast. Females also have a more yellow-orange-red barred tail band and a creamy coloured bill. Juveniles have similar markings to females and a duskier coloured bill.

Five distinct subspecies are recognised in Australia, with considerable variations in overall size, bill shape, bill size and colour between each of the races.

Calyptorhynchus banksii subspecies

-

Calyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne - south-west Victoria and south-east of South Australia (referred to as the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo).

-

Calyptorhynchus banksii banksii - northern and eastern Queensland.

-

Calyptorhynchus banksii macrorhynchus - northern Western Australia, Northern Territory and Gulf of Carpentaria.

-

Calyptorhynchus banksii samueli - Inland Australia from western side of Western Australia, Central Australia and patchy through the Murray-Darling area in western New South Wales.

-

Calyptorhynchus banksii naso - south-west corner of Western Australia.

Calyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne is smaller in overall body size than other subspecies. It also has the lowest population and is restricted to the south-west of Victoria and adjacent areas in the south-east of South Australia. The population in 1996 was estimated to be not more than 1000 with only a small proportion (10%) or 100 breeding pairs (Emison 1996), In 2002 the highest count was 785 birds (Commonwealth of Aust. 2007). In 2015 the population was estimated to be around 1500 individuals. The 2016 count was 901 birds. Monitoring of flock counts in 2016 also found that either no young from the past three years have survived to join flocks or that there has been an increase in the death rates of adult females (Red-tail newsletter Issue 43 November 2016). Monitoring of flocks in 2017 found an increase in the number of barred birds compared with 2016 which indicates there could have been some successful nesting the previous year but in the 2018 the numbers of barred birds were down indicating there has been very little successful breeding over the past three years.

Distribution

Source: Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, January 2024.

Ecology & Habitat

The south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo inhabits Brown Stringybark Eucalyptus baxteri woodlands (Heathy Woodland EVC) as well as River Red Gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Yellow Gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon, Swamp Gum Eucalyptus ovata, Buloke Allocasuarina luehmannii, Drooping Sheaoak Allocasuarina verticillata and occasional patches of Pink Gum Eucalyptus fasciculosa.

Different habitats are used for feeding, nesting and roosting; feeding areas of Heathy Woodland EVC are mostly within state forests and parks reserves whilst Buloke feeding areas and nesting habitat with Red Gum associated EVCs are predominantly on private land (Joseph 1991, Venn 1993, RFA 2000, Maron 2005). Approximately 68% of roosting habitat is located on private land with Red Gums being the most utilised trees (Commonwealth of Australia 2005).

Feeding

Diet of the south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo is specialised, consisting of seeds from the Brown Stringybark Eucalyptus baxteri as the primary source of food. During late summer or early autumn seeds from Bulokes Allocasuarina luehmannii become an important source of highly nutritious food.

Understorey communities can substantially influence habitat productivity. Stringybark communities dominated by large grass-trees (Xanthorrhoea australis) have substantially lower capsule density, while communities dominated by bracken have substantially higher capsule density (RTRBC Issue 48 April 2019).

Buloke trees in paddocks in the southern Wimmera have been identified as providing critical feeding habitat in this area (Maron 2005) and Buloke dominated woodlands of this region are nationally endangered under the EPBC Act 1999 (DEH 2000). Buloke seed is only available during January to March and the Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo only forages in large mature trees greater than 19cm dbh (diameter at breast height) which are estimated between 100 years to 200 years old. They prefer trees over 200 years old (Maron and Lill 2004). Different trees are used in different years with the most valuable trees being large, with large cone crops and close to other Bulokes (Loyn et al. 2007).

A pair of Red-tailed Black-cockatoos feeding in a Buloke tree. (male left; female right) note barring on the females tail feathers. Image courtesy Sky McPherson, RTBC Recovery Team.

Nesting

The south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo uses large hollows (15-50 cm) which occur mostly in very old, large eucalypts. A six year study of nesting between 1988-1994 found a low incidence of nesting with only 16 nests being the highest number recorded in any one year. Nesting has only been recorded in the northern half of the range. Hollows in River Red Gums Eucalyptus camaldulensis provide the most favoured habitat for nesting, with 90% of recorded nest sites being located on private farmland. Of these 85% were found in dead, usually ring barked, trees (Emison 1996).

Nests are more likely to be close to the cockatoo’s stringybark feeding habitat which can change from year to year which also explains why it is uncommon for pairs to use the same nest each year as they move about their range in search of food and new nest hollows.

Although Red-tails can return to the same breeding areas in different years and in some cases even return to nest in the same paddock, they don’t necessarily use the same tree.

Tree hollows are needed for Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo nesting

Female Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo feeding young. Footage: courtesy Bob McPherson.

Threats

A shortage of food sources has been identified as the main threat to the survival of the south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo with associations between the amount of seed production and nesting success (Commonwealth of Aust. 2005).

Loss of paddock trees

Loss of Buloke feeding trees

Natural senescence and the intensification of agricultural practices are contributing to the continuing loss of paddock trees in the southern Wimmera area where much of the Buloke woodland vegetation community is now only represented by relict Buloke trees in paddocks. A study into the rate of loss of Buloke trees has found less than 2% of this important food species remains. Over the past 15 years in the southern Wimmera there has been a 25.8% loss with three times as many trees being removed for centre pivot irrigation. There has been a 63 % decline of Bulokes in cropping areas and a 32 % decline in grazing areas.Further, it has been estimated that only 35% of the 1981/82 count of Bulokes will remain by 2020 and that it could takes up to 100 years to replace feeding trees. In the meantime there is going to be a prolonged period with extremely low Buloke feeding habitat (Maron 2005).

Loss of Stringybark feeding trees

About 54% of the Strinybark food resource has been cleared and now mainly exists in Public Land. Significant seed resources are still present in scattered trees on private land, the number of trees may be significantly reduced but the remaining trees have high seed crops making them a valuable feeding resource. Unfortunately old large paddock trees are not being replaced at high enough rate to cater for RTBC feeding needs into the future.

A failure of recruitment of this species across landscapes where the RTBC occurs has been raised as a major issue. Stringybarks are not well represented in National Parks, they are mostly found on Crown Land or State Forest and are frequently targeted for burning which is a problem, if burns are too hot there is simply no germination which results in a lack of age diversity. It can take 15-20 years for a canopy to recover.

In revegetation areas where direct seeding is used there has been good germination but the trees do not make it past the first summer. Low soil moisture and high soil temperatures being identified as the main reasons for loss. During Winter, fungal damage and frost damage have resulted in poor survival of seedlings. Overall the Summer and Winter issues are related to lack of canopy protection.

A study of habitat loss between 2004-2017 found rates of loss for paddock trees have substantially increased across all major habitat types. Paddock tree cover loss for gums (mostly Red Gums) averaged around 2.4% per annum with drought stress and dieback being considered the most important factors (Red-tail, Issue 50, April 2020).

If the rate of paddock tree loss continues, all the mature gum paddock trees in the Red-tail’s range will be gone within 42 years (Red-tail, Issue 50, April 2020).

Fuel reduction burning

Fuel reduction burning in state forest and park reserves can impact on seed production in Brown Stringybark forests. Excessively hot fires can reduce fruit production for up to nine years, which can limit the availability of food. (Venn 1993, Commonwealth of Aust. 2005). Burning of stubble can result in loss of Buloke feeding trees (Maron 2005) and loss of dead Red Gums, which provide nesting habitat.

Wildfire

Wildfire can have major impacts on recovery of woodland communities utilised by the south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo. Red Gum and Yellow Gum do not respond well to burning, particularly as dead trees which provide nesting opportunities can be lost. When fires are intense enough to cause crown scorch in Stringybark feeding habitat, food production is reduced for an average of 10 years. This is a major threat to this food-limited species.

Loss of tree hollows

The loss of nesting trees since 1947 has been dramatic. There has been a 39% loss on grazing landscapes and a 49% loss on in cropping areas, a 53% loss in Pivot irrigation and 69% loss in Plantation areas.

Large hollows tend only to form in the old large diameter trees. The smallest diameter trees used for nesting are 60cm, with the average nesting trees 100 cm dia. About 90 % of the former large nesting trees have been lost, this has occurred mainly on Public Land. The remaining old large suitable nesting trees are mainly on private land but there is minimal regeneration of scattered trees on private land, therefore the nesting resource will continue to decline.

Illegal birding

The collection of eggs and chicks for the illegal bird trade is of concern, particularly as nest sites become targeted by thieves and around the clock monitoring is difficult. Members of the public are encouraged to report people who may be unlawfully keeping and trading Red-tailed Black-cockatoos or people behaving suspiciously at or near key habitat locations; call DELWP’s Customer Call Centre on 136 186.

Conservation & Management

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo chick in artificial PVC hollow which is the first time successful nesting has been recorded in this type of hollow.

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo advanced chick in supplementary hollow made from a natural wood hollow.

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo fledgling in a supplementary natural wood hollow nest attached to a pole.

Funding for the continuation of the Redtail recovery program beyond 2025 has been made possible through the National Heritage Trust. The funding will be delivered by the Limestone Coast Landscape Board, Wimmera Catchment Management Authority and Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management

Authority, members of the Regional Delivery Partners panel working in partnership with the recovery team and Birdlife Australia.

Previous conservation measures

Trials of supplementary nest hollows on poles and in dead trees have proven worthwhile. Trials in 1993-1994 found there was a high uptake, which accounted for 45% of total south-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo nests in that year (Emison 1996).

Implementation of an Environmental Significance Overlay (ESO) Red-tailed Black Cockatoo overlay within the Glenelg Shire and West Wimmera Shire Planning Schemes. These planning overlays require a permit to remove any dead eucalypts (or River Red Gums in the case of Glenelg Shire) with a diameter greater than 60cm at 1 metre above ground level.

Fuel reduction management guidelines in Horsham and Portland Forest Management Areas to maintain 85% of Stringybarks that have not experienced a crown-scorch fire event for at least 10 years. Assessments are carried out to identify areas which need to be deferred from fuel reduction burning where they contain prime stringybark seed feeding habitat.

The present Recovery Plan was prepared in 2007 and has 17 actions. Birdlife Australia and recovery team partners have been working on a new draft plan in 2021.

Research

Annual counts and flock counts

1. Determine the minimum number known to be alive and to gain an insight into previous seasons breeding success.

Birdlife Australia with the help of volunteers conducts an annual count (usually April/May).

2. Investigate how this data may be used in a long-term analysis of population trends.

2013 Annual count, 1118 birds (excluding double counts) were counted in Stringybark forest across the species range in South East of SA and South West Victoria in May.

2013 Annual count was down by 350 birds on the 2012 count of 1468 birds but it is likely that birds were just missed on the day, rather than the population suffering a significant decline over the last year.

2015 Annual count, 1545 birds (excluding double counts). This count was held in May and had 77 more birds than the previous best tally of 1468 recorded back in 2012.

2016 Annual count, 901 birds (excluding double counts) which is a decline since the previous year's count of 1545 birds.

2017 Annual count on 6 May 2017, 810 Red-tails were counted across south-western Victoria and the South East of South Australia. The count was lower than previous years but it is unlikely that the population has suffered a significant decline over the last 12 months.

2018 Annual count on 4 May 2018, 839 Red-tails were counted, which is slightly more than the 810 birds recorded last year. More than 175 volunteers participated in the annual count.

2019 Annual Count on 4th May 2019, 1193 Red-tails were counted which is substantially higher than last year’s total of 839 birds. However, it is unlikely that the population has increased over the past year, it is likely that more birds were counted on the day due to the improved weather conditions. More than 170 volunteers took part in this year’s count.

It is important to note that fluctuations in annual counts will occur as birds may be more dispersed or concentrated across their range from one year to the next. The critically small population is believed to be still in decline based on the ongoing loss and deterioration of the species’ key habitats.

In order to better refine the flock count methodology the project team developed a new survey protocol in 2015/16 which clearly describes the manner in which flock counts are to be conducted.

2020 Annual count - on 2nd May, the normal scheduled count was cancelled due to Covid-19 but a modified count was undertaken by people on their own properties and backyards. The team received 18 sighting reports with a total number of 748 Red-tails. Taking into account sighting reports received in the week before and after the event, as well as several large flocks which were known but weren’t counted on the day, the number of birds counted came to 1,144.

2021 Annual count - on 1st May 2021, 1230 birds with 57 distinct sightings which is a strong increase from the 2019 result of 43 sightings. Six large flocks ranging in size from 80-200 birds were included with in the total. 181 volunteers spent over 340 hours searching for Red-tails across their range.

2022 Annual count - conducted on 7 May 2022 with 118 volunteers. The final count being 1,143 birds mainly comprised of 5 large flocks ranging in size from 70-250 birds. Birds were located in the areas of Edenhope, Coonawarra and Rennick. Other sightings were made near Benayeo, Charam, Langkoop, Dergholm, Penola, Francis and Wandilo.

2023 Annual count - conducted in May 2023 with 128 volunteers. The final count being 1,204 birds.

2024 Annual count - conducted 4 May 2024 with 80 groups totalling 177 volunteers. The final count being 1,303 birds, Volunteers covered 3,342 kms of stringybark forest tracks and roadsides looking for the elusive cockatoos. A total of 58 sightings were made on the day, however 24 of those were considered double counts of the same birds and excluded from the final tally. An additional 8 sightings tallying 364 birds, collected either side of count day were included in the result.

2025 Annual count - held on 3 May 2025 with 84 groups totalling 205 volunteers. Final count of 885 birds. The lower count is thought to be a reflection of wider than usual dispersion of flocks rather than a drop in the population.

Flock counts

3. Analyse flock count data and compare results with food availability information.

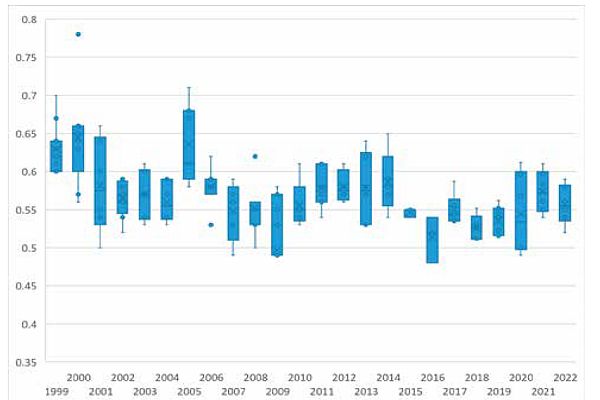

Flock counts are carried out in in autumn each year following the annual count. Flock counts provide the best indication of breeding success by counting adult males and barred birds (Barred birds represent all adult females and young less than four years old). The more barred birds counted year on year indicates successful breeding taking place.

Year 7 of a 10 year study has found a definite link between breeding success and food availability. Red-tails are absolutely dependant on the fruit from the two types of local stringybarks (Desert and Brown Stringybark). Red-tails also eat from Bulokes but Stringybarks provide year round food (Bulokes only have seed available for a couple of months a year).

Monitoring of seed crop revealed that in the breeding season of 2015 there were basically no new seed crops on Stringybark trees at any of the monitoring sites across the Red-tail range. In seven years of detailed monitoring of Stringybark seed production the recovery team has never seen a year with so little food for Red-tails.

2016 flock counts found that either no young from the past three years have survived to join flocks or that there has been an increase in the death rates of adult females.

2017, six flocks totalling 633 birds were counted which had 55% barred birds (a higher proportion of barred birds than 2016 with 51%). This indicates there could have been some successful nesting in the previous year. The average since 1999, 19 years of counts, is 58% barred birds.

2018, flock counts have revealed a disturbing trend with declining numbers of females and juveniles recorded in flocks over time. In the past three years the researchers have seen very poor results with this year only 53% of flocks being barred birds. Thus, it appears there has been very little successful breeding over the past three years.

2019, six flocks were counted totalling 527 birds, of which 54% were barred birds. This is slightly higher than last year’s result although this difference is unlikely to be significant. This year’s results continue the trend in lower mean proportion of barred birds in flocks which has been ongoing since 2015, indicating that the SERTBC population is continuing to decline.

2020, the count involved six sites totalling almost 800 birds. Birds were counted near Wilkin, Apsley, Ullswater, Frances, Harrow and Lucindale. The mean proportion of barred birds was 54%. The proportion of barred birds in flocks over the past six years is consistently below the long-term average and confirms a trend for fewer young birds or adult females that has been observed over the past six years.

Food monitoring suggested that Desert Stringybark food availability was the highest since 2013.

2021, the count was conducted over six sites totalling 522 birds of which 57% were barred. About two-thirds of birds were recorded in Desert Stringybark, the other third in Brown Stringybark. The number of barred birds recorded is the highest in the last few years. The widespread increase in barred birds indicates more young birds in the flocks due to a good breeding season in 2019/20. The successful breeding season also coincides with a noted increase in the abundance of high quality stringybark seed in 2019/2020.

There are signs that seed productivity for the 2021/22 season will be high which may again produce successful breeding in 2022.

2022, the count comprised 6 flocks totalling 535 birds. The average proportion of barred birds was greater than any values observed since 2014 which could be due to a successful breeding season in 2021/22. It is thought the higher proportion of barred birds can be explained by continuing levels of relatively higher food availability in stringybarks. Although a good year for 2022, when taken over a 10 year timeframe there has still been a decline in new recruitment to the population.

Flock count proportion of barred birds in flocks. Source: Red-tailed Black Cockatoo Newsletter No. 55 November 2022.

2024, the flock count was carried out at six sites totalling 512 birds. Two flocks of birds were counted west of Penola, one near Casterton, two near Dergholm and one north of Edenhope. Across those flocks 57% of birds were barred which is only slightly lower than the long-term average of 58% barred birds.

Population Viability Analysis (PVA)

Population Viability Analysis (PVA) for the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo has been carried out by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. This work found that changing food availability can influence juvenile mortality and the trajectory of the population, and that fire (through its impact on food availability) can markedly affect population performance. Extinction rates are significantly higher under a 5% burning scenario (5% habitat burnt per year - as representative of more recent levels of burning) compared to that of more historical rates (1.5% habitat burnt per year). The study reinforces the need to maintain a burning regime which ensures no more than 15% of South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo stringybark habitat is burnt in a 10-year period. Any increase in canopy scorch beyond the historical average of 15% is likely to significantly impact the population.

http://www.redtail.com.au/fire-management.html

Nest incentive scheme

Undertake surveys to locate and protect nest trees. The Nest Incentive Scheme has been set up to encourage reporting of nests. Between 2011 to 2022 the nest incentive project has proved to be a great success with more than 40 new nests found across 11 sites. New nests have been found near Benayeo, Casterton, Powers Creek, Edenhope, Dry Creek and Naracoorte. Many of the ‘new’ nests found have been re-used by Red-tails again in subsequent years.

A highlight was the 2016/17 season when 9 new nests were found in the Casterton and Edenhope areas.

No new nests were discovered in in 2019.

The Nest Incentive Scheme is continuing across the range of the cockatoo for the 2022/23 breeding season (September to March). Anyone who observes nesting behaviour is encouraged to report their observations to the Project Coordinator on 1800 262 062 or by email redtail@birdlife.org.au

Stringybark seed crop assessments

Identify and protect prime Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo feeding habitat. In 2012, DSE carried out surveys of Stringybark forests to identify important feeding habitat in areas planned for fuel reduction burns. In the Far South West Fire District 34 planned burns totalling 12,041 ha with 8,094 ha of stringybark were assessed for seed crop. Four of the planned burns, 767 ha in total with 511 ha of stringybark were deferred because of the high seed crop which can provide prime feeding habitat.

In the Wimmera Fire District 25 planned burns were assessed (11,130 ha) with 4 planned burns (1,268 ha) deferred due to high seed loads in brown and desert stringy bark.

Seed crop 2017

Annual stringybark monitoring indicated that availability of new seed crops had increased substantially between 2015 (also at a record low) and 2016, and that birds breeding in 2016 would have access to some new seed crops as a result. The 2017 stringybark monitoring suggests that breeding success should be higher in 2017.

Buloke seeding

Monitor Buloke seeding - Buloke trees provide a food source from January to March. It has been observed that the Buloke seed crop in 2014 & 2015 has been reduced possibly due to lack of rainfall. Seeding was finished by the end of February.

Seed Crop 2019

Annual stringybark monitoring from 2019 showed that food availability in stringybark was lower this past 12 months than the previous year, and is at the lower end of levels recorded since 2007. A large flowering event was observed in February occurring in Desert Stringybark (Eucalyptus arenacea) in the northern range of the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo. Maturing capsules from this event will become available in late spring 2019, and be detected in next year’s capsule monitoring.

Seed Crop 2020 - 2021

There was a high seed production in Desert Stringybark in 2019/20. Seed production in Brown Stringybark was also up, the highest measured since 2012.

Seed Crop 2021 - 2022

A significant loss of Red-tail habitat occurred in December 2021/January 2022 at Poolaijelo on the Victorian / South Australian border due to a bushfire which burnt over 7,000 hectares, including part of the Meereek State Forest.

Seed Crop 2024

Results from the past four years of stringybark food monitoring suggest that food availability has also been relatively high based on long-term averages.

Seed Crop 2025

There are indications that dry conditions are having an impact on food production with surveys finding low capsule density scores in stringybark forests across the red-tails’ range. Wildfires in 2025 have also impacted on the availability of food in some areas.

Bioacoustics PhD

2016, Daniella Teixeira, PhD Student, University of Queensland PhD commenced research into the application of bioacoustics (combines studies in biology and sound) for conservation commenced to develop and implement bioacoustics techniques to improve the nest monitoring of Red-tailed Black-cockatoos.

The most important sounds for monitoring are those that the nestlings make. Nestling calls are unique and, in the second half of the nesting period, are heard just about every day which is good for confirming nest activity.

2016 to 2019 the project has involved monitoring of 24 nests using remote sound recorders.

During the 2016-17 peak breeding season, 9 nests were monitored. Once breeding-related calling behaviour is understood, bioacoustic methods can be tested in the field, to investigate important questions about breeding location, nest survival rates, hunger, and the relationship to feeding habitat.

2017/18 the bioacoustics project continued in with 14 nests being monitored. Several nests were monitored right through to fledging which greatly assist in developing bioacoustic methods for nest monitoring. Over the two breeding seasons it was found that 37.5% of chicks survived to fledging which is comparable to other cockatoo species.

The reasons for nest failure are not completely understood but it was noted that the failed nests were abandoned early in the season – either at the egg stage or soon after hatching. Possible reasons might include unfertilised eggs, poor genetic quality, or insufficient access to food.

2018/19 analysis of recordings from the breeding season in November 2019 found that at least 15 Red-tail pairs were using the natural and artificial nests. The bioacoustics monitoring will also help in identifying how many chicks fledged from these nests.

2019/20 in February 2020, 40 Red-tail nest boxes were installed across the Redtail’s range which brings the total number of new boxes to 65.

Sound recorders were used to monitor breeding at 36 Red-tail nests. This included 25 new artificial nest hollows in the Wimmera region (potential nests), and 11 nests where breeding had commenced (active nests). The project found 13 nests were active. Nestlings were recorded at nine nests, or 69% of active nests. Nest survival among active nests was between 23 – 38%, and it may be higher if some nests of unknown outcome were successful. Of the nests whose outcome was known, 43% fledged.

2020/21 - sound recorders were used to monitor breeding at 89 Red-tail nests the Wimmera, Glenelg Hopkins and South East SA regions. 55 nests were inactive due to the nomadic nature of the cockatoo. Results from the recordings estimate that 11 – 56% of nests survived to fledging.

Four artificial hollow nests were monitored in the Wimmera, 2 of the nests were used the previous year and 2 were used for the first time.

2021/22 - In addition to existing acoustic monitoring at nest sites, a University of Melbourne, masters of biosciences research project commence in 2021 by Oliver Wardle in collaboration with the Dept of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) and Birdlife Australia to implement one of the largest audio monitoring efforts to date. The research follows on from previous acoustic research but aimed at studying the connection between attributes of the landscape, habitat disturbances and breeding success rates.

2023/24 - sound recorders were deployed at 120 nest sites, including natural nesting hollows and artificial nests. At 74 newly monitored sites, 14 showed confirmed use by Red-tails. A total of 33 active nests were identified, equating to about 28% of the monitored hollows with 16 nests producing fledglings. Artificial nests produced at least one fledgling from 11 out of the 14 monitored nests.

A sound recorder in a waterproof box installed on a tree, protected by a tree collar. Image: Kelsey Bennett

More in (Red-tail, Issue 50, April 2020).

Updates are regularly posted on Instagram @ blackcockatooproject and facebook Black-Cockatoo Project.

Nest box trial - 2018 nesting season

In order to maximise the potential of artificial nest boxes the Red-tail team will test three different aspects of nest boxes:

- Width of the nest box: (a larger 370 mm and the currently used 300 mm internal diameter culvert 1200mm long.).

- Placement height: at a height which Red-tails are known use, and at a lower height which would allow easy maintenance.

- Tree type: boxes placed in both live and dead trees to see if there is a preference.

Surveillance cameras were used to monitor the nest boxes constantly over the nesting season providing valuable information into how different animals use nest boxes.

Results suggest continuing with the use of the smaller 300 mm dia. nest boxes may be preferable as the larger diameter boxes may be more attractive to competitor cockatoo species. The Eurasian Starling was the most common visitor to the nest boxes but they don't actually use the boxes for nesting. The main nest box competitor species are Crimson Rosellas and Maned Ducks which tend to have a preference for dead trees.

However, as SERTBC may actually select dead trees for nesting sites it is recommend that nest boxes be installed in both tree types. With monitoring of nest boxes using bioaccousitc recorders it is hoped a better understanding of tree selection will become clearer over time.

Volunteers required for stringybark seed monitoring

The Recovery Team needs more information about the availability of stringybark seed for Red-tails across its range. This information will help the Team learn more about how and where lack of food is contributing to the decline of our treasured Red-tails.

The Recovery Team has developed an app that volunteers can download onto their phone.

Volunteers can use the app to collect important information about stringybark trees including canopy and seed capsule volume across the Red-tail’s range.

The Team is hoping to have volunteers monitoring across the whole range of the Red-tail over successive years so an understanding of the full picture can be obtained.

To register contact Kelsey 1800 262 062 or redtail@birdlife.org.au

Buloke cone production monitoring – help required

Cone production has been monitored since 2019 at 50 sites and 250 trees. Cones are found on the female Buloke trees after Christmas through to the end of February. The cones only remain on the trees for a few months, but during that time they are often the first food of choice for Red-tails.

Over the four years of monitoring, it has been found that in 2019 and 2021 there was virtually no cone production whilst 2020 and 2022 had good cone production.

Understanding the occurrence and annual changes in Buloke cone production is important in determining how this influences the movement and breeding success of Red-tails.

If you would like to assist in next year’s Buloke monitoring, please contact Richard Hill

Stringybark blooming and capsule production study - photos required

Researchers from Melbourne University are seeking assistance from people in the Red-tail’s range by providing images of either Brown or Desert Stringybark trees showing flowers, buds, and/or capsules, including date and place. Contact: stringybarks@gmail.com

Projects & Partnerships

Education

‘Kids Helping Cockies’ project

This project involves working with local schools and students to grow and plant out stringybark food trees for Red-tails across the range of the cockatoo in South Australia.

The program, which started in 2012, has resulted in presentations to over 2900 students from 32 schools about Red-tails and the establishment of nine ongoing school nursery programs to grow and plant out stringybark seedlings for localised habitat revegetation projects for the cockatoo.

In 2019, nine schools involving 337 students helped to plant 1337 seedlings including a mix of stringybark and associated understory species across seven sites.

In 2020, 400 students were involved in the program across eight schools in south-east SA. Approximately 1750 stringybark seedlings were propagated for future plantings aimed at local habitat restoration. A further 916 seedlings including a mix of stringybark and associated understory species were planted by students involved in the program across seven sites.

In 2020-21, a total of 541 students were involved in 42 Kids Helping Cockies activities. A further 62 teachers and parent helpers were also involved, bringing the total number of regional participants in the program to 603. Seedlings grown over summer/autumn by students were planted out during May/June 2021. A total of 1579 trees (435 stringybarks and 1144 associated species) were planted.

In 2021-2022, more than 365 students and 34 teachers/parent helpers were engaged in the program bringing the total number of participants to 403. Close to 1200 suitable feeding trees (stringybarks associated species) were planted at RTBC habitats across their range in the South-East of South Australia.

Over the 2023 winter, 162 students helped to plant out more 1790 trees, consisting of more than 500 stringybark trees at seven revegetation sites.

5-year funding comes to an end (June 2023)

The 5-year National Landcare program funding for the current (2018) Kids helping Cockies project came to an end in June 2023. Participating schools include Allendale East Area School, Frances Primary School, Lucindale Area School, Nangwarry Primary School, Naracoorte South Primary School, Newbery Park Primary School, Rendelsham Primary School and Tenison Woods College.

Achievements over the last 5-years of the ‘Kids helping Cockies’ program include engagement with over 1930 students and 208 staff from 12 schools in south-east South Australia. A total of 177 events consisting of presentations, seed collection, seed sowing and planting, seedling maintenance/thinning and planting at revegetation sites have been held over the five years. Students have helped to propagate thousands of stringybark seedlings and planted more than 2700 food trees for Red-tails whilst also forming a strong bond and understanding of the conservation needs of the RTBC within the community.

This project has been a joint partnership between Limestone Coast Landscape Board, BirdLife Australia, Zoos Soth Australia and Trees For Life.

New funding for the Wimmera

The Kid’s helping cockies project will continue in the Wimmera CMA area from 2025 – 2028 as part of the Securing Girran (South-eastern Red-tail Black Cockatoo) habitat – 'now and for the future’ project. With partnerships of schools in the Wimmera the project aims to achieve 3ha per year of new stringybark and buloke habitat which will become a valuable addition to the Red-tail’s habitat in the Wimmera.

Glenelg Hopkins CMA revegetation of stringybark feeding habitat

The GHCMA is calling on interested landholders in the Glenelg Hopkins CMA area to contact them about being supported to undertake revegetation of stringybarks to increase the food supply for Red-tails. Key areas are Heywood, Hotspur, Dartmoor, Strathdownie, Bahgallahand Dergholm. Any land which contains Red-tails is important, even small areas dotted around the known distribution of the Red-tail habitat can make a big difference.

More information contact: Ben Zeeman at the Glenelg Hopkins CMA b.zeeman@ghcma.vic.gov.au 0411 311 328 or Dave Warne at Greening Australia DWarne@greeningaustralia.org.au

Communities Helping Cockies project

This project is located in the south east of South Australia and supported by the South East Natural Resources Management Board.

Securing a future food resource for Red-tails - ‘Cockies Helping Cockies’ project

Landholders in the south east of South Australia in the Redtails range have been able to access funding to assist with protecting existing remnant Stringybark habitat and/or revegetating areas on their property.

The ‘Cockies helping Cockies’ project has been running since 2012 with partnerships between Zoos South Australia, the Australian Government’s National Landcare program, Limestone Coast Landscape Board, BirdLife Australia and Trees for Life. With new funding secured by the Limestone Coast Landscape Board (LCLB) the project will continue at least up to 2028. Part of the project will include 64ha of revegetation work planned between 2025 - 2027.

Over the years the project has achieved revegetation of 286.2 ha of stringybark habitat and fenced 310.8 ha of existing stringybark remnants from stock. This has included the establishment of new shelter belts, paddock trees and patches, infill of existing stringybark remnants and installation of 1785 mallee mesh guards to protect from browsing kangaroos and stock.

Ninety-two landholders have been engaged over the period, with an incredible 19,678 stringybark seedlings (Brown and Desert Stringybark) planted across 187 sites within the Redtail’s range in South Australia.

Buloke revegetation in the Red-tails range in south east South Australia.

As part of the National Landcare Program Communities helping Cockies project, Trees For Life are revegetating buloke in the red-tail’s range in South Australia which occurs on the fertile heavy clay soils between Naracoorte and Bordertown. The Naracoorte-Lucindale Council are supportive of the project.

The area is highly productive for agriculture and sites available to revegetate bulokes can be limited so roadsides and disused rail lands have been a focus with 1000 Buloke seedlings being planted over winter 2019. Landholders who would like to have bulokes planted on their property can contact

Cassie CassieH@treesforlife.org.au or 08 8406 0500.

Glenelg Hopkins CMA

Red-tail Recovery’ project

Over the next four years (2025-28) the GHCMA will work with partnership organisations to carry out the following work to improve habitat.

- Pine control works (completed) including - 482 ha of pine removal by DEECA from the Drajurk State Forest, and 120 ha of pine removal by the Burrandies Aboriginal Corporation from a stringybark remnant owned by Nature Glenelg Trust, in Roseneath State Forest

- Working with Dave Warne to revegetate 40 ha of stringybark habitat. Potential sites will be assessed sites early 2025 with the intention to start planting in winter 2025

Wimmera CMA

‘Securing Girran (South-eastern Red-tail Black Cockatoo) habitat – now and for the future’ project.

From 2025 – 2028 the Wimmera CMA will work with partner organisations to help secure Redtail habitat through the following initiatives:

- continuation of the Kids Helping Cockies

- long-term (10 year) management agreements with private land-owners for the protection of 50ha of habitat

- revegetation of 400 ha revegetation of infill stringybark habitat and 20ha of Buloke habitat in partnership with

- Greening Australia

- permanent protection of 58ha of habitat area under Trust for Nature Covenants

- broad scale land management measures in partnership with Department of Environment Energy and Climate Action (DEECA) to improve the condition of the forests in the South-west Wimmera, including:

- 10,000 ha of predator control

- 12,000 ha of herbivore control

- 10,000 ha of weed contro

- monitoring by WCMA staff to determine outcomes

A pair of Red-tailed Black-cockatoos (female left; male right). Image courtesy Sky McPherson, RTBC Recovery Team.

Previous projects

Illegal birding

In 2017 a Victorian state-wide wildlife compliance operation 'Operation Eclipse' was implemented by DELWP’s Wildlife Officers. Members of the public are encouraged to report people who may be unlawfully keeping and trading in Red-tailed Black-cockatoos or people behaving suspiciously at or near key habitat locations; call DEECA’s Customer Call Centre on 136 186.

Evidence that revegetation works

A stringybark revegetation habitat demonstration site was set up in 2009 at ‘Lantara’ Lucindale by the ‘Cockies Helping Cockies’ project in partnership with the landholders who have been involved in the project since its inception. In 2018 Red-tails were observed feeding on fruit of the stringybarks planted just nine years ago. This the first known record of

‘Food for the Future’ project

This project aims to improve the habitat of the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-cockatoo in the Wimmera.

Wimmera CMA in partnership with Birdlife, Greening Australia, Trust for Nature, Barengi Gadjin Land Council and the Kowree Tree Farm Group with funding from the Australian Government’s Regional Land Partnerships of the National Landcare Program will take action to improve the habitat of the SERTBC, commencing 2018.

The project will focus on 7 key activities:

- Habitat Incentives Program: targeted financial assistance to undertake management actions that improve the condition of SERTBC habitat on their properties.

- Scattered Paddock Tree Project: supporting local schools to grow and plant 1000 scattered stringybark and buloke trees at key sites on private land.

- Nest boxes: 25 nest boxes will be constructed and installed at priority nesting sites in the Wimmera.

- Planting Bulokes: 10,000 Bulokes will be planted on 35ha of the Ozenkadnook Bank Australia Conservation Reserve.

- Citizen Science Hollows audit: the local community and volunteers will help to assess the availability of large nesting hollows at 5 locations.

- Indigenous ‘Red-tail Rangers’: the Wimmera CMA will work with Barengi Gadjin Land Council and the local indigenous community to engage locals to participate in recovery actions.

- Community Support and Engagement: BirdLife Australia and the Recovery Team will manage and coordinate core recovery plan monitoring and community engagement activities.

For more information or to get involved please contact Luke Austin at the Wimmera CMA or the SERTBC Project Coordinator on 1800 262 062.

Nest boxes in the Wimmera

As part of the Wimmera Catchment Management Authority’s ‘Food for the Future’ program. 25 new nest boxes were installed in 2019 on private properties across the Wimmera region by the Recovery Team and volunteers.

The nest boxes have been made from corrugated plastic piping with a steel coversheet for insulation and strong internal ladder to allow the birds to easily climb in and out. The design includes an open top, whereas previous versions of our nest boxes had a cover. Removing the top has been found to reduce use by galahs and white cockatoos in West Australia

The boxes will be monitored this breeding season to determine whether any Red-tails are using them with bioacoustic monitoring equipment.

Nest boxes in south-east SA

This project includes; BirdLife Australia, Limestone Coast Landscape Board and funds provided by the Australian Government.

Over the last two years, 50 new nest boxes have been installed at private properties within the bird’s range in the south east SA region. The new nest boxes are made from corrugated pipe with an internal ladder that runs down the inside of the box to allow the birds to navigate in and out. A layer of wood chips is placed in the bottom of the box to provide a nesting base, as well as two wooden posts for the birds to chew on while inside the nest. The boxes are deep (1.5m) and not fitted with lids to reduce competition by other hollow-nesting cockatoos, such as Galahs who often prefer a ‘roof’ over their nest. Trees with the nest boxes are collared to prevent terrestrial predators such as Common Brushtail Possums from climbing the tree and accessing the box.

Three of the 25 boxes installed in February 2020 were used by nesting pairs over 2020-21 breeding season which also contained nestling birds detected by acoustic monitoring. Source: Redtail news No 53.

Nest box audit and replacement

In 2023, an audit of 50 nest boxes which had been installed in the late 90’s/early 2000’s was carried out to assess their condition and carry out repairs/replacement. In addition, 50 new nest boxes were installed. Funding for this work was from a grant through the Australian Government Environmental Restoration Fund.

A total of 150 nest boxes were checked and maintained in 2025. In addition, 24 new nest boxes were installed with funding from the Australian Government National Heritage Trust program.

Increasing critical food supply for the endangered South-eastern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo

This project was funded by DELWP, Biodiversity Response Plan, which involves a partnership between Trust for Nature (TFN) and private land conservation – Snape Reserve Committee. The aim is to plant 30,000 Stringybarks in degraded private land remnants which were cleared in the past but are now under TFN covenants. These areas are ideal because they are managed primarily for conservation and have already had a great deal of weed control carried out which has resulted in areas of natural regeneration.

In 2020, Greening Australia undertook a major tree planting effort. In the Glenelg-Hopkins region the focus was on Crown Land forests where controlled burning has resulted in canopy scorch. In the Wimmera the focus was on areas of private land under conservation covenant where the vegetation has been previously cleared. The project resulted in 30,000 desert stringybark seedlings planted across 500 hectares of private land under conservation covenant in the Wimmera and 41,000 desert stringybarks established through a combination of planting and hand direct seeding across 400 hectares within Drajurk State Forest in the Glenelg Hopkins catchment. Funding for the project was provided by the Victorian Government’s Biodiversity Response Plan.

Jess Gardner - Greening Australia 0437 958 259

More information about this project

Limestone Coast Paddock Tree Project

Paddock Trees provide key nesting hollows and feed sites for the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo, This project aims to establish a new generation of paddock trees by planting and guarding 1,800 seedlings on private land, as well as protecting 25 existing paddock trees. The project has received overwhelming interest to its first call for Expressions of Interest from landholders which has enabled the project to achieve its targets within the first two years of the project.

Several different guard types are being trialled. The project will produce a number of practical fact sheets and videos

describing the most successful guards and tips to install and maintain them.

Contact: Samantha Rothe – Trees for Life

Partnerships

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Recovery Team

The recovery team has members from Birdlife Australia, Victorian & South Australian State Government and Federal environment agencies, Glenelg Hopkins and Wimmera Catchment Management Authorities, South Australian Farmer’s Federation, Forestry SA., Trust for Nature, Threatened Species Network, Local Government and other specialists knowledgeable about the species or its habitat. The team is involved with extension, research, planning and habitat protection activities. Recovery Team site Redtail

Birdlife Australia

Undertake flock counts. Confirm the relationship between the location of nests/location of nesting hotspots and distance to stringybark. Undertake Stringybark seed counts.

Trust for Nature

Permanently protect habitats through covenants and land purchase. Work has been underway towards protecting habitat through conservation covenants. There are now 50 covenants in the GHCMA region and 90 in the Wimmera region. Significant areas of Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo habitat have been covenanted since July 2006, 336 ha of habitat in the Wimmera and 104 ha in Glenelg Hopkins region.

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate ACTION (DEECA)

Manage threats to the productivity of scattered feed trees and minimise permitted clearance habitats incorporating adequate off-sets.

Ensure that potential impacts on Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos are considered in planning and conduct of ecological burns and wildfire suppression actions. Red-tailed Black-cockatoo and fire study 2009. Also in 2019 a strategic bushfire risk assessment for the South West region of Victoria. This project includes developing selected locations for targeting burns which will reduce the impact on SERTBC habitat quality.

Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMVic) undertake a range of pre-burn tasks under the DELWP Bushfire Management Strategic Plan to help protect Red-tails. Post-burn severity mapping is carried out to ensure burns are conducted in-line with the Strategic Plan. Key pre-burn tasks include seed crop assessments in proposed burn areas. If a high seed crop is recorded or more than 20 Red-tails recorded in the days prior to ignition, the burn will be deferred.

Forest Fire Management Victoria - Glenelg Pine project: a 3-year project to improve, protect and rehabilitate stringybark woodlands by removing pine tree wildlings. The project covers 3,780 hectares of public land, from the Lower Glenelg National Park in the south and as far north as the Dergholm State Park. As at January 2021, a total of 4672ha has been treated. This included 498ha of high infestation sites and approximately 2932ha of follow up treatment including areas impacted by 2019-2020 bushfires such as Weecurra State Forest. This project has resulted in rejuvenation of landscapes, regaining woodland ecosystems, and greatly benefiting flora and fauna including the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo.

Controlling pine invasion in pine invasion in State Forests 2022. The project is a partnership between GHCMA and DELWP. The aim is to reduce pine invasion down to a manageable level across 1166 ha of Stringybark habitat, ensuring the health of Stringybark fruit production and future recruitment. Areas include DELWP managed forests, Roseneath State Forest, Drajurk State Forest, Nangeela State Forest and Wilkin Flora Reserve. In 2022, GHCMA also undertook surveys to determine the pine wildling problem on private properties adjoining the State Forest areas.

Assess illegal trade: determine the magnitude of the illegal trade in South-east Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos. Conduct surveillance and information gathering relating to illegal trade in Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo.

State-wide wildlife compliance operation 'Operation Eclipse' 2017. In addition on-going reporting. DELWP’s Wildlife Officers encourage Victorian's to report people who may be unlawfully keeping and trading these birds or people behaving suspiciously at or near key habitat locations; call DELWP’s Customer Call Centre on 136 186

Greening Australia

Significant revegetation projects have been undertaken in the Drajurk State Forest near Casterton and Rennick State Forest near the South Australian border involving the control of Pines and Coastal Wattle and planting of Desert Stringybark (Eucalyptus aranacea) and Brown Strinybark (Eucalyptus baxteri) . This project is carried out by Greening Australia supported by the Australian Government through the National Landcare Programme.

In 2018, over 2,000 hectares of public land revegetation was completed focusing on Stringybarks to increase food supply for the RTBC. The project involved tube-stock and hand direct seeding in 2017 and 2018. Over 150,000 tube-stock seedlings were installed during the project. Hand direct seeding plots were deployed at a rate of 250 per hectare.

Greening Australia will establish a further 70,000 Stringybarks during 2019 – 2021 as part of Victoria’s Biodiversity Response Planning.

In 2019 involved with planting of 30,000 Strinybarks on Trust for Nature covented land as part of the Increasing critical food supply for the endangered South-eastern Red-tailed Black Cockatoo project.

In 2020, 30,000 desert stringybark seedlings planted across 500 hectares of private land under conservation covenant in the Wimmera and 41,000 desert stringybarks established through a combination of planting and hand direct seeding across 400 hectares within Drajurk State Forest in the Glenelg Hopkins catchment.

Wimmera CMA

Protect 40 Buloke scattered paddock trees per year. Plant or encourage regeneration of key habitats: 18,000 new Buloke plants per year. A Habitat Tender is being managed through the CMA, prime habitat areas have been identified with the first round of payments for securing Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo habitat being made by the end of 2006. Report annually the number of scattered paddock trees protected.

Glenelg Hopkins CMA

Protect 40 Desert Stringybark scattered paddock trees per year. Plant or encourage regeneration of key habitats: 10,000 new stringybark plants per year. Glenelg Hopkins CMA and Conservation Volunteers Australia will treat pine wildlings to improve habitat for Red-tailed Black Cockatoos over a 7000ha area within Drajurk State Forest and Wilkin Flora Reserve.

Commencing in 2020, the Glenelg Hopkins CMA will be undertaking several projects focused on conservation of the SERTBC.

- revegetation of food trees is being managed by Greening Australia, with a focus on establishing scattered paddock trees on private land.

- enhance connectivity between stringybark remnants on private land and the State Forests.

- introduction of Aboriginal burning methodology into Red-tail habitat within State Forests which aims to reduce canopy scorch, thereby protecting stringybark fruit whilst also satisfying fuel reduction objectives.

- Partnership with DELWP on pine wildlings control in State Forests and adjoining private land.

GHCMA contact: Ben Zeeman, 0411 311 328,

Glenelg Shire

In May 2018, the Glenelg Shire amended Schedule 3 to the Environmental Significance Overlay (ESO3) and increased the coverage of ESO3 to include additional South-eastern Red-tailed black cockatoo (SeRtBC) habitat in the Shire.

This amendment means a planning permit be obtained to remove, lop or destroy SeRtBC habitat on land covered by the schedule, including:

• Brown or Desert Stringybark with a trunk diameter greater than 30 centimetres at 1.3 metre above ground level; and

• Hollow bearing Eucalyptus tree with a trunk diameter of greater than 40 centimetres at 1.3 metres above ground level.

West Wimmera Shire

The WW Shire and Department of Sustainability and Environment Horsham are developing an Environment Significance Overlay to further protect Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo habitats on private land in the Shire. Limit the impacts of stubble burning on remnant paddock trees.

Arthur Rylah Institute (ARI)

Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Roadside foraging study: Research is proposed to provide information on the age of trees in which Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos will feed.

Nature Foundation of South Australia

Funding for the Nest Incentive Scheme which can pay members of the public (especially landholders) for finding Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo nests. Payments are available for discovery of new nests and for finding existing nests.

Conservation Volunteers Australia (CVA)

Support for the the Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo by undertaking tree planting to promote future feeding and roosting areas. Thousands of trees have been planted at the Casterton water treatment works and CVA planted 1000 Buloke seedlings at Clear Lake and 1500 at Bringalbert. Further plantings are planned in the Edenhope, Casterton and Apsley areas. Pine wilding removal is also carried out to maintain the stringybark forest as well as protection, propagation and planting of stringybark trees on private land. See Glenelg Hopkins CMA above.

The University of Melbourne Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences

In 2015 researchers worked with the Recovery Team to trial a method of surveying for disease by testing swabs obtained from nest sites used by Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos.

Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia

Development of a range of ecological fire management measures to provide adequate feeding resources for the Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo by reducing the amount of seed scorch during burning. DEWNR South Australia Ecological Fire Management Strategies

Conservation Volunteers Australia and Birdlife Australia

Nest tree collars are maintained to prevent possums from occupying nest hollows.

Kowree Farm Tree Group (KFTG)

Growing seedlings and planting out as widely spaced individually guarded paddock trees in the Casterton area. The reason for planting paddock trees is that stringybarks in paddocks produce up to 26 times the seed that they produce in a forest.

The Group, as part of the Kids for Cockies project is now seeking suitable farm sites for planting paddock trees within the Red-tail’s Victorian range. Suitable sites for either Stringybarks (sandy country) or Buloke (clays). There is a preference for sites that are grazed only by sheep but properties grazed by cattle will still be considered. The trees and sheep proof guards are free, and grazing still possible.

In 2018 the KFTG planted 1,300 individually guarded trees (80% Stringybark, 20% Buloke). The plan for 2019 is 1,000 individually guarded trees (70% Stringybark, 30% Buloke).

In 2019, over 1,000 trees (Bulokes and stringybarks) were planted.

In 2020, the Kowree Farm Tree Group project: ‘Restoration of the South-east Red-tail Black Cockatoo Feeding Habitat’ resulted in the planting of 1,100 Desert Stringybarks and 280 Bulokes on four properties in the Mallee.

Interested landholders can contact Ben Gaylard via email or 0429 294 485.

Nature Glenelg Trust

In partnership with Glenelg Hopkins CMA, Birdlife Australia, SE Red-tailed Black Cockatoo Recovery Team, Greening Australia, Parks Victoria and DEWLP have undertaken a habitat restoration project in the Wilkin landscape. The project ran from June 2017 to April 2020. One aspect involved improving the extent and condition of brown stringybark woodland, which is regionally significant for South East Red-tailed Black Cockatoos. Specifically, this will be achieved by treatment of 300 Ha of woodland area removing Pinus radiata and Acacia longifolia wildlings.

Australian Bluegum Plantations (ABP)

ABP is working with the Redtail recovery team to help manage habitat for the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo at a plantation near Casterton. A number of old telephone poles have been installed across the site housing artificial nests. In 2019-20 at least 9 successful Red-tails fledging were recorded from the site. ABP has also developed an overarching Habitat Management Plan in consultation with the Red-tail Recovery Team. Australian Bluegum nestbox project

Zoos South Australia

'Cockies Helping Cockies’ Project - Farmers revegetating patches, shelter belts and paddock trees as well as fencing and enhancing existing remnants in areas supporting existing stringybark habitat and/or where birds are known to feed and frequent. In 2021-2022, the project managed to create/restore 88 Ha of habitat across 45 sites involving the planting of 14,198 trees.

Portland North Primary School

Seed collection, propagation and planting for a school revegetation project specifically for the Red-tailed Black-cockatoo.

References & Links

- Commonwealth of Australia (2007). National Recovery Plan for the South-eastern Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne. Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Canberra.

- DEH (2000) Endangered Ecological Community, Buloke Woodlands of the Riverina and Murray Darling depression Bioregions.

- DEECA (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act Threatened List 2024, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, Victoria.

- Emison, B. (1996) Use of Supplementary Nest hollows by an Endangered Subspecies of Red-tailed Black Cockatoo, Victorian Naturalist, vol 113 (5), p262-263.

- Joseph L., Emison W.B., & Bren W.M., Critical assessment of the conservation status of red-tailed black-cockatoos in south-eastern Australia with special reference to nesting requirements :, Emu, 91(1), 1991, 46–50.

- Loyn, R., Cheers, G., Roberts, E., & Lucas, A. (2007) Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos and Bulokes: what determines which trees are used for feeding? A report to the threatened species section, Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services Division, Department of Sustainability and Environment.

- Maron, M. and Lill, A. 2004. Discrimination among potential buloke (Allocasuarina luehmannii) feeding trees by the endangered south-eastern red-tailed black-cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii graptogyne). Wildlife Research 31: 311-317.

- Maron Martine (2005) Agricultural change and paddock tre loss: Implications for an endangered subspecies of Red-tailed Black cockatoo, Ecological Management & Restoration Vol.6, (3); 206-211.

- RFA (2000) West Victoria Regional Forest Agreement between the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Victoria, March 2000.

- Venn, D.R., Fisher J. (1993) Flora & Fauna Guarantee Action Statement No.37: Red-tailed Black Cockatoo, DSE.

More Information

- Red-tailed Black-cockatoo Recovery site

- Victorian Flora and Fauna Gaurantee Action Statement No.37 Red-tailed Black-cockatoo (pdf)

- Red-tailed Black-Cockatoos and Bulokes: what determines which trees are used for feeding?

- DEWNR South Australia Ecological Fire Management Strategies

- Recovery Team Fire Management Strategy

- Flock counts survey summary

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 42 March 2016

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 43 November 2016

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 44 March 2017

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 45 December 2017

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 46 April 2018

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 47 December 2018

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 48 April 2019

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 49 December 2019

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 50 April 2020

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 51 December 2020

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 52 April 2021

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 53 December 2021

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 54 April 2022

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 55 November 2022

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 56 April 2023

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 57 December 2023

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 58 June 2024

- Birdlife Red-tail newsletter Issue 59 December 2024

Participate in the annual Red-tail count

On the 1st Sunday in May every year the recovery team calls on volunteers to help conduct the annual count by surveying over 60 sites across their range.

To register your interest or secure your search area for 2025, please do so via the website http://www.redtail.com.au/how-to-get-involved-in-counts.html

Random sightings

If you see a Red-tailed Black-cockatoo phone 1800 262 062, email or report your sighting via the Red-tail website

When reporting a sighting please remember to include: date and time, place (CFS/CFA map reference is appreciated), how many birds, what they were doing (i.e feeding, drinking, flying), and your name and phone number/email.

If you see people behaving suspiciously at or near key Red-tailed Black-cockatoo habitat locations in Victoria; call DELWP’s Customer Call Centre on 136 186.