SWIFFT Seminar notes 21 March 2024

Bat conservation

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 238 participants via Microsoft Teams. SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Also, thanks to Lindy Lumsden who chaired the session from the Arthur Rylah Institute and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

This seminar highlights some of the challenges facing bats, including threats and the need to improve community awareness on the conservation values and role of bats in our environment.

Key points summary

The Ecology and Conservation of Victorian bats – Our Fascinating Creatures of the Night

- Bats are more common and diverse than most people think. There are 24 species of insectivorous bats and 2 species of fruit bats in Victoria.

- Bats play important ecosystem roles.

- Bats face a range of threats which can impact on their roosting, feeding, access to water as well as direct predation and climate change.

- Bat conservation requires changing attitudes and reducing threats combined with research to learn more about their population status and requirements.

A small bat with big challenges: Survival and seasonal movements of the critically endangered Southern Bent-wing Bat and implications for conservation

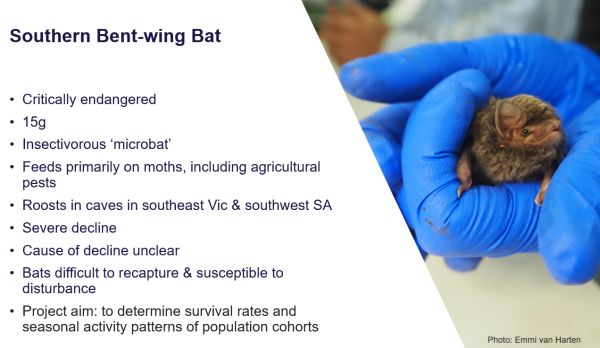

- The Southern Bent-wing Bat is Critically endangered and a National Priority Species under the Australian Government - Threatened Species Action Plan 2022 – 2032.

- A research project spanning three years at two study sites in South Australia found SBW bats are highly mobile and respond to seasonal changes much more than previously thought.

- The SBWB has a low reproductive rate and relies on high survival rates to maintain populations but in drought years the survival rate can be very low.

- Given impacts from habitat degradation and other human induced threats including climate change the recovery plan predicts the potential for further declines of 84-97% by 2056.

The establishment, growth and fluctuations of Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Victoria: challenges for the community and managers

- Flying-foxes perform important ecosystem services (long-distance pollination, seed dispersal), they frequently and regularly move vast distances and change camps.

- In many cases, we created the foraging and roosting conditions that suit them but climate change is contributing to range expansion.

- Camp relocations are rarely the solution, and typically lead to unintended and worse outcomes. We need education and management to live with and accept them.

Living with flying-foxes in Victoria

- Flying-foxes can congregate in large numbers which can cause issues, particularly where they are in proximity to where people live and also recreational areas.

- Flying-foxes love to feed on trees in backyards containing nectar or fruit but, in most cases, they are only around for a short time as once the flowering or fruiting is over, they will move on.

- All flying-foxes in Victoria are protected wildlife under the Wildlife Act 1975 which means it is illegal to wilfully disturb, harass or harm them.

- Do not touch or handle flying-foxes yourself, only people who are trained, vaccinated and wearing PPE should handle flying-foxes.

- The Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services team provides support for land managers dealing with flying-fox camps by providing advice on management actions and support the species as well.

List of speakers and topics

- The Ecology and Conservation of Victorian bats – Our Fascinating Creatures of the Night - Dr Lindy Lumsden - Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

- A small bat with big challenges: Survival and seasonal movements of the critically endangered Southern Bent-wing Bat and implications for conservation - Dr Emmi van Harten – DEECA

- The establishment, growth and fluctuations of Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Victoria: challenges for the community and managers - Dr Rodney van der Ree - Assoc Prof, National Technical Executive: Ecology School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne

- Living with flying-foxes in Victoria - Dr Leila Brook - Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

The Ecology and Conservation of Victorian bats – Our Fascinating Creatures of the Night

Dr Lindy Lumsden - Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

Lindy introduced her presentation by talking about how bats are an amazing and beneficial part of our native fauna but often misunderstood.

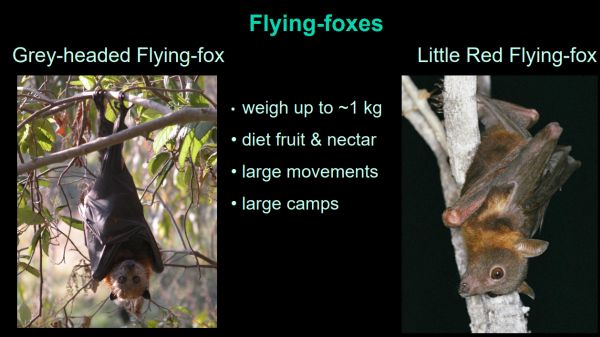

Flying-foxes (fruit eating bats)

Flying-foxes are generally more well known by people because they are readily seen. There are 2 species of flying-fox in Victoria;

Grey-headed Flying-fox (widespread across Victoria and can undertake long distance movement within Victoria and interstate).

Little Red Flying-fox (smaller than the Grey-headed Flying-fox), mainly confined to northern Victoria and more northern parts of Australia.

Insectivorous bats

Lindy has worked on studying insectivorous bats for over 40 years. They are less understood by the general community because they are difficult to see or hear. They are also very small, some weighing as little as 4 grams. Insectivorous bats play an important role in the environment as insect controllers, many species consume up to half their body weight in insects per night.

Insectivorous bats are found across a wide variety of habitats in Victoria, including farmlands, forests and urban environments.

Some species such as the Lesser Long-eared bat have widespread distribution whilst others species such as the Eastern Horseshoe bat have a very restricted range in Eastern Victoria.

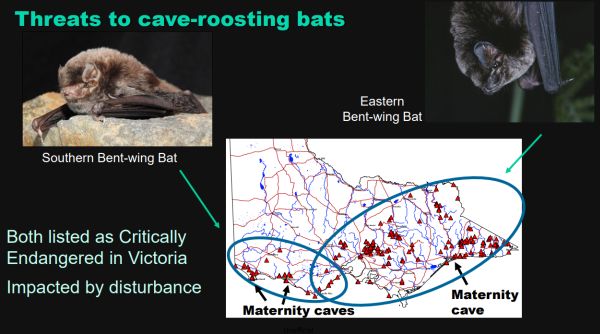

Rare and Specialised insectivorous bats

There are 5 species of insectivorous bats listed as threatened under the Victorian Flora & Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, FFG Threatened List (June 2023).

- Eastern Horseshoe bat – endangered

- South-eastern Long-eared bat - endangered

- Southern Bent-wing bat – critically endangered

- Eastern Bent-wing bat - critically endangered

- Yellow-bellied Sheathtail Bat - vulnerable

In Victoria, the South-eastern Long-eared bat is only known to occur in a very small area of old growth mallee vegetation in the Hatta area but through research a new area of habitat containing this species was recently discovered in Black Box vegetation in the Gunbower Forest area.

Research has also found a new species for Victoria, the Golden-tipped bat was discovered in rainforest in far eastern Victoria in 2022. This species is more widely distributed from NSW to Queensland. It has a unique and specialised feeding technique of hovering in front of spider webs and picking spiders out. It feeds exclusively on spiders and roosts on disused hanging birds’ nests.

Threats to insectivorous bats

Lindy discussed how threats to bats can impact on their survival in different ways. Some of the key impacts can be on:

- Roosts

- Food

- Access to water

- Predation

- Other mortality causes

- Climate change

Insect decline

Lindy highlighted the worldwide decline in insect numbers which is happening at the rate of 1-2% per year. Insectivorous bats are totally reliant on insects for their diet. It is not well understood what is leading to the downward trend in insect numbers and diversity. More about global insect decline.

Flying habits and risks

Species which have long narrow wings such as the White Striped-freetail bat fly around in the open fairly high above the canopy. This makes them vulnerable to flying into wind turbines.

Windfarms are known to cause mortalities to bats but more research is required to quantify the level of risk to bats and how to mitigate impacts on bats.

Threats to cave roosting bats

There are four species of cave roosting bats in Victoria. In particular, Lindy spoke about the Southern Bent-wing bat and the Eastern Bent-wing bat, both cave roosting bats which are extremely dependent on the viability of one or two maternity caves which provide the necessary conditions for raising juvenile bats and supporting the ongoing viability of the entire population.

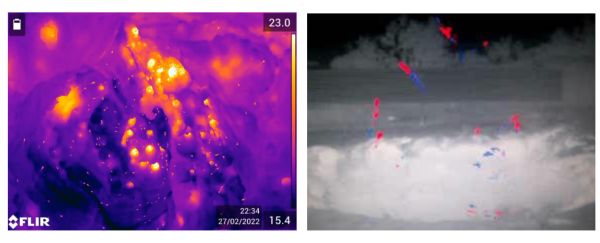

Research and Monitoring without causing disturbance

Lindy spoke about the importance of avoiding disturbance in maternity caves. She described the use of non-invasive methods to carry out research by employing thermal and infra-red cameras to detect and count bats.

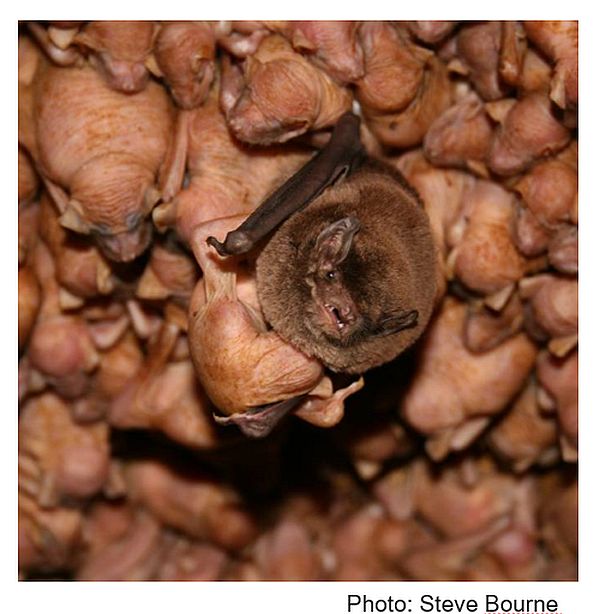

Understanding pup survival and mortality

Bat pups are about half the size of the mother. Congregations of pups are found in the cave to facilitate the retention of warmth. Lindy spoke about a concerning trend of pup mortality at both the Southern Bent-wing bat and Eastern Bent-wing bat maternity caves which can be a s high as 20-30% mortality. Additional research is being carried out to determine the factors which could be leading to such high mortality.

White-nosed Syndrome

Lindy explained that White-nosed Syndrome is a fungal disease which is deadly to bats. The particular fungus occurs in cold caves and is native to Europe but has been spread to North America. Lindy highlighted that in the vicinity of 6 million bats have been killed in North America since the fungus was spread there in 2006. Some populations of bats have been reduced by 96%.

Lindy issued an alert that the fungus can be easily spread by bats and also people as the fungus can be transported from cave to cave on a person’s clothing and equipment. The fungus is not yet in Australia but if it were to get here it would pose a significant threat to our cave roosting species, considering only one or two cave support the entire populations of the bent-wing bats.

Threats to tree-hole roosting bats

Most species of insectivorous bats (21 of the 24 species) roost in tree hollows which provide critical habitat. Both dead or live trees can contain hollows or even cracks which bats can use. Lindy highlighted that dead trees comprise valuable roosting sites and should be retained. Even insignificant looking cracks can support bats.

Lindy spoke about the continued decline of old dead trees across the landscape as one by one they are being knocked down due to clearing or burning. There is also a sever lack of recruitment of paddock trees across the landscape. Considering old habitat trees can take 100 years to form these are not being replaced quickly enough given the current rate of decline.

Bats in the urban environment

Bat have the capacity to co-exist in an urban environment. Urban environments can be built up areas anywhere in Victoria. In Melbourne and surrounds there are 16 species of insectivorous bats. Unfortunately, many old trees and limbs are removed due to safety concerns but where possible and safe to do so old trees should be retained as they provide essential habitat for bats.

Key points from questions

Harp traps and mist nests are sometimes used to monitor various species or when there is a need to attach monitoring devices but in more recent years the use of echolocation technology combined with AI is being employed.

Bats consume a high proportion of moths in their diet, including the Bogong Moth which has experienced a widespread decline but the impact on bats through reduced food source is still unclear. In recent years there have been moves to analyse the species of insects consumed by bats by studying DNA of their diet.

Planting vegetation which could be beneficial to moths is viewed a positive thing but at this time there is no specific species list available.

Bat boxes must be made of thick, well-sealed timber with an opening at the bottom. Bat boxes can supplement bat habitat but should not be used as a justification for removing old habitat trees.

There has been testing on deceased pups at maternity caves but no sign of disease detected. Further research is required to determine what is causing high pup mortality.

The cave at Naracoorte in South Australia is monitored using infrared cameras which can be viewed by the public.

eDNA can be used to identify species of bats, with advances of sampling eDNA from the air being trialled.

Insectivorous bats can move long distances at night to feed with some variation between species. A study in northern Victoria found bats were regularly travelling 13km from the roost to foraging areas. The Southern Bent-wing Bat can move 20-30km or more in a night. A major factor in the movement across farmland areas is the availability of adequate tree cover, being paddock trees or linear belts.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

A small bat with big challenges: Survival and seasonal movements of the critically endangered Southern Bent-wing Bat and implications for conservation

Dr Emmi van Harten – DEECA

Emmi pointed out that her presentation is based on her PhD studies at La Trobe University.

Emmi provided an overview of the Southern Bent-wing Bat and the objectives of her PhD - Determining the survival rates and seasonal activity patterns of population cohorts. Given the continued decline of the Southern Bent-wing Bat (SBWB) across its range research into this species is very important.

The Southern Bent-wing Bat is a National Priority Species under the Australian Government - Threatened Species Action Plan 2022 - 2032.

About the Southern Bent-wing Bat

Study sites

Two study sites were used, both in South Australia and approximately 70km apart. A major maternity cave at Naracoorte and a non-breeding cave at Glencoe.

Use of passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags

The PIT-tag study is recommended in the Recovery Plan. These tags are fitted to selected bats, they provide a unique ID marker which lasts the lifetime of the bat.

Once the tag is fitted it enables passive detection of bats by using antennas or hand-held readers. Emmi spoke about the limitations of traditional close-range devices which had the potential to cause deviation in the bat’s flight so refining the way the new PIT tags could be used to detect bats without causing any disruption was a key part of the research.

More information: High detectability with low impact: Optimizing large PIT tracking systems for cave-dwelling bats, Emmi van Harten, Terry Reardon, Lindy F. Lumsden, Noel Meyers, Thomas A. A. Prowse, John Weyland, Ruth Lawrence. Ecology and Evolution 15 September 2019 https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5482

Data collection

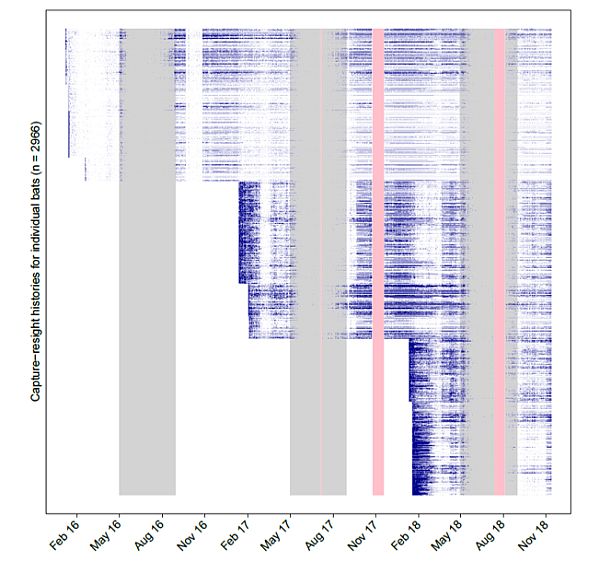

Emmi spoke about the effort that went into tagging and monitoring. Both adults and juveniles of both sexes were trapped, measured, tagged and released. Over 3 years (2016-2018) about 1000 bats/year were PIT-tagged and logged with over 1.4 million unique detections, 97% of tagged bats were detected at least once.

Emmi pointed out that part of her research was to ensure there were no negative impacts on bats.

The only area of concern was associated with loss of fur at the injection site due to surgical adhesive but this proved to be a temporary event as bats inspected 3 years after tagging were in good condition with no signs of injury from having the tag fitted.

More information: Recovery of southern bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae bassanii) after PIT-tagging and the use of surgical adhesive Emmi van Harten, Terry Reardon B , Peter H. Holz C , Ruth Lawrence D , Thomas A. A. Prowse E and Lindy F. Lumsden F., Australian Mammalogy 42(2) 216-219 https://doi.org/10.1071/AM19024

Data analysis, survival

Emmi spoke about the high detection rate with over 17.8 million detections over 3 years. A method to collect daily detection history was created which showed the daily detections.

Using detection data combined with CJS model using Rmark, Emmi was able to gain further insights into encounter probabilities, population projections, age, sex, female reproductive condition, and the interaction between season and year.

Emmi showed some charts showing yearly variation in season survival. There were low survival rates in the summer and autumn of 2016 which coincided with sever drought conditions in the area. When the landscape was replenished with rains in 2017 the survival rates recovered. Emmi further explained that there are differences in survival rates between juveniles, adults, males and females, non-breeding females and lactating females.

Overall results suggest that challenging conditions during the 2016 dry breeding season impacted on species viability.

Other considerations regarding survival include:

- Breeding cycle relies on mass congregation

- 90% natural vegetation is cleared

- Most wetlands have been drained

Results suggest that actions to boost habitat availability within proximity to maternity caves may support survival during the breeding period.

Population projections

Bats such as the SBWB have low reproductive rates and rely on high survival rates to maintain populations.

Using survival data and other known or ‘best guess’ parameters, population growth/loss was estimated for each study year. Survival results suggest continued population decline in each study year, especially during times of drought.

Even if high fertility and high pre-volant juvenile survival are assumed survival rates may worsen in the future due to climate change.

Survival results used in a PVA to inform the re-assessment of the SBWB under the EPBC Act. Predicted further declines of 84-97% by 2056.

More information: Novel passive detection approach reveals low breeding season survival and apparent lactation cost in a critically endangered cave bat, van Harten E, Lawrence R, Lumsden LF, Reardon T, Prowse. Springer Nature 1/12/2022

Movement

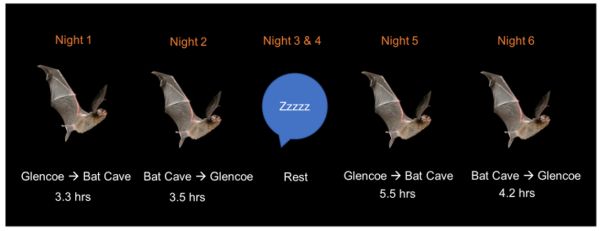

Emmi spoke about findings from her research which shed new light on the movement of the SBWB. It was previously thought that nearly all SBW bats in south-east SA were at the main Bat Cave during the summer breeding season, and then migrate to wintering sites. However, it is now known that during the summer several thousand bats were at the non-breeding cave at Glencoe which comprised a high proportion of adult females and young. These bats return to the maternity cave in spring. A new understanding of movement has enabled refinement of the daily detections history data which now includes data from both the maternity cave and the bat cave.

Movement pattern summary

- Seasonal movement patterns are evident, including key movement periods

- New movement event identified in juveniles and adult females but movements between caves also occur throughout the year and varies between individuals

- Seasonal movement (from “migration”)

- Non-breeding caves (from “wintering caves”)

- Bats more active in winter than expected

More information: Seasonal population dynamics and movement patterns of a critically endangered, cave-dwelling bat, Miniopterus orianae bassanii, Emmi van Harten, Ruth Lawrence C, Lindy F. Lumsden D, Terry Reardon E, Andrew F. Bennett and Thomas A. A. Prowse, Wildlife Research Vol. 49 (7), CSIRO Publishing

Emerging threats

White-nosed Syndrome - a fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) is capable of killing hibernating bats. Whilst not detected in Australian bat populations yet, there is a high-level biosecurity risk that this fungus could be transported to Australia, particularly on clothing, gear, and equipment from people who have been in caves overseas.

Impacts from wind turbines – Emmi discussed how the new understanding of bat movement, far more than was previously thought needs to be factored into windfarm planning and management.

The Southern Bent-wing Bat Action Statement under the FFG Act includes ‘low-windspeed turbine curtailment’ as a conservation measure for the Southern Bent-wing Bat to reduce mortality at wind farms.

National Recovery Plan

Emmi spoke about how actions being implemented under the recovery plan may help to change the declining trajectory for this species. In particular, habitat restoration, minimising human disturbance at caves, climate action, low-windspeed turbine curtailment and biosecurity.

Emmi acknowledged all the volunteer hours spent on the project as well as the support from La Trobe University colleagues.

Publications – Emmi van Harten

Key points from questions

It is possible that the bats have always been undertaking high levels of movement but there could be some changes in the patters over time in order to reach certain foraging areas.

There are projects underway to restore wetlands and carry out revegetation in the vicinity of the bat population. A key project is Nature Glenelg Trust project at Mt Burr swamp.

Education of private landholders about the needs of bats is being carried out.

There is probably no specific need for creating special vegetation corridors for the purpose of SBWB as they are capable of movement across the landscape which requires a broader habitat recovery approach.

In times of drought the pups were observed to be in very poor condition.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

The establishment, growth and fluctuations of Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Victoria: challenges for the community and managers

Dr Rodney van der Ree - Assoc Prof, National Technical Executive: Ecology School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne

Rodney introduced his presentation by discussing the polarity in how people view flying-foxes; they either like them or hate them. More broadly, the flying-fox story in Victoria is one about human conflict with wildlife.

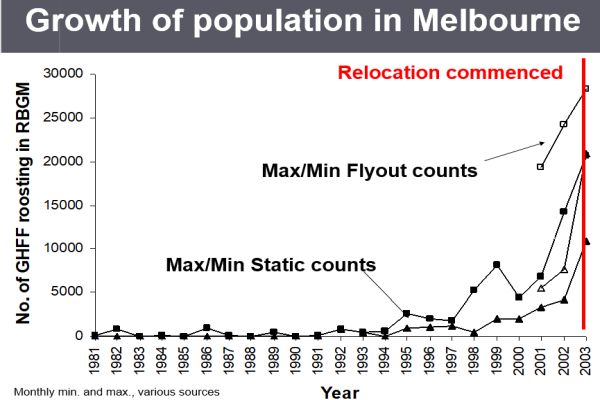

In the 1980’s there were very few flying-foxes in Victoria, they were viewed as an unusual occurrence but by 2024 the situation has changed with high levels of human and flying-fox co-existence.

Flying-fox distribution

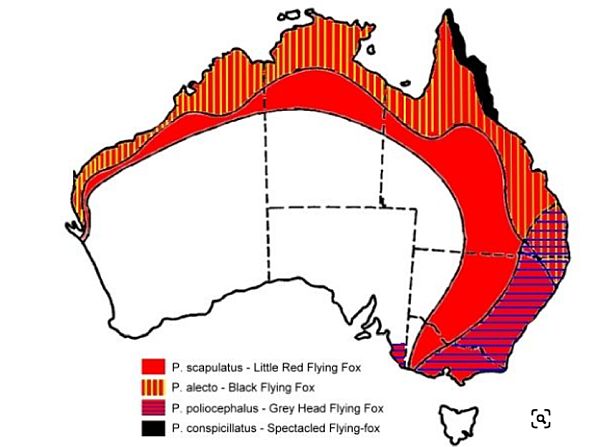

Rodney provided an overview of the flying-fox species in Australia and their range. Spectacled Flying-fox – Cape York, Queensland, Black Flying- fox – across northern Australia from Shark Bay to just below the New South Wales/Queensland border, Little Red Flying-fox – across northern Australia and down through Queensland, New South Wales and into Victoria and Grey-headed Flying-fox – from southern Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and south-east South Australia

Roosting & feeding

Rodney explained that a location of roosting flying-foxes is referred to as a colony or camp and can contain anything from hundreds to tens of thousands of animals. In Victoria, many camps are around 5 to 35 thousand animals. When feeding, flying-foxes are dispersed into small groups feeding mainly on blossoms and fruit from both native and non-native species of plants.

Roosting habitat preferences

Camps are typically near water (coast, lakes, river, swamp) on hot days they drink by gliding down to touch the water and get their chest wet then return to a tree and drink by licking the moisture off their chest.

Camps have structural components – trees to hang off – tall eucalypts, dense rainforest, melaleuca scrub, mangroves, palms, “European” trees (conifers).

Camps are usually located near or centrally to a source of food.

When roost areas become a problem

Rodney discussed the competition for space when flying-fox camps are in close proximity to residential areas.

A more recent issue in Victoria is when flying-foxes establish a camp in an area that they have never been before. Rodney pointed out that many of the botanic gardens in regional Victoria have had the necessary habitat to support new camps which can cause disruption to the way parks and gardens are managed.

The pre-history of Grey-headed Flying-fox (GHFF) in Melbourne

Rodney gave a brief overview of GHFF camp development and growth in Victoria. He pointed out that historically most records were in summer and autumn and that the flying-foxes would migrate north during winter.

- First record (Museum) 1884 from Queenscliff

- Occasional records per decade until 1970s

- First record at Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne 1952, and again in 1981

- 1000 in Autumn 1986, with 10-15 over-wintering for the first time at the RBGM

Why did the flying-foxes come to Melbourne?

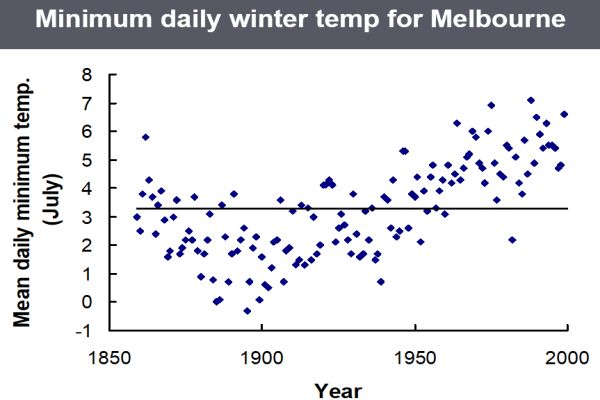

- Climate change is a contributor, Melbourne is warmer with fewer frosts than 40 years ago

- Storms interstate can cause food shortages forcing movement to new areas

- Habitat loss through clearing or fire elsewhere in range can induce movement

- Melbourne contains an all-you-can-eat smorgasbord with a more diverse and more abundant all year-round food source

Increased food plants for GHFF

Grey-headed Flying-foxes are known to feed on about 180 species of plants. In Victoria there are 32 species of indigenous plants used for feeding with 11 indigenous plant species used for feeding in Melbourne. Since European settlement the extent of food source has increased with about 150 species of introduced plants suitable as being flying-fox food source. Rodney pointed out that favourite food species such as Morton Bay Fig tree and Spotted Gum have been extensively planted in Melbourne. Flying-foxes regularly move into the built-up areas of suburbs to feed on street trees and in backyards.

Relocation trial

Rodney spoke about past attempts to move flying-foxes out from the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne with a formal 3-year relocation trial in 2003. Despite a range of passive measures being used to attract the animals to a new area the only thing that worked was noise disturbance which was a 6 months project to eventually force the bats to move to the preferred location at Yarra Bend. Rodney pointed out that this was a rare, successful attempt to relocate the flying-foxes. In most cases relocation efforts are a failure and just push the problem somewhere else. There are also several animal ethics issues associated with stressing animals.

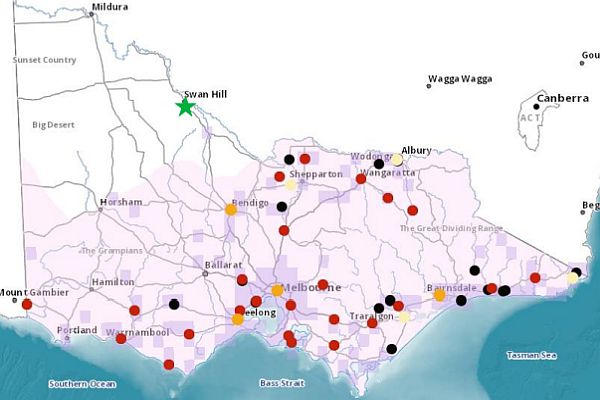

Recent history of flying-foxes in Victoria

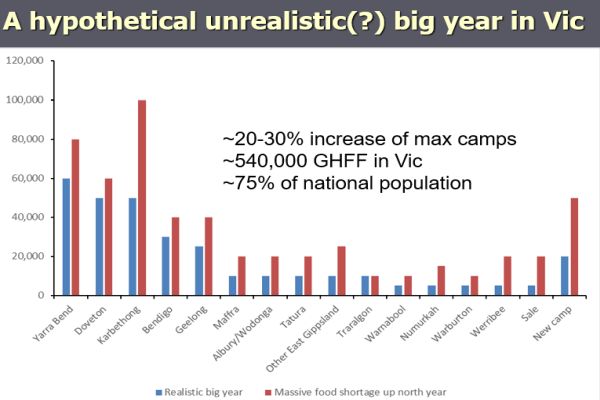

Rodney provided a snap-shot of flying-fox population dynamics in Victoria. He pointed out that major fluctuations in the size of the population in Victoria tends to correspond to adverse climatic conditions in northern habitats which can result in a food shortage in those areas, driving flying-foxes into Victoria.

Prior to the 1980’s there were some camps in East Gippsland but by the mid 1980’s the numbers were increasing at Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne. In 2003 there were around 30,000 flying-foxes which prompted relocation to Yarra Bend, at this time new colonies formed at Geelong, Warrnambool and Bairnsdale. Between 2010 to present there has been a steady increase in the number of camps around Victoria.

Rodney highlighted that the GHFF is highly mobile animal. He spoke about research involving satellite tracking of flying-foxes which showed significant movement of 2000km from Gippsland to northern Australia. Through research it is now understood that flying-foxes are moving around between all the camps all the time.

View video of satellite tracking in research paper; Welbergen, J.A., Meade, J., Field, H. et al. Extreme mobility of the world’s largest flying mammals creates key challenges for management and conservation. BMC Biol 18, 101 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00829-w

Key points from questions

Research has shown there is about a 15% chance that a GHFF will change colonies on a day-to-day basis.

Bioclimatic modelling could help in predicting the movement of the GHFF.

Bureau of Meteorology rain radar data has been used to track flying-fox numbers.

When feeding on nectar and pollen they can distribute pollen over vast distances aiding the genetic diversity of forest plants. Seeds are also dispersed throughout the forest in droppings which helps support forest diversity and renewal.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Living with flying-foxes in Victoria

Dr Leila Brook - Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

Leila acknowledged Traditional Owners of lands where she presented from and paid her respect to First Nations People and their connection to Country and wildlife.

The Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services team

Leila outlined the main role of the team, which is to provide non-regulatory advice to the community and stakeholders in relation to wildlife issues and support people to live with wildlife. The team also provides support for land managers dealing with flying-fox camps by providing advice on management actions and support the species as well.

How we view flying-foxes

Living with flying-foxes

Leila spoke about the types of conflicts which can arise when large numbers of flying-foxes appear rapidly. Towns and cities often provide suitable habitat, climate and foraging resources which are attractive to flying-foxes. Numbers can increase as food resources are plentiful but as the food resources diminish, the numbers of flying-foxes can reduce as they move to other areas in search of food.

The status of flying-foxes in Victoria

Leila pointed out that land managers or landowners are responsible for managing risks caused by wildlife on their land and there are a number of protections to consider:

- All flying-foxes in Victoria are protected wildlife under the Wildlife Act 1975

- Authorisation is required to wilfully disturb, harass or harm wildlife

- Grey-headed Flying-foxes are a listed vulnerable species: Victoria - Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 and nationally, under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

- The Commonwealth provides additional guidance for managing impacts to Grey-headed Flying-foxes

- The National Recovery Plan 2021 provides referral advice for land managers for management actions in camps that would not be a significant impact on the species

Nationally important camps are those with more than 10,000 flying-foxes or more than 2,500 every year over the last 10 years.

Leila pointed out that disturbance can be more detrimental when females are heavily pregnant or have young pups and in times extreme heat.

Data collection

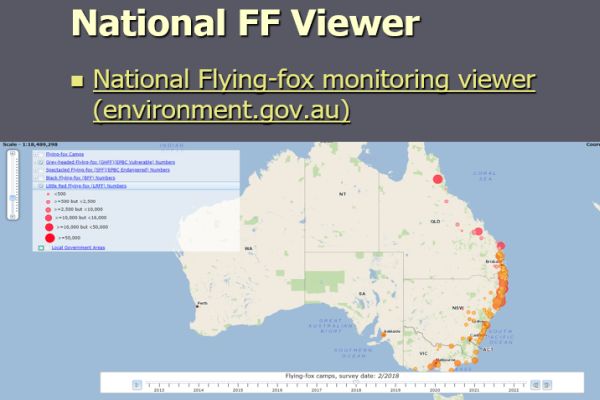

DEECA works with a network of stakeholders to gain information about flying-fox occurrence and movement which is provided to the National Flying-fox Monitoring Program. Quarterly counts using either static counts or fly counts are made to inform camp status and national estimates.

Records can also be submitted to the Victorian Biodiversity Atlas

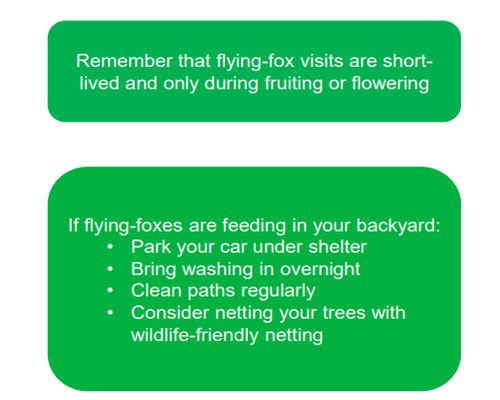

Flying-foxes in backyards

Leila highlighted that flying-foxes love to feed on trees in backyards containing nectar or fruit, but in most cases, they are only around for a short time as once the flowering or fruiting is over, they will move on.

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations 2019:

- Household fruit netting must be wildlife friendly

- Mesh size of 5x5 mm or less at full stretch

Tips for installing wildlife-friendly netting

- Use white netting which is more visible

- Fix netting tightly to the trunk or branch

- Consider using bags to net branches or clusters of fruit

- Remove nets once fruit is picked

- Check nets daily for wildlife

See more about Wildlife friendly netting

Disease

Leila explained that many species of wildlife carry disease, including flying-foxes which may be of concern to people. The main disease is Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV) which is rare in a healthy bat population, but more common in sick, injured or orphaned bats. The disease can be transmitted via saliva – bites, scratches so it is important to avoid bare skin contact with bats.

Hendra virus can be harmful to humans but is infected via horses, there is no evidence of direct transmission from bats. Horses can be vaccinated. There are no recorded cases in Victoria.

Flying-foxes and heat stress

Leila pointed out that flying-foxes are susceptible to increased stress under hot conditions, therefore addition stress caused by human disturbance can be very harmful. In the summer of 2019/20, it is estimated that around 5,000 flying-foxes perished from extreme heat.

DEECA is the lead control agency for responding to wildlife welfare issues. The Victorian Response Plan for heat stress was released in summer 2024 which directs a collaborative response with deployment of Victorian Government, Zoos Victoria and Wildlife Emergency Support Network (WESN) personnel including trained and experienced vets and volunteers.

Victorian Response Plan for heat stress in flying-foxes pdf

Tips for dealing with flying-foxes

- Do not touch or handle flying-foxes yourself, only people who are trained, vaccinated and wearing PPE should handle flying-foxes

- Don’t directly handle dead flying-foxes

- Call the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline 1800 675 888 if your pet has had significant contact with flying-foxes

- If you find an electrocuted flying-fox, call a wildlife rescuer or call your local power company or Council

- Don’t try to catch a sick or injured flying-fox – call a local wildlife rescuer instead, call DEECA 136 186

- Use DEECA’s Help for Injured Wildlife Tool to find a local contact – www.wildlife.vic.gov.au/hfiw

- Call a rescue service such as Wildlife Victoria (8400 7300)

Rehabilitation guidelines

Contact: Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services wildlife@delwp.vic.gov.au

Key points from questions

Although flying-foxes and Swift Parrots both feed on flowering trees providing nectar there is no research to indicate competition for food being a problem.

There are occasions when Grey-headed Flying-foxes and Little-red Flying-foxes co-occur for parts of the year in northern Victoria and East Gippsland but due to the highly mobile nature of the species the co-occurrence is often over a short timeframe. There are also some records of Little-red Flying-foxes occurring over short periods in Melbourne.

The more people that understand the behaviour of flying-foxes the better as people often have negative reaction to flying-foxes when they turn up without realising their occurrence is in response to food and generally for a short time only.

Local community talks can help dispel myths about the negative aspects of flying-foxes.

View recordings

The Ecology and Conservation of Victorian bats – Our Fascinating Creatures of the Night - Dr Lindy Lumsden - Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

A small bat with big challenges: Survival and seasonal movements of the critically endangered Southern Bent-wing Bat and implications for conservation - Dr Emmi van Harten – DEECA

The establishment, growth and fluctuations of Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Victoria: challenges for the community and managers - Dr Rodney van der Ree - Assoc Prof, National Technical Executive: Ecology School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne

Living with flying-foxes in Victoria - Dr Leila Brook - Statewide Wildlife Advisory Services, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

View notes from previous SWIFFT seminars