SWIFFT Seminar notes 22 October 2020

Native grasslands

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online via Microsoft Teams (159 participants) and streamed live via YouTube (107 views). SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Thanks to Michelle Butler who chaired the session from Ballarat and acknowledged the Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

A special thank you to Amos Atkinson who acknowledged the traditional lands covering the seminar across Victoria. Amos affirmed his people’s connection to Country and welcomed us to the home of the Dja Dja Wurrung people.

Key points summary

Is disturbance switching a useful restoration tool?

- Temperate grasslands have a disturbance requirement for the maintenance of species richness (doing nothing is not an option).

- Passive recovery of native species is slow, suggesting recovery is limited by agricultural land-use legacies.

- Active restoration in the form of seed addition + disturbance switching will likely improve restoration outcomes for endangered grasslands.

Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain

- Prior to European settlement grasslands were looked after for thousands of years by First Nations people.

- There is a relationship with the spiritual, social and physical perceptions for survival and knowledge of Country. Landscapes are living and breathing and part of Indigenous people’s well-being.

- By respectfully engaging traditional and western approaches in projects the outcomes will far exceed what could have otherwise been achieved.

Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape

- Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to Country means bringing people back and restoring the all the plants, animals, spiritual connections, cultural practices and the rights of traditional owners to make decisions about their land and their resources.

- A key enabler in the Self Determination Reform Strategy is to prioritise culture in programs such as Djandak Wi.

- The Dja Dja Wurrung have entered into a Recognition and Settlement Agreement 2013 with State of Victoria.

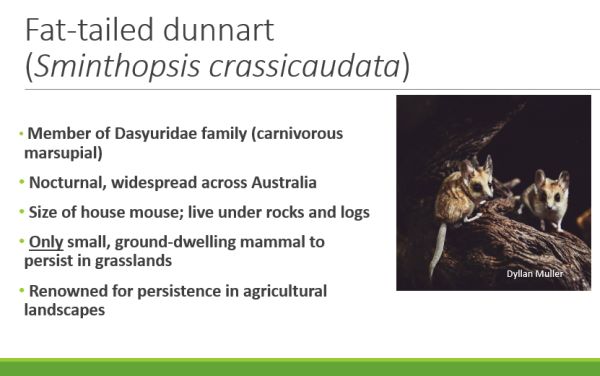

Fat-tailed Dunnarts of the Victorian grasslands

- Grasslands are among the most endangered ecosystems on the planet, with less than 1% of Victorian's grasslands remaining.

- The Fat-tailed Dunnart is the only small, ground-dwelling native mammal to persist in Victoria's grasslands.

- Not a single individual, scat or nest of a Fat-tailed Dunnart was found in one year of surveying from what was once Victoria’s stronghold for this species.

List of speakers and topics

Is disturbance switching a useful restoration tool? - Dr John Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution | La Trobe University

Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain - Chase Aghan - Project Officer (Forest, Fire and Parks) for Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Dr Brad Farmilo - Senior Scientist & Plant ecologist, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research (DELWP)

Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape - Nathan Wong, Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation and Amos Atkinson, Project Officer with Dja Dja Wurrung

Fat-tailed Dunnarts of the Victorian grasslands - Emily (Millie) Scicluna - PhD Candidate, La Trobe University

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Is disturbance switching a useful restoration tool?

Dr John Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution | La Trobe University

John’s presentation focused on disturbance switching from sheep grazing to fire in managing grassland and grassy woodlands.

John spoke about the commonality between the higher quality native grasslands, these are grasslands which have had some degree of burning over many decades, either without or very little grazing by stock.

Grassland ecology

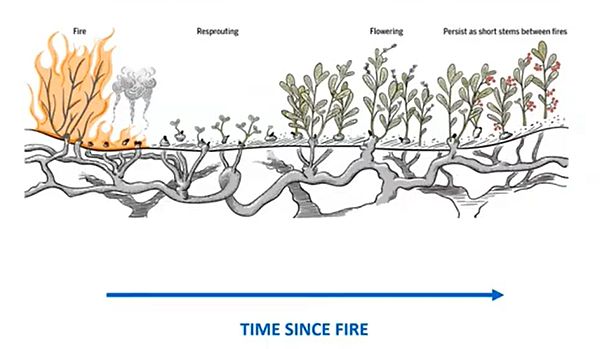

Regular burning is almost critical for the survival of many native grassland plants. Without burning, native species can be swamped by competitive grasses. After an Autumn fire event many of the native grassland species resprout and flower during the Spring and persist as short stems between fires.

Native grassland can respond to burning because many of the plants in native grasslands live below ground in the form of tubers and root stock. Source: J. Morgan presentation to SWIFFT.

An example of a native grassland species (Featherheads) Ptilotus macrocephalus which has the form of a below ground tree. Sparse leaf form and flowering stem (left) and an extensive below ground root system (right). Source: J. Morgan

Biomass removal

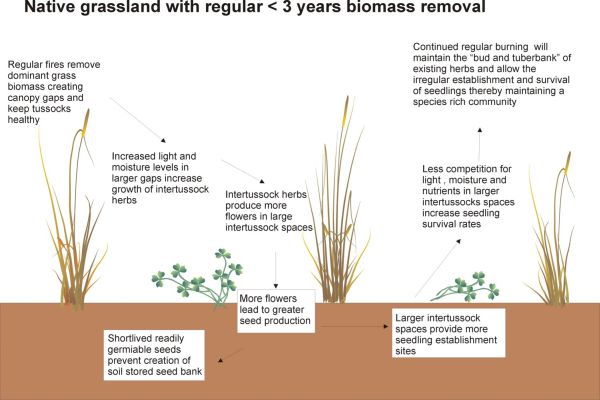

John spoke about the benefits of regular burning in reducing biomass and creating gaps between the grasses which promotes a diverse number of species to co-exist and flower on a regular basis. Prior to European settlement grassland biomass reduction occurred through indigenous burning and through digging and grazing by native fauna.

A summary of 30 years research - influences on native grasslands with a regular <3 year burning. Source: J. Morgan in presentation to SWIFFT.

Managing native grasslands across different land tenure

John made reference to the fact that many of the high-quality native grasslands are confined to linear roadside reserves which have benefited from regular burning with minimal stock grazing. The problem which needs to be addressed is management of native grasslands on private land and public land blocks, many of which have little or no history of being burnt.

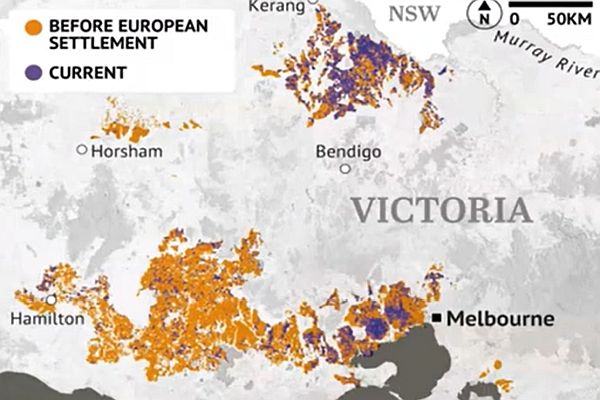

Native grasslands have had a significant reduction since European settlement. Many remnant grasslands have little or no history of being burnt since European settlement. Source: J. Morgan in presentation to SWIFFT.

Grassland management in Northern Victoria

John spoke about the management of remnant native grasslands in northern Victoria, particularly previous farm blocks which are now managed for conservation. John pointed out that many have had sheep grazing for over a Century which has led to a particular type of native grassland where many species have disappeared but some have benefited.

Management theory has often relied on maintaining the status quo when new grassland blocks are obtained. If a paddock has been grazed by sheep for decades yet still contains native grasses should we continue the same regime or should we try to improve the grassland by switching the way grazing is undertaken? Change the season or duration of grazing to try and promote more diversity of species.

Case studies on the Volcanic Plains

John referred to some of the long-running research projrcts on the Volcanic Plains near Birregurra, Darlington and Hamilton which looked at switching grazing regimes to determine if gains could be made to improve native grasslands.

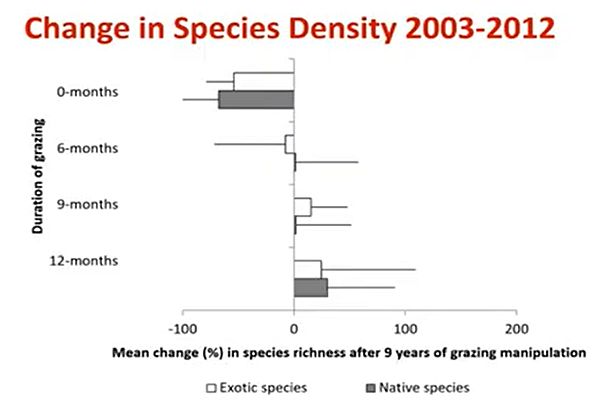

Changing the duration of grazing

The above graph depicts a grassland which has been grazed for over 100 years and has been part of an experiment where the grazing duration has been manipulated.

No grazing = negative outcomes for both native and exotic species.

6 months, 9 month and 12 months grazing = no significant change

Overall, experimenting with different grazing regimes has not been proven to provide better outcomes for grassland conservation. Source: J. Morgan in presentation to SWIFFT.

The need to improve native grasslands

John spoke about the need to actually improve grasslands and restore species like grassland daisies and grassland orchids. Clearly, just changing the duration of grazing does not lead to substantially better outcomes. Switching disturbance from sheep grazing to other forms of disturbance has been the subject of more recent research. Switching from sheep grazing to fire or slashing or other means.

Case study – Wannon Water Reserve

John spoke about research which involved shifting from sheep grazing to burning. The study site has been grazed for over 100 years and although still containing some native grasses many of the species have disappeared. Trials of Autumn burning have been carried out on an annual basis and a biannual basis since 2012. A series of permanent monitoring plots were established at the start of the burning trial program.

John pointed out that many of the species, including some endangered species are now more obvious at the site but he uses two measures to determine if the grassland is getting better, 1. Native species richness and 2. Native species cover.

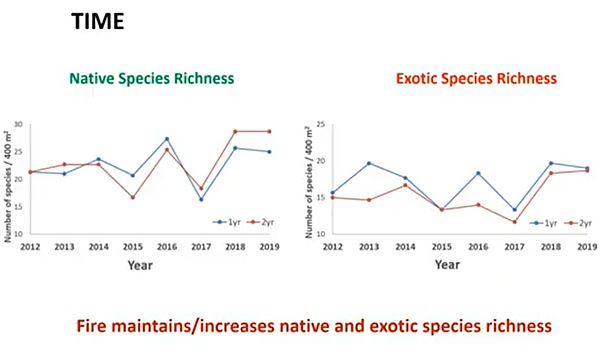

Species richness

Eight years of data on species richness from annually burnt grasslands (blue) and biannually burnt (red). John emphasised climatic events can also have a significant bearing on grassland condition, e.g. 207 - 2018. Burning has had little impact on driving exotic species down. Source: J. Morgan in presentation to SWIFFT.

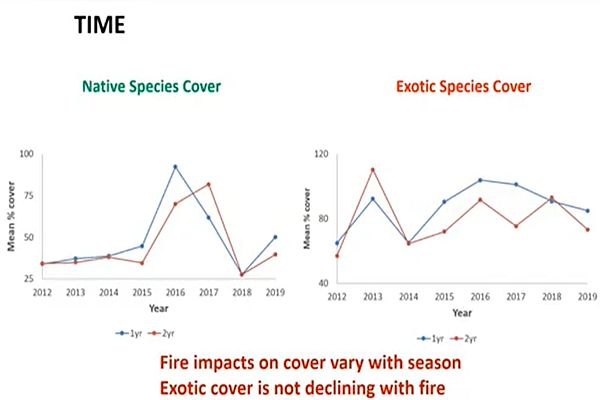

Species cover

There is no clear outcome which indicates native species cover has improved. There was up to a 20% increase in native species cover after 4 years but seasonal climate variability has a greater influence. Native species cover does not provide the full picture as an increase in cover may be due to one species. There is no clear indication that exotic species cover has declined due to the burning regime. Source: J. Morgan in presentation to SWIFFT.

Combining the results from species richness and species cover it becomes apparent that seasonal climate variability and the timing of rainfall plays a major role. Switching disturbance regimes does not yield immediate change, it is a slow a long-term process.

Analysis

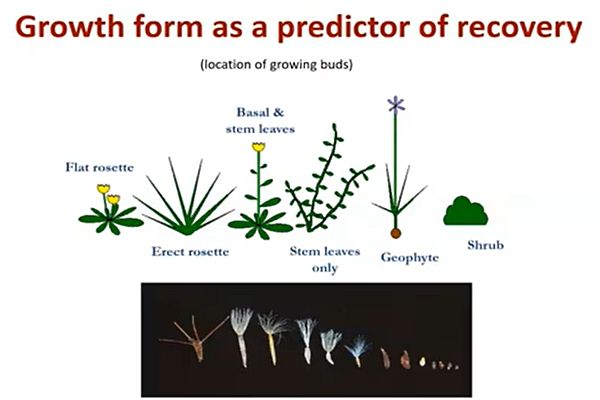

John spoke about some of the reasons why more species did not benefit from the burning regime. With species being lost due to long-term historic grazing the upright plants have most likely been wiped out and the soil seed bank lost.

After 100 years of grazing the stem leaf only type of plants and shrubs would have been wiped out. The main plant form surviving would be the flat rosette form plants.

Many of the seeds of grassland species don’t persist long in the soil. E.g. seed from grassland daisies only last have a maximum of about 5 years.

Positive outcomes when applying seed

John referred to research now published in Restoration Ecology; Land‐use legacies limit the effectiveness of switches in disturbance type to restore endangered grasslands. Jodi N. Price Nick L. Schultz Joshua A. Hodges Michael A. Cleland John W. Morgan First published: 16 August 2020 https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13271

We found mostly no change in native and exotic species richness when management changed from stock grazing to fire (at least in the short term ≤10 years). Positive outcomes for other disturbance shifts (grazing → mowing, or cultivation → grazing) occurred when the disturbance type was accompanied by seed addition, or in landscapes where dispersal from nearby remnant sites was possible.

Implications for grassland management

Learnings from 10 years of disturbance switching research at Dunkeld.

- Temperate grasslands have a disturbance requirement for the maintenance of species richness (doing nothing is not an option).

- Passive recovery of native species is slow suggesting recovery is limited by agricultural land-use legacies.

- Active restoration in the form of seed addition + disturbance switching will likely improve restoration outcomes for endangered grasslands.

Key points from questions

The availability of seed is slowly improving, the more people wanting to undertake grassland restoration using seed will help create a market.

Improving connectivity of native grassland throughout the landscape is the missing link in restoration.

Improving management by undertaking disturbance switching in the larger blocks is important as they will form the refuges of the future.

There has been a loss of small native mammals in our grasslands. More work is required to understand the role they can play in restoring grasslands.

At sites which have established weed problems there is still an opportunity to improve remnant native grasslands.

Rabbits do not replace the digging effects of small mammals as they don’t create the same type of disturbance as the native species.

Native grasslands in cropping areas in northern Victoria can recover when cropping is removed, however the species diversity is significantly reduced. E.g. lilies are lost due to cropping. Lilies are one of the groups of species that would be targeted for reintroduction.

Scalping is better suited in situations where native species are absent.

At present there is no evidence that African Weed Orchid is impacting on native grasslands, whilst is best to remove it we need to focus on other more invasive species such as Phalaris and Onion Weed.

Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain

Chase Aghan - Project Officer (Forest, Fire and Parks) for Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation

Dr Brad Farmilo - Senior Scientist & Plant ecologist, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research (DELWP)

View a recording of the presentation made on the day or read the notes below.

Chase acknowledged the traditional owners of the lands covered by the seminar, Elder’s past and present and emerging leaders. He also acknowledged he was presenting on Wadawurrung Country.

Indigenous connection to grasslands

Chase provided an overview of what grasslands mean to Indigenous people. Grasslands hold very important values both culturally and ecologically in south-eastern Australia. Prior to European settlement grassland were looked after for thousands of years by first nations people, fire stick farming provided renewal of the grasslands which in turn provided food and resources that enabled sustained residence on the Victorian Volcanic Plain.

Following the onset of Colonial grazing, the wetlands, grasslands and woodlands of the Volcanic Plain became degraded and fragmented resulting in the displacement of Aboriginal people. With firestick farming gone the grasslands and the species they contained became further degraded and are now amongst Australia’s most threatened plant and animal communities.

Restoration of Natural Temperate Grasslands

Chase emphasised the importance of grassland restoration, to restore cultural values, ecological services and populations of threatened species. Restoration requires meaningful partnerships between traditional owners and land managers.

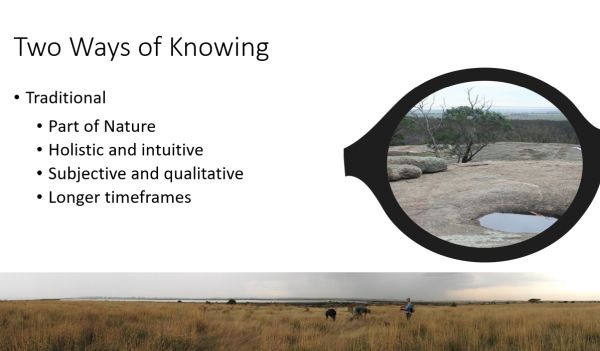

Chase discussed two ways of knowing natural landscapes:

- Traditional knowledge

- Western knowledge

By working together, the two approaches can improve natural vegetation and health of country.

Traditional knowledge

Traditional knowledge focuses on the aesthetics of an area's cultural landscape, seasons, changing climate and patters in nature. There is a relationship with the spiritual, social and physical perceptions for survival and knowledge of Country. Landscapes are living and breathing and part of Indigenous people’s well-being. Traditional knowledge and practices have been passed down through many generations to elders and have been relearned in recent times.

Looking through an indigenous lens. The continuation and obligation to care for country is vital in many aspects of traditional knowledge.

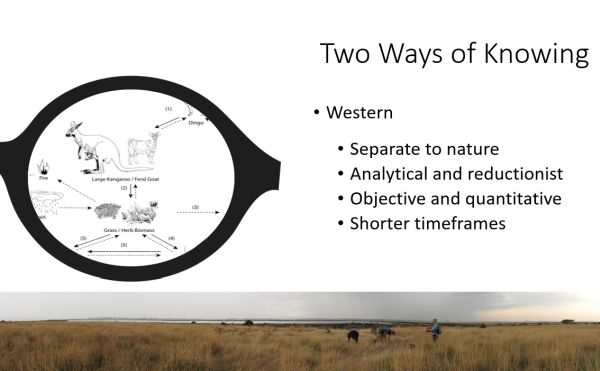

Western knowledge

Western science or knowledge has had a major influence on how country is managed. It relies on analysis of components of the ecosystem and takes a more objective and quantitative approach. The transfer of information is more academic and literate.

Combining Traditional and Western Knowledge

Chase spoke about the benefits of combining traditional and western approaches in decision making to help recover biodiversity loss in our grasslands. There have been many cases where traditional owners have not been consulted. Chase hopes that by respectfully engaging traditional and western approaches in projects the outcomes will far exceed what could have otherwise been achieved. Some of key benefits:

- Provides a holistic view

- Biodiversity recovery

- Policy awareness

- Can inform decisions

- Obligations to care for Country

- Apply indigenous culture through song, story, fire and other practices

- Western knowledge to aid in recovery

- Starting conversations

- Form great respectful partnerships

Chase referred to the difficulties in analysing one form of knowledge using the criteria of another. He referred to a paper Western science and traditional knowledge Despite their variations, different forms of knowledge can learn from each other. Fulvio Mazzocchi EMBO Reports Vol. 7 Issue 5, 1 May 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400693

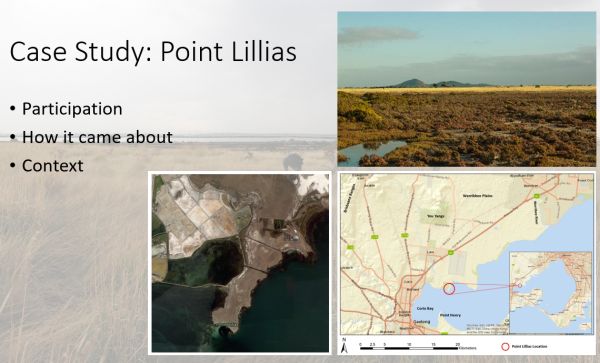

Point Lillias case study

The management of Pt Lillias grasslands has been a good example of how collaboration between traditional and western approaches can be applied. A grassland vegetation monitoring program has been established to inform management of the grasslands. Key partners in the process include; Arthur Rylah Institute, Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, Blue Carbon Lab., Corangamite CMA, Parks Victoria, Coastcare Victoria and Heritage Insights.

The Point Lillias project is a component of the Victorian Wetland Restoration Project and undertaken with the intentions of supporting Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation in managing country at Point Lillias.

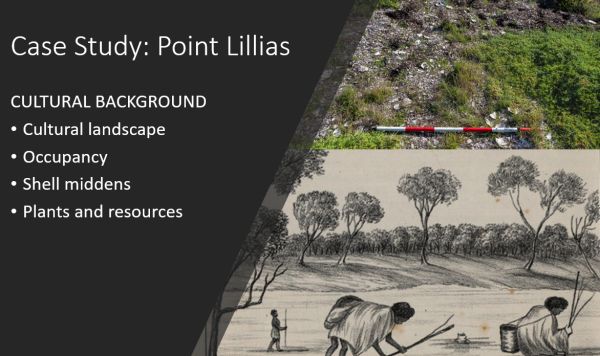

Pre-Colonial times the Point Lillias area was occupied by the Wadawurrung people.

Brad Farmilo from ARI continued with the presentation

Brad acknowledged traditional owners. He spoke about the ecological aspects of Point Lillias which is mostly comprised of a Coastal Tussock Grassland:

- Grasses - Spear and Wallaby Grass

- Wildflowers - Flax-lily, Bind-weed, Tiny Star

- Structure - High Biomass

- Threats - Perennial and Annual grasses, Artichoke Thistle

Project Objectives

- Reduce the cover of high threat weeds

- Maintain the integrity of cultural sites

- Promote native species recovery

Proposed outcomes from the case study

- Traditional Owners and Scientists working together

- Identify values and threats at Point Lillias grassland

- Design a grassland vegetation monitoring protocol (reflects two-ways of knowing) to inform grassland management and restore the health of Country.

Brad spoke about the process of combining two ways of thinking to look at and explore different perspectives on:

- Values

- Native plant species abundance

- Wildflowers

- Fauna habitat

- Native species diversity

- Cultural practices

- Threats

- Rabbits

- Weeds (grassy and herbaceous)

Brad felt the discussions on the above points were really valuable and helped to improve the knowledge and understanding of everyone involved reflecting the ‘two ways of knowing’.

Brad felt that by adopting the ‘two way thinking’ and communicating concept the model used in this case study will help others bridge the gap between traditional and western knowledge.

Key points from questions

The process of ‘two way thinking’ and knowledge sharing can be enhanced by spending time together on country in a safe and collaborative environment.

The ‘two way thinking’ approach can be adopted on private land and linear reserves. There is a lot of scope to have landholders share their view and values in the process.

Traditional owner vegetation site assessment tends to look at plant structure (native and exotic) and the threats.

Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape

Nathan Wong, Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation

Amos Atkinson, Project Officer with Dja Dja Wurrung - bringing back Traditional Ecological Knowledge to landscapes to heal country and heal the people using fire.

Amos paid his respect to the traditional owners and all the traditional lands covered by the seminar, he acknowledged all the Elders, past and present and emerging.

The need to act now

Amos provided an introduction by talking about his learnings related to fire and the cultural knowledge passed on to him from working with traditional fire practitioners around Australia. A key aspect in cultural burning is the bring of communities together and putting people back into the landscape.

Amos has an interest in understanding what landscapes were like prior to European settlement and how Indigenous people lived on the grasslands. He emphasised the need to act now as it will take many years for the country to heal. He is very concerned that future generations should not inherit a damaged landscape.

Introductory video - Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to Country.

What it means to return Dja Dja Wurrung to country

Nathan spoke about what it means to return Dja Dja Wurrung to country. As well as bringing people back it is about restoring the all the plants, animals, spiritual connections, cultural practices and the rights of traditional owners to make decisions about their land and their resources. The Dja Dja Wurrung need to be able to make decisions about where, when, how and why fire is applied to grassy landscapes on Dja Dja Wurrung country.

Dhelkunya Dja (Healing country)

Nathan provided an overview of how cultural practices and ceremony were taken away following colonisation. After the traditional use of fire was removed from landscape it was the start of decline for native grasslands.

Dja Dja Wurrung are now starting to manage the grassy ecosystems through either status quo (some form of grazing) and introducing ecological fire to the landscape. The next step is to apply cultural practice to the landscape, bring back the knowledge, ceremony and cultural practice as well as the people, plants, animals and spirits.

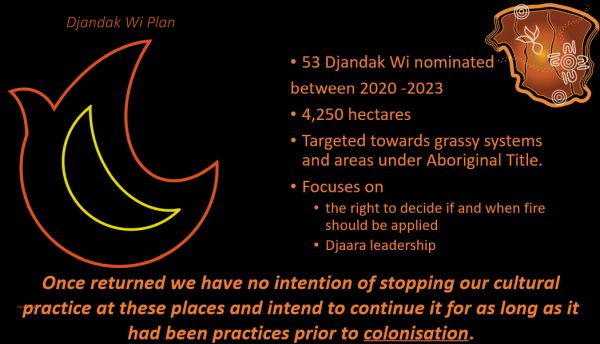

Djandak Wi objectives

Amos spoke about the objectives:

- To increase the presence and leadership of Djaara on Country

- To improve the health of the grassy understory

- To increase the knowledge and understanding of Country by Dja Dja Wurrung

Objective 1. Increasing the presence of Djaara on Country

Nathan explained the process for restoring fire back to landscape. The aim is to have 90% of the Djaara people present on the burn day. There is also a willingness to have other traditional owner groups participate. It is hoped that the burn OIC will be within Djandak and Dja Dja Wurrung soon, it will help ensure the burns are undertaken for the right reasons at the right conditions and time by the right people.

Objective 2. Improve the health of the grassy understory

Nathan spoke about improving the grasslands for plants and animals but also ensuring grasslands are a source of food and materials. The need to build an increased understanding of how animal and plants are connected to country and identifying species which should not be present is also important.

Objective 3. Increase the knowledge and understanding of Country by Dja Dja Wurrung

There is a need to increase the knowledge of cultural heritage by undertaking surveys and recording sites. There is also a need to understand and identify if the right plants and animals are in the right places across the landscape.

Self-Determination Strategy

Nathan spoke about the Self-Determination Strategy which has come out through the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP). A key enabler is to prioritise culture in programs such as Djandak Wi. The western system is there to drive and enable rather than determine. Nathan felt the Self-Determination strategy is a good document, well worth reading.

Recognition and Settlement Agreement in 2013

Nathan also spoke abut the Recognition and Settlement Agreement in 2013 that Dja Dja Wurrung have entered into. The document is within the Victorian State Government framework. Nathan felt it is a strong enabling document which sets rights and obligations in managing land and systems.

Djandak Wi plan

Projects

Nathan discussed some off the healing Country activities in northern Victoria. He pointed out there are numerous sites where planning and activities are being undertaken. Two examples are; water restoration at Tang Tang Swamp and applying fire to the reserve though a series of incremental burns meaning no more than 10-15% of the area ever gets burnt on a particular day. Management of Hunter Flora Reserve, which is a significant site in northern Victoria.

Nathan spoke about having a more inclusive gender role into the future. Amos added it is also great to see a diversity of age groups represented in the process. Adding ceremony to the restoration process will be a focus into the future and help people to connect with the cultural values of the grasslands.

Key points from questions

Murrup means Spirit.

Mother earth is god to the Dja Dja Wurrung and it must be looked after. The Dja Dja Wurrung are very spiritual people which they gain from their connection to Country.

This is a Djandak logo which depicts an image of Country (the Registered Aboriginal Parties RAP boundary area). It also depicts the significance of the Yam Daisy, an important food source. Special places are also included in the logo.

Fat-tailed Dunnarts of the Victorian grasslands

Emily (Millie) Scicluna - PhD Candidate, La Trobe University

Emily is a 3rd year a PhD candidate at La Trobe University working in reintroduction biology, with her study species being the Fat-tailed Dunnart.

Emily introduced her presentation by highlighting the anthropogenic disturbances in the landscape such as modification and destruction of habitat, as well as the introduction of both invasive predators and competitors which are major drivers in the endangerment of Australian mammals.

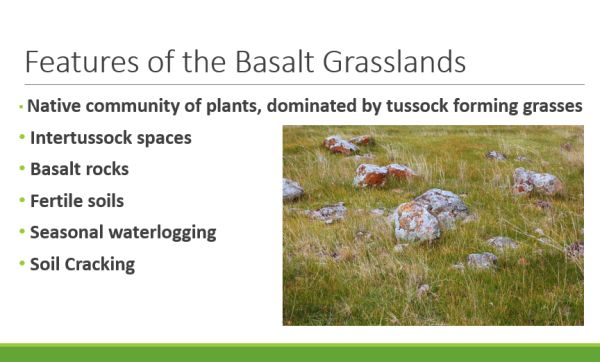

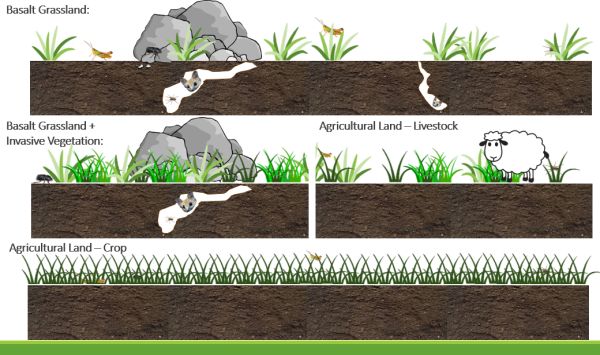

Basalt grasslands overview

Emily pointed out that grasslands are among the most endangered ecosystems on the planet, with <1% of Victorian grasslands remaining. Although introduced predators are a factor in species decline the overwhelming issue is the loss of suitable habitat.

Emily spoke about the severe loss of native mammals on the grasslands. Since European settlement there has been an extinction of 30 Australian mammals, 26 of these were either entirely dependent or in some way utilised Victorian grasslands. The concerning issue is that many of the threats remain and declines in species populations are continuing to occur.

The Fat-tailed Dunnart

Two sub-species of Fat-tailed Dunnart are recognised:

- Sminthopsis crassicaudata crassicaudata - predominantly occupies grasslands (Victoria, southern NSW and south-east SA)

- Sminthopsis crassicaudata centralis - occupies desert areas in central Australia extending to WA.

Emily pointed out her studies focus on Sminthopsis crassicaudata crassicaudata which occurs in Victoria. Although the Fat-tailed Dunnart is regarded as being Least Concern (IUCN Red List) and Near Threatened (Advisory List of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria), unfortunately, the current conservation classifications do not take the two sub-species into account.

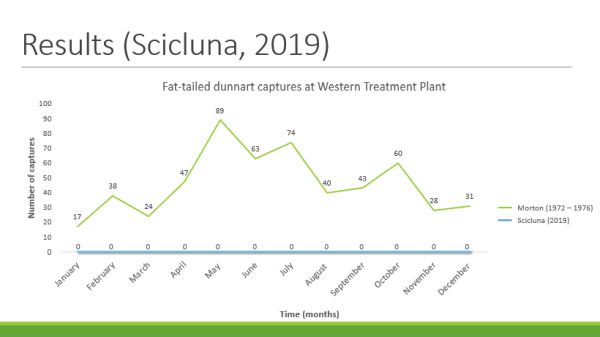

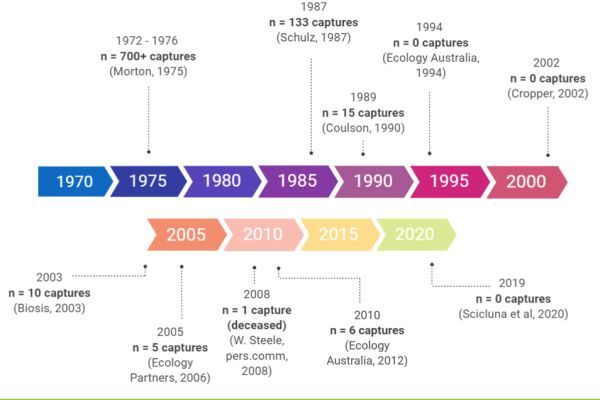

Emily is concerned the Fat-tailed Dunnart is incorrectly classified im Victoria as the last targeted surveys for this species occurred in Victoria by Steve Morton in 1972 - 1976. Norton's surveys were at the site of the largest known population of this species, being the Western Treatment Plant, Werribee. Morton surveyed 4 sites at the treatment plant area and recorded 700 fat-tailed dunnart captures at these 4 sites after surveying monthly for 4 years.

Re-surveying old sites

Emily discussed how she went about setting up a new 12 months survey program at Morton’s old survey sites at the Western Treatment Plant, Werribee. Unfortunately, two of Morton’s four sites have been leased for agriculture and the landscape stripped of rocks, another site was cleared for development. One of Morten’s main sites still remained. Emily was able to follow Morton’s survey methods and also add the use of roof tiles to increase her chances of finding dunnarts. Emily undertook monthly surveys of 5 transects of roof tiles each 1 km long totalling 180 roof tiles and 250 rocks which were identified in Morton’s previous surveys (total over 12 months survey = 3,000 rocks and 2,160 tiles monitored).

Average number of Fat-tailed Dunnarts per month (Morton – Green), Scicluna (Blue)

Not a single individual, scat or nest of a Fat-tailed Dunnart was found in one year of surveying from what was once Victoria’s stronghold for this species.

Decline of the Fat-tailed Dunnart

Emily provided an overview of known surveys since Morton’s targeted surveys 1972-1976. As far as she can determine there have been only incidental records of this species and records from known surveys show a severe decline in the species. The last time any Fat-tailed Dunnart's were recorded at Werribee was in 2010 with 6 captures.

Owl pellet survey method

Owl pellets can be analysed to determine the presence of a prey species such as the Fat-tailed Dunnart. In 1972 -73 Morton collected owl pellets from roosts near his main study site at Werribee. Dunnarts made up 1.3% of all prey items. From 1979-80 Baker-Gabb looked at owl pellets from the same site and found dunnarts made up 2% of all prey items. From 2008 to 2012, Steele & Brunner from Melbourne Water collected owl pellets from the same roosts as the previous surveys, and found absolutely no traces of fat-tailed dunnart in any of them.

Conclusion

Review of conservation status

Emily has undertaken a number of enquiries with Commonwealth, State and International agencies to see if the conservation status can be reviewed. At present the only way this can be done if there are two consecutive years of survey data across the entire species range. This type of survey effort is beyond her capacity. Emily has had discussions with DELWP to see if the conservation status on Victoria’s Threatened Fauna Advisory List can be updated.

Dunnart ecosystem

Revisiting land use practices at the Werribee study site

Emily undertook research into the changes which may have occurred at the Western Treatment Plant study site. Somewhere between 2000 and 2004 two of the sites were leased, mown for grass and levelled between 2006 and 2009. Then in 2012 the site was ploughed, and in 2013 grain silos were constructed, but the last record of fat-tailed dunnarts was in 2010 so it was in fact before these habitats were flattened.

Emily emphasised that the same mistakes which occurred at the Western Treatment plant are being made across Victoria. We are removing habitat without realising this species is even there, and that is a huge problem for our dunnart friends.

Further considerations from Emily’s research:

- Revisiting historic surveys is important

- It is imperative for the survival of our species to ensure conservation listings are up to-date

- Now is the time to view Fat-tailed Dunnarts as two separate subspecies, with very different threats

- We need to ensure that the limited resources we do have, go to the right places

- Predicted land use change trending towards cropping in Victoria will have major implications for dunnarts

Key points from questions

There is a distinct genetic difference between the two sub-species of Fat-tailed Dunnarts (Cooper 2000) https://www.publish.csiro.au/ZO/ZO00014

Unfortunately questions were restricted due to time constrains.

See also: Fat-tailed Dunnart species page on SWIFFT

Update: The Fat-tailed Dunnart was listed as Vulnerable on the FFG Threatened List - June 2023.

See also:

Notes from SWIFFT video conference Native grasslands - 14 November 2007 - pdf

Recording of seminar - Woorndoo Community Day - Celebrating restored grasslands

Previous SWIFFT Seminars with Indigenous Cultural themes

- Cultural Protocols, Threatened Species and Traditional Knowledge

- Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain

- Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape

- Gunditjmara fish, mussels & crayfish

- Indigenous knowledge of ecology

- Indigenous Fire Workshop, Cape York

- Aboriginal waterway assessments

- Barapa Barapa Water for Country project