SWIFFT Seminar notes 23 May 2024

Unfolding trends in conservation

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 221 participants via Microsoft Teams. SWIFFT wishes to thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Also, thanks to Professor Sarah Bekessy, RMIT University, who chaired the session and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

This seminar helped to raise awareness of emerging trends in biodiversity conservation across, Indigenous education, Australian Government initiatives, private land conservation and new ways of thinking about how we deal with development projects.

Key points summary

Unfolding trends in Indigenous science and biodiversity education

- There is a need to expand the development of holistic curriculums for primary schools, which includes traditional knowledges by working with local Aboriginal groups, thus creating a connection between the school and local Aboriginal peoples.

- There needs to be a mindset shift in education, from having to cover First Nations topics to wanting to lead education through a First Nations lens which yield a positive long-lasting impact.

- There needs to be a funding shift directed towards specific funding to encourage First Nations people to learn about conservation through a First Nations lens and share this information across the broader society.

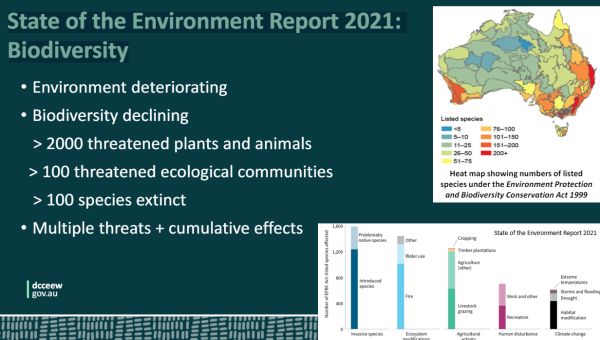

Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032

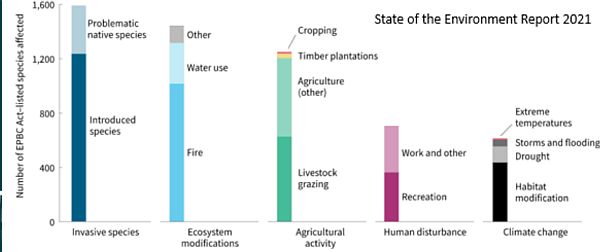

- The State of the Environment Report 2021 indicated a deteriorating environment with biodiversity in decline. Over 2,000 of Australia’s native species are threatened with extinction. More than 100 ecological communities are threatened and in excess of 100 species that have gone extinct in Australia.

- The Threatened Species Commissioner has a national focus to Australia’s threatened species and has connections with other government departments, agencies and stakeholders to facilitate science, action, and partnerships.

- The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 has a national focus and is a key document to guide the work of threatened species recovery across Australia.

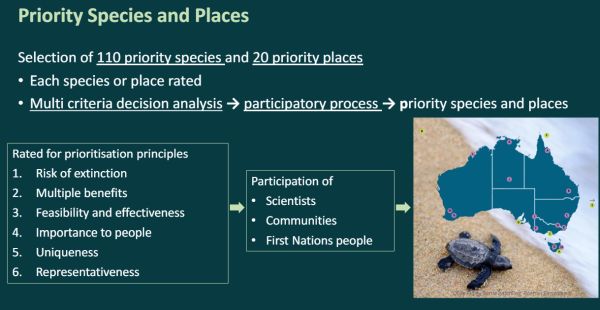

- Overarching Objectives of the Threatened Species Action Plan include; no new extinctions, 30% land mass conserved, improved trajectory for 110 priority species over the next 5 years, on track for improved condition of 20 priority places over the next 5 years.

Australian Land Conservation Alliance

- The Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA) is a peak body that represents organisations working to protect, manage and restore nature on privately managed land across Australia.

- ALCA is an independent, non-government organisation that leads, organises, advocates for, and acts on behalf of members with a focus on sector development, policy and regulation, investment, and people.

- ALCA forms a critical national voice for nature conservation, building nature understanding and helping to move nature up public, private and philanthropic agendas.

- With around 60% of Australia being private land there is a significant opportunity for private land to contribute to Australia’s national reserve system, alongside public protected areas and Indigenous protected areas.

Unfolding trends in conservation - the shift towards onsets and being nature positive

- We need to shift policies and legislation from nature being a problem in developments to nature being a positive aspect of development.

- There needs to be a transformative change in the way we view and care for nature if we are to meet the big global goals of realising net positive to nature by 2030 and full recovery by 2050.

- There is a role for government’s to lead and implement conservation incentives and legislation as agents for social change, helping to normalise behaviours and embedding nature values in society.

- Rather than continue with the same development paradigm which separates people from nature we need to embrace a new way of thinking which retains, enhances, protects and restores nature at the same place and time as development activity – Onsets.

List of topics and speakers

- Unfolding trends in Indigenous science and biodiversity education - Natasha Ward, Research Officer and Educator RMIT University

- The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 - Dr Fiona Fraser, Threatened Species Commissioner - Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

- The Australian Land Conservation Alliance - Dr Jody Gunn, CEO, Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA)

- Unfolding trends in conservation - the shift towards onsets and being nature positive - Professor Sarah Bekessy, RMIT University

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Unfolding trends in Indigenous science and biodiversity education

Natasha Ward, Research Officer and Educator RMIT University

This is a summary of key points from Natasha’s presentation.

There is a need to expand the development of holistic curriculums for primary schools which includes traditional knowledges by working with local Aboriginal groups, thus creating a connection between the school and local Aboriginal peoples.

Totemic species are particular plants or animals that are gifted by a parent or elder to either an individual or group, they can be an effective lens for engaging students with Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity conservation

Developing resources to support First Nations conservation education would help in expanding programs across more schools as teachers would have a starting point without having to create a project on their own. It is difficult for teachers to initiate funding with limited resources available.

There needs to be a mindset shift in education, from having to cover First Nations topics to wanting to have projects that have a positive long-lasting impact on First nations people.

Incorporating Indigenous rangers into education programs is very worthwhile as it provides a more practical on-ground perspective to First Nations students as well as being a role model, students can see a career pathway into conservation.

Having Indigenous rangers involved in education also helps non-indigenous students to interact with Indigenous rangers, helping to break down negative stereotypes and better understand conservation through an Indigenous lens.

More information: “Totemic species” can be an effective lens for engaging students with Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity conservation. First published: 06 March 2023.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032

Dr Fiona Fraser, Threatened Species Commissioner - Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

Fiona acknowledged the Ngunnawal people as the Traditional Custodians of the Canberra region from where she presented and all Indigenous people participating in the seminar.

Australia’s biodiversity

Fiona pointed out that Australia is one of the megadiverse countries in the world, with nearly 600,000 native species, many evolutionarily distinct. There is a high number of endemic species, for example 85% of native plants being endemic to Australia. Australia is also home to half the world’s marsupials.

Australia contains very diverse biomes, encompassing tropical, temperate and arid regions.

State of the Environment Report 2021: Biodiversity

Fiona spoke about the State of the Environment Report 2021, which is a statutory requirement of the Australian Government to produce an independent State of the Environment Report every 6 years which has now been ramped up to every 2 years.

Fiona highlighted the 2021 report was the first report in which every chapter was co-authored with a First Nations author, an arrangement that will continue into the future.

Australia state of the Environment Report 2021

Role of the Australian Government

Fiona outlined the role of the Australian Government in threatened species conservation. The Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act 1999) provides regulatory protection for threatened plants, animals and ecological communities. The EBPC Act also recognises key threatening processes. Fiona highlighted that major reforms to environmental law are now underway.

Fiona emphasised that having environmental law is not the only mechanism for protecting threatened species. A number of proactive initiatives include:

- Investment in on-ground action and research (e.g. Natural Heritage Trust, Saving Native Species program and NESP)

- Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032

- Management of Commonwealth managed areas (e.g. National Parks)

- Partnerships and collaborations with Staes and Territories (Federated system)

- Collaboration with the broader community and management agencies involved with threatened species across the spectrum.

Office of the Threatened Species Commissioner

The Threatened Species Commissioner has a national focus to Australia’s threatened species and has connections with other government departments, agencies and stakeholders to facilitate science, action, and partnerships.

The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 has a national focus and is a key document to guide the work of threatened species recovery across Australia.

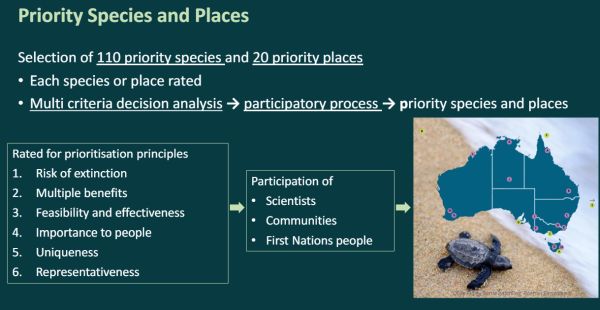

Threatened Species Action Plan

Overarching Objectives

- No new extinctions

- 30% land mass conserved

- Improved trajectory for 110 priority species by 2027

- Improved condition for 20 priority places by 2027

Fiona pointed out that the 4 main overarching objectives are underpinned by 22 measurable targets that relate to threatened species, habitat, places, abating threat, creating insurance populations, engaging with Aboriginal & Torress Strait Islander peoples, planning, research and community engagement through Citizen Science.

Priority species

Fiona provided an overview of the 110 priority species which span all taxonomic groups. She also showed how the ‘Known’ and ‘likely’ distribution of priority species was well distributed across Australia and pointed out that in-situ conservation efforts for one species is likely to deliver benefits for other species when it comes to threat abatement.

Fiona showed the full list of priority species in Australia and highlighted the species which occur in Victoria. Table below modified from presentation showing priority species under the Threatened Species Plan 2021-2032 which occur in Victoria.

Table of priority species adapted from the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2023

Priority Birds (22 species) 10 in Victoria

- Australasian Bittern

- Black-eared Miner

- Eastern Curlew

- Hooded Plover (eastern)

- Malleefowl

- Orange-bellied Parrot

- Plains-wanderer

- Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo (SE)

- Regent Honeyeater

- Swift Parrot

Priority Mammals (21 species) - 7 in Victoria

- Australian Sea-lion

- Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby

- Eastern Quoll

- Leadbeater's Possum

- Mountain Pygmy-possum

- New Holland Mouse

- Southern Bent-wing Bat

Priority Fish (9 species) - 1 in Victoria

- Murray Hardyhead

Priority Invertebrates (11 species) - 3 in Victoria

- Eltham Copper Butterfly

- Giant Gippsland Earthworm

- Glenelg Freshwater Mussel

Priority Frogs (6 species) - 1 in Victoria

- Growling Grass Frog

Priority Reptiles (11 species) - 0 in Victoria

Priority Plants (30 species) - 3 in Victoria

- Adamson's Blown-grass

- Forked Spyridium

- Stiff Groundsel

Priority places

Fiona explained that identification of Priority Places provides an opportunity to not only focus on Threatened Ecological Communities but to also to deliver benefits to non-priority threatened species which are found in the area.

Fiona used the example of the Australian Alps Priority Place, which is home to 85 EPBC listed threatened species and Alpine sphagnum bogs and fens threatened ecological communities. The Australian Alps Priority Place faces threats from invasive species (e.g. horses, deer, pigs), climate change and fire. The Threatened Species Commissioner is currently working with key stakeholders to deliver the actions needed to achieve an improvement in condition of the Australian Alps Priority Place.

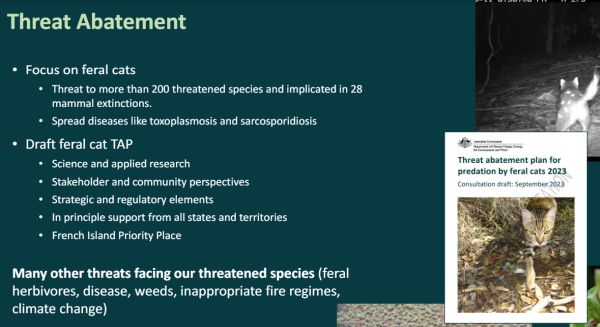

Threat abatement

The Threatened Species Action Plan deals with Threat abatement e.g. feral cats, foxes, myrtle rust, Fiona explained that threat abatement involves co-ordinated actions across states and territories and supporting strategic on-ground actions based on the best available science to ensure efforts have the most impact.

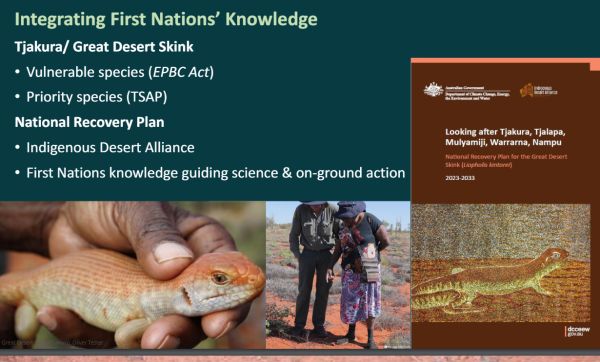

Integration of first nations

The Threatened Species Action Plan has a focus on the integration of First Nations’ knowledge and has targets to First Nations’ lead activities. Fiona used an example of how First Nations’ knowledge is being incorporated into EPBC Act recovery planning.

No new extinctions

The target of no new extinctions is an ambitious target but achievable with the right combination of resources and regulatory settings. The focus is not on funding species that have not been sighted for a number of years but rather applying resources to prevent a known species from tipping into an extinction event e.g. Grassland Earless Dragon.

Innovation and Research

There are a number of technological advancements in the detection of threatened species. The Action Plan covers improving access to data (e.g. standardised monitoring protocols, Biodiversity Data Repository, new Environment Information Australia)

The plan also includes investing in research e.g. National Environmental Science Program (NESP) as well as a target to develop new tools to mitigate impacts of broad-scale threats.

Fiona’s closing comments

We are at a critical point in time in the recovery of our threatened species. The challenge is enormous, but ambition and opportunity is high. The Australian Government has an important role to play – but cannot do this alone, conservation is everyone’s responsibility.

Key points from questions

There is around $550 million for threatened species under the Australian Government but in addition there is seperate funding for other environmental programs such as the National Heritage Trust funding and Urban rivers programs which also help threatened species.

The Threatened Species Action Plan provides a means of ensuring the funds are used effectively as possible by being directed to areas that can yield the best outcomes.

It is important to ensure a nationally consistent government approach to threat abatement across the Commonwealth, States and Territories.

There is a role for everyone in the community to play when it come to threatened species conservation from the way we live our lives to the way we raise awareness about biodiversity conservation issues.

Urban parks and gardens are not specifically included in the Action Plan, but in cases where threatened species occur in urban environments, they do form part of the recovery effort.

People can contribute to biodiversity conservation through planting native trees in their own backyard.

The Threatened species Commissioner works in co-operation with agriculture, particularly biosecurity in terms of invasive species which can impact on both agriculture and native species.

A large proportion of NHT funding is directed towards sustainable agriculture which is delivered through Landcare to establish benefits to agricultural production through establishment of native trees and wetlands.

Threatened Species Action Plan 2021-2032

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Emerging trends in biodiversity conservation across private land and the Australian Land Conservation Alliance

Dr Jody Gunn, CEO, Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA)

Jody acknowledged Traditional Owners past and present and the role they play in managing Country.

The Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA) is a peak body that represents organisations working to protect, manage and restore nature across privately managed land across Australia.

ALCA is an independent, non-government organisation that leads, organises, advocates for, and acts on behalf of members with a focus on sector development, policy and regulation, investment, and people.

ALCA forms a critical national voice for nature conservation building nature understanding and helping to move nature up public, private and philanthropic agendas.

Private land conservation

Jody spoke about the importance of private land conservation, which is home to almost half of Australia’s threatened species, contains some of Australia’s most threatened ecosystems and provides connectivity for biodiversity across the landscape.

There is a broad contribution of organisations and individuals involved in private land conservation across Australia. With around 60% of Australia being private land there is a significant opportunity for private land to contribute to Australia’s national reserve system, alongside public protected areas and Indigenous protected areas. Private land conservation contributes to the aim of achieving a national target of 30% of land and water protected by 2030.

At present there are more than 6,000 private landholders who are protecting biodiversity habitat in perpetuity across Australia and many thousands more who chose to undertake private land conservation without formal agreements.

Key slides from Jody's presentation

Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA)

Key Points from questions

Whilst there has been a rise in bequests through donations and charities only about 5% of the broader giving is directed towards climate and the environment.

Jody highlighted that Australian landholders love nature but they need help to protect and restore nature which ultimately delivers benefits to all Australians.

There is a need to provide improved support to landholders engaged in private land conservation such as:

- equitable tax treatment and incentives for conservation landholders.

- strong outreach and engagement to support landholders

- financial incentives

ALCA is involved in the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) financial disclosures forum as organisations are starting to think about the risks and dependencies on nature. More information https://tnfd.global/

ALCA has been trying to showcase projects where land conservation agreements hold firm against other competing land use, for example in Queensland there is a type of conservation covenant that protects the land from other uses including mining. ALCA is advocating that other state governments adopt a similar level of protection for land protection agreements. Policy Note: Enhanced Protection Conservation Covenants pdf

The meeting chat expressed a tremendous amount of support and appreciation for the advocacy role provided by the Australian Land Conservation Alliance.

ALCA's mailing list, sign up here

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Unfolding trends in conservation - the shift towards onsets and being nature positive

Professor Sarah Bekessy, RMIT University

Sarah focused her presentation on emerging trends in ‘offsets’ and the concept of investing in ‘nature positive’.

Sarah discussed how we need to shift policies and legislation from nature being a problem in developments to nature being a positive aspect of development. She felt that ‘nature positive’ is one of the most interesting unfolding trends in conservation in recent times. Nature positive is building on the fact that finally there appears to more recognition that nature has long lasting benefits to our everyday lives.

Changing the way, we live our lives

Sarah spoke about the need for transformative change in the way we view and care for nature if we are to meet the big global goals of realising net positive to nature by 2030 and full recovery by 2050.

Sarah pointed out that if we don’t want our future generations to inherit an environmental catastrophe, we need to re-think the way we do things such as building houses, extracting resources, the way we grow our food and deal with waste. We need to re-think our growth economy, there needs to be fundamental reorganisation across technology and social factors; business as usual is not an option.

Driving a nature positive change

Sarah highlighted the need for conservation incentives and legislation to be used as agents for social change, helping to normalise behaviours and embedding nature values in society.

Biodiversity offsets – a failure

Offsets are highly unlikely to achieve the nature positive outcomes that are required if we are to avoid further decline.

Sarah spoke about the premise of thinking it is ok to destroy nature if you pay the right price. This approach allows business as usual to carry on with cumulative ecological damage which has become normalised.

People value nature

Sarah discussed outcomes from surveys around the world and repeated survey in Australia which find people value nature. A recent survey conducted by the Biodiversity Council found 97% of people want more action to support Australian biodiversity conservation. Read more about Biodiversity Council survey.

Biodiversity Onsets

Rather than continue with the same development paradigm which separates people from nature, Shara highlighted a new way of thinking, to retain, enhance, protect and restore nature at the same place and time as development activity – Onsets.

Onsets can lead to social change as it establishes a norm that nature must be better off after development than beforehand and aligns with the universal value that nature should be protected.

Sarah pointed out that 97% of private land in Victorian land has been cleared so there is definitely a large area where onsets could be applied.

Sarah spoke about some examples of Onsets which involved turning developments into positive outcomes for nature. Sarah also spoke about opportunities for nature positive agriculture.

In regard to net zero energy developments, Sarah spoke about the conflict of developing windfarms whilst causing nature loss through land clearing or bird strike, particularly to threatened species. A more positive way of being nature positive would be to place solar farms on unproductive or degraded land and restore nature by planting an understory of threatened species of plants and grasses – create a nature positive solar farm. At present renewable energy projects are not required to be nature positive so there is definitely scope for innovation.

Direct and indirect impacts on biodiversity

Sahra discussed the need to look beyond the immediate impacts of development and consider both upstream and downstream impacts e.g. where materials are sourced, the level of resources are consumed and buying and selling of goods and services to other entities as part of development.

Sarha felt onsets are most suited to direct impacts but can be transportive across other sectors.

Onsets for community gains

There is a growing understanding of an expectation that development will deliver community gains. With increased uptake of biodiversity legislation to support net gain on site, the concept of onsets will be taken as a norm in developments.

Onsetting developments on-site can help prevent greenwashing associated with offsets that are often far away from the development, out of mind and not well evaluated.

Sarah felt onsets are the most transformative and desirable vision for future developments, one in which proponents have to be innovative and generate landscapes where communities gain from improved nature, which we all know is good for us.

Key points from questions

There are massive opportunities for onsets across the agricultural sector, in part because there has been so much degradation but also because there is a growing recognition that biodiversity is not necessarily incompatible with agricultural productivity.

If government ran with the concept of onsets there is every reason to believe that many industry sectors would welcome the opportunity to be nature positive. At present there appears to be a pent-up demand for many parts of industry, renewal energy and urban development sectors to be nature positive.

The Biodiversity Council was established as a science-based advocacy organisation to make the case for investment and action for biodiversity as it is what the community wants – yielding benefits for the economy, society and the environment. More about the Biodiversity Council.

Applying onsets to windfarm developments is possible but the actual siting of windfarms needs to take account of the clearing of native vegetation, which currently has offsets. Onsets would drive avoidance of vegetation removal in the first place. There is no reason why we can’t have renewable energy and biodiversity onsets. It is just that proponents are not asked to do so.

More information: RMIT Centre for Urban Research, Onsets not offsets for real biodiversity gains.

Previous SWIFFT Seminars with Indigenous Cultural themes

- Shifting attitudes and support for Cultural fire practices

- Cultural Protocols, Threatened Species and Traditional Knowledge

- Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain

- Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape

- Gunditjmara fish, mussels & crayfish

- Indigenous knowledge of ecology

- Indigenous Fire Workshop, Cape York

- Aboriginal waterway assessments

- Barapa Barapa Water for Country project