SWIFFT Seminar notes 23 July 2020

Urban ecology

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online via Microsoft Teams (153 participants) and streamed via YouTube (83 plays). SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Thanks also to Michelle Butler who acknowledged traditional owners and chaired the session from Ballarat.

Key points summary

Embedding ecology and biodiversity in urban parks

- At least 50% of the human population live in an urban landscape.

- Species response to urbanisation; pre-adapted to urban conditions, maladapted to urban conditions and lost due to migration or local extinction or adapt through natural selection response.

- In Melbourne, only about 4% of native vegetation remains.

- Ecology needs to be actively incorporated into planning decision making.

Empowering the next generation of Landcarers

- There are over 900 Landcare/Bushcare groups in urban Sydney.

- Most people in mainstream Landcare are over 50; there is a missing demographic in the 18’s to early 30’s age group.

- Intrepid Landcare leadership retreats are a key way of connecting with young people and getting them involved.

- A national network of new Intrepid Landcare groups now exists across different parts of Australia.

Urban Apex predator – Powerful Owl in Great Melbourne Region

- The Powerful Owl is Australia’s largest owl species, standing at about 65 cm tall.

- To survive in urban areas, the Powerful Owl needs; a prey source of possums, roosting sites and large nesting hollows.

- A pair of owls in urban environments on average need 638 ha / 6.38 km2 of space or 360 MCGs.

- Natural nest hollows are up to 2 meters deep and half a meter round and can take several hundred years to form.

Linking landscapes & community through wildlife gardening

- Cities can improve their social and ecological wellbeing through new human nature relationships and understandings.

- Your garden can be part of a landscape where indigenous plants and animals live.

- Gardens for Wildlife Victoria has a vision for biodiversity conservation to be understood and embedded in the lives of all Victorians, particularly urban residents, who make up the majority.

List of speakers and topics

Embedding ecology and biodiversity in urban parks - linking science with action -Dr Amy Hahs, Senior Lecturer In Urban Horticulture Ecosystem And Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne

Empowering the next generation of Landcarers - Elisha Duxbury, Local Landcare Coordinator, Greater Sydney Landcare Network

Urban Apex predator – Powerful Owl in Great Melbourne Region - Nick Bradsworth, PhD Candidate in urban ecology, Deakin University

Linking landscapes and community through wildlife gardening- Dr Laura Mumaw, Gardens for Wildlife – Program Facilitator, RMIT

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Embedding ecology and biodiversity in urban parks - linking science with action

Dr Amy Hahs, Senior Lecturer In Urban Horticulture Ecosystem And Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne

Amy acknowledged traditional owners of the Wadawurrung People of the Kulin Nation.

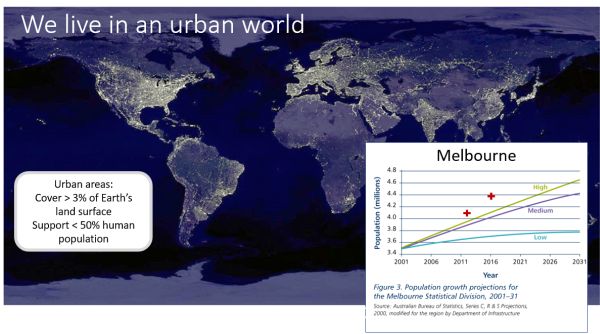

Living in an urban world

Amy introduced her presentation by providing an overview of urbanisation across the globe, covering more than 3% of the Earth’s land surface and supporting at least 50% of the human population the urban landscape has a significant ecological footprint.

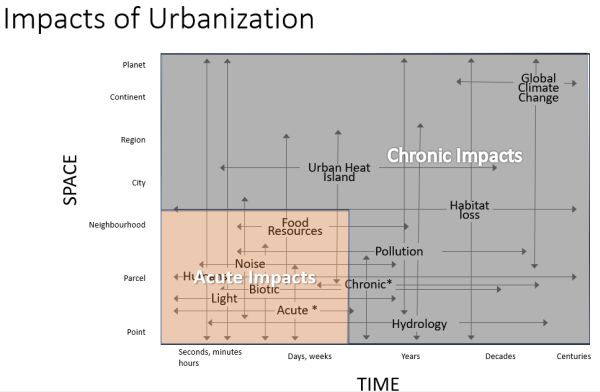

Impacts of urbanization

Amy discussed a broad range of impacts which she grouped into Acute impacts and Chronic impacts. Impacts can also be measured in Space (local scale to planet scale) and Time (from seconds to centuries).

Biodiversity responses to impacts of urban landscapes

Amy spoke about three main pathways organisms can respond to the urban environment. The urban pool starts out with an initial group of species and some additional invasive species. Three main pathways;

Able to join the new urban species pool – species pre-adapted to urban conditions

Likely to be lost from the urban environment – species maladapted to urban conditions, lost due to migration or local extinction; these are typically species with a complex life history.

Adaptive response – species which are able to adapt through natural selection response

Amy spoke about the need to soften the way we approach urban landscape development so more species are going to be pre-adapted to urban conditions, leading to a greater number of species joining the urban species pool and a reduction in the number of species lost through local extinctions.

Cities are Hotspots for Biodiversity

Urban landscapes are often located in highly productive landscapes with naturally high levels of indigenous biodiversity. 30% of Australia’s threatened species occur in cities (Ives et al. 2016). https://lifeontheverge.net/2017/09/19/which-threatened-species-share-your-neighbourhood

Cities may contain the only remaining examples of past landscapes.

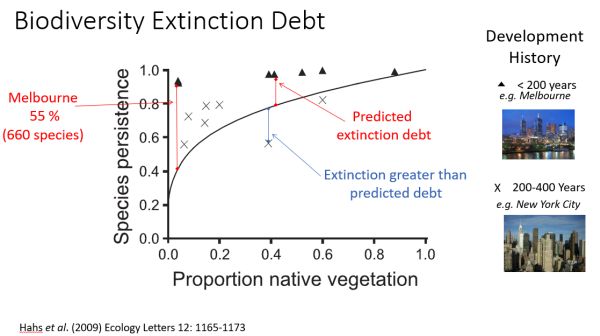

Biodiversity extinction debt

Amy spoke about the concept of extinction debt which relates to the amount of native vegetation within the city and the length of time a city has been undergoing urbanisation.

In Melbourne, only about 4% of native vegetation is remaining which equates to 55% of the plant species or 660 species that could disappear over the next 100-150 years if action is not taken.

Creating spaces that support people and nature

Amy spoke about some of the projects which she has been involved in.

Urban Ecology Park Scenario

Working with local government to develop designs for an urban urban ecology park scenario, with the opportunity to cater for both people and nature, and develop an entirely new park experience. The project required collaboration between landscape architecture, with the focus on design, and urban ecology, with the focus on providing habitat for biodiversity, and opportunities to engage people with the natural environment. The outcome was a concept plan that combined elements of both the recreational park and the conservation reserve, to become a new type of hybrid park that supported people and nature.

Urban Ecology Park Scenario for Moonee Valley City Council ‐ ZM Environments and ARCUE. Metherell, Hahs & McDonnell (2013) Full report pdf

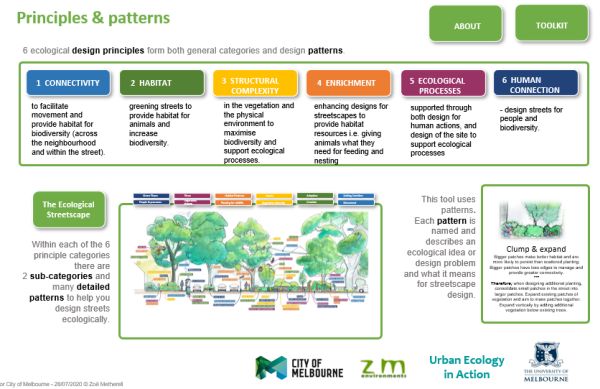

Ecological Streetscapes

Incorporating ecology and landscape architecture. Streetcapes are a heavily contested space, Amy spoke about applying biodiversity knowledge developed from research within the constrains and limitations urban landscapes.

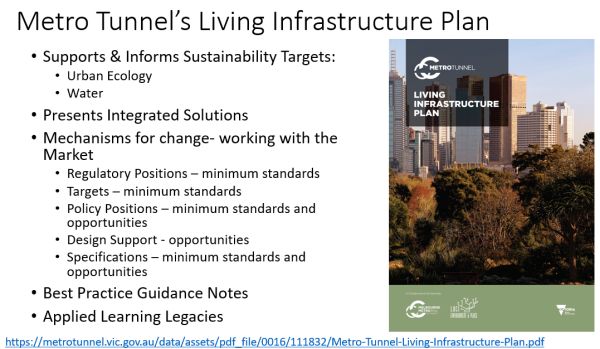

Metro Tunnel’s Living Infrastructure Plan

Amy spoke about incorporating biodiversity into day to-day activities, she used the example of the Metro Tunnel’s Living Infrastructure Plan which has involved developing a stronger urban ecology component in the project. Amy has been working on the project developing stronger sustainability targets in relation to urban ecology and water, project Alignment & Components and the Environmental Effects Statement.

Metro Tunnel design strategies and plans https://metrotunnel.vic.gov.au/planning/design-strategies-and-plans

Metro Tunnel Living Infrastructure Plan pdf https://metrotunnel.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/111832/Metro-Tunnel-Living-Infrastructure-Plan.pdf

Involvement and collaboration

Amy spoke about the need to involve people from a range of disciplines in the process of changing the way planning is approached in urban environments. Ecology needs to be actively incorporated into decision making. Collaboration and evaluation need to extend beyond individual projects and include;

- Government- Local, State, National

- Planners

- Landscape Architects

- Developers

- Builders

- Architects

- Horticulturalists

- Traditional Owners

- Scientists

- Land-managers

- Artists

- Community

Amy acknowledged the interdisciplinary involvement of people contributing to the project.

Key points from questions

- Incorporating vegetation into urban design needs to overcome safety concerns regarding visibility and the cost of establishing and maintaining vegetation. There are also a lot of unknowns for developers which can be addressed through environmental design. A 30% volume of shrubs can yield a significant environmental gain.

- Environmental design is an important consideration regarding Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) ratings.

- The Surf Coast Shire has produced helpful instructions on how to landscape a garden with bushfire in mind. View pdf

- Research focused on urban park design (which Amy has been involved with) found clumped plantings of trees where the tree canopies were connected with a gap between clumps is better for reducing impacts from fire rather than scattered tree cover. The connection of understory vegetation to the canopy also increases fire behavior.

- Some peri urban fringes of Melbourne may have some characteristics with rural towns but it is important to consider the specific site circumstances when undertaking planning to achieve the best ecological outcomes.

- It has been pleasing to see the Metro Tunnel’s Living Infrastructure Plan being implemented at the Parkville construction site in terms of incorporating design specifications and habitat plantings.

- Ecological monitoring needs to be considered when changing the vegetation composition and structure during projects. Birds such as the Noisy Minor are more likely to dominate where there is tree canopy with lawn type ground layer rather than shrubs. Designs can incorporate more shrub cover to provide more habitat for insects and small birds. Ecological processes take time so measuring the success of a project takes time as well. Being realistic about what success looks like is very important.

- Urban parks need to reflect the diversity of needs and experiences of people. Urban park design is not one size fits all.

Empowering the next generation of Landcarers

Elisha Duxbury, Local Landcare Coordinator, Greater Sydney Landcare Network

Elisha paid respect to the traditional owners of the lands in which she works.

Elisha is focused on exploring ways of empowering the next generation of Landcarer’s to care for Sydney’s threatened bushlands through local Intrepid Landcare groups who provide training and volunteering opportunities through the Get Your Hands Dirty program.

Mainstream Landcare to Landcare in Cities

Elisha spoke about the benefits of mainstream Landcare to farmers and landscapes in rural areas and the need to adapt the way Landcare is applied to the Cities.

Landcare in the City

There is a wide variation in the way Landcare is delivered in Sydney. There are over 900 Landcare/Bushcare groups in urban Sydney. In the urban fringe areas, it is more mainstream Landcare, the program also supports the Bushcare community who focus on Public land. Other programs include Citizen Science, Coastcare, Remote Landcare in National Parks and Indigenous Landcare.

Where are the young people?

Elisha spoke about the fact that most people in mainstream Landcare are over 50 and there is a missing demographic in the 18’s to early 30’s age group. There is a need to recruit young people into the networks which is now being achieved through Intrepid Landcare.

Intrepid Landcare began from only a few community leaders who could see an opportunity to attract young people into action by organising a retreat which worked so well that a national network has now been set up to form a number of new Intrepid Landcare groups across different parts of Australia.

Establishing Intrepid Landcare in Sydney

Sydney Landcare Network ran four Intrepid Landcare leadership retreats each with about 20 participants. The retreats provided an opportunity for young people to learn about what is involved in Landcare and introduction to country from an indigenous perspective. The retreats involved planning sessions for participants to decide what they would like to see in their local area. The retreats are also about having fun, connection and ensuring being at the retreat is a good experience.

There are now Intrepid Landcare tribes at Central Coast Intrepid and Western Sydney. The tribes have planned initiatives relevant to their areas and involve young people in doing on-ground work to help the environment.

Get Your Hands Dirty

The Get Your Hands Dirty project was initiated after the retreats in response to young people wanting to have an opportunity to connect with more young people and get them involved in their groups.

A program of monthly on-ground volunteering projects was set up to connect young people with local Landcare groups. Progress includes;

- A pilot event on 2nd June 2019 at former wildlife research station at Muogamarra Nature Reserve involved 40 young people

- Funding to run monthly events over 2020-2021

- One event to provide training for young people

- Four events delivered before COVID lockdown

- Over 40 people each in the GYHD Facebook group and subscribing to the newsletter

- More events to come

Key points from questions

- Covid-19 has made on-ground activities more difficult but there could be opportunities for smaller groups with correct hygiene measures in place to carry out projects depending on the lock down level.

- Intrepid held their annual event on-line this year.

- It can be more challenging to keep up the engagement level with some young people due to their own time constraints but it still very important to keep them involved as they may contribute when they have more time.

- Social media plays an important role in engaging with younger people.

- Landcare in Sydney reflects the diversity of the population.

- Funding for the Get Your Hands Dirty has been possible though NSW State Government local grants programs and a Federal Coast Grant.

Urban Apex predator – Powerful Owl in Great Melbourne Region

Nick Bradsworth, PhD Candidate in urban ecology, Deakin University

Nick’s research is focused on addressing a major knowledge gap in understanding the movement, pathways and core habitat available to an urban apex predator, the Powerful Owl. At present Nick is, 1.5 years into 3-year PhD but has been involved with urban Powerful Owl research for over 25 years.

Nick acknowledged the traditional owners of the land where he presented his talk and where he has been carrying out his research, the Wurundjeri people and the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation.

Research context

Nick spoke about global ecological issues and two distinct things that are having an impact on biodiversity;

- Decline in apex predators (apex predators are necessary to suppress more abundant trophic levels)

- Urbanisation (habitat loss, fragmentation, impervious surfaces, loss of food resources for apex predators)

Some apex predators live in urban environments, for example; Coyotes, Leopards, Cooper’s Hawk, Peregrine Falcon and Cougars. Many apex predators are very difficult to study with cryptic, often nocturnal behaviour with large spatial requirements and because of this, are found in low abundance.

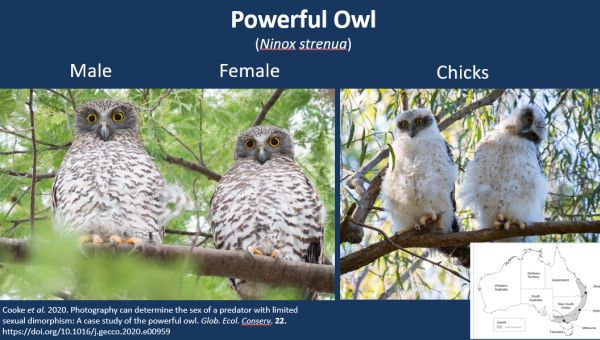

The Powerful Owl

The Powerful Owl is Australia’s largest owl species, standing at about 65 cm tall. They are found down the east coast of Australia.

It is difficult to distinguish between males and females, the face mask is used as the main identifying feature. Males also have a larger body size than females weighing about 2 kg, females weigh about 1.2 kg. Chicks are very fluffy and white with dark masks; they emerge from the hollows around September – October.

Further reading: Cooke et al. 2020. Photography can determine the sex of a predator with limited sexual dimorphism: A case study of the powerful owl. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22.

Key factors to survive in urban areas

- Prey source (a Powerful Owl can consume 250- 300 possums in one year)

- Roosting sites – structurally diverse

- Large nesting hollow - required for winter breeding, not all year around

Threats within the urban environment

- Death from road traffic – tends to be an increasing problem as more roads are being built/upgraded associated with housing estates

- Predation - fledging owls which may not have fully developed flight can end up on the ground where they can be taken by cats and foxes

- Lack of hollows – impacts on habitat for breeding owls

Current research

Nick spoke about his research aimed at answering some of the questions regarding spatial requirements which began in 2016;

- How much habitat do they need?

- How much habitat is available?

- How do they use the available habitat?

Results from tracking

- GPS tracking data recovered for 20 individuals (the GPS transmitters record a GPS position every 20 min throughout the night)

- Over 20,000 GPS positions collected (between 1-3 months of time-sequenced movement tracks per owl)

Three types of movement / behaviour have been determined form the tracking data;

- Prey handling – short movement length

- Foraging – medium movement length

- Transitory movements – long movement length

Nick referred to the following publication if people want for more details. Carter et al. (2019). Joining the dots: How does an apex predator move through an urbanizing landscape? Global Ecology and Conservation 16, 1-12.

41 nights of activity is condensed into 30 seconds.

Red = prey handling, Blue = foraging, Yellow = transitory movements (Green areas = riparian vegetation which is very important for movement)

Powerful Owls were more likely to make long transitory movements towards the end of the night where they have to pass over infrastructure and paddocks to connect to the next habitat patch, also Powerful Owls avoid high density residential areas and prefer treed areas lining paddocks.

Source: Joining the dots: How does an apex predator move through an urbanizing landscape? ; Nicholas Carter, Raylene Cooke, John G.White, Desley A.Whisson, Bronwyn Isaac, NickBradsworth

Home range

A pair of owls in urban environments on average need 638 ha /

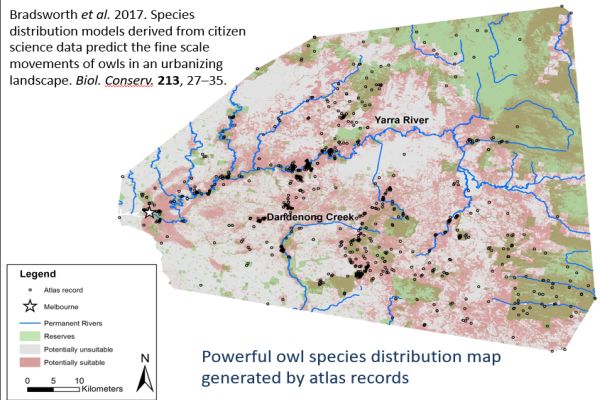

Determining available habitat in Melbourne

Nick spoke about work undertaken as part of his Honors research in 2017. A species distribution model was developed using Citizen Science data. The model is used to predict which areas might be suitable for Powerful Owls and which areas are not suitable. Nick encourages anyone who sees or hears a Powerful Owl to report it via Birdlife Australia – Birdata.

The black dots indicate Powerful Owl records. Grey areas = potentially unsuitable; Pink = potentially suitable; Green = reserves

Bradsworth et al. 2017. Species distribution models derived from citizen science data predict the fine scale movements of owls in an urbanizing landscape. Biol. Conserv. 213, 27–35

Roosting

Owls show a high degree of flexibility in the trees in which they roost. Some owls only roosted in one or two tree species whilst others roosted in up to 9 tree species. Non-indigenous trees (pines, oaks, willows) can form part of the roosting habitat, provided they have a dense canopy but many non-indigenous trees drop their leaves in winter which means owls need to shift to indigenous trees with dense cover.

Roosting sites are evenly split between the mid-storey and canopy vegetation.

Clues for locating a roost site

Nick spoke about the way he goes about refining the search for roost sites. Starting with some of their favourite tree species he looks for trees with a dense canopy, signs of whitewash, feathers and pellets of undigested material coughed up.

How you can help

Nick spoke about the need to be careful when sharing information about Powerful Owls. They are a threatened species and information needs to be shared with caution to avoid having the birds harassed. Powerful Owls are particularly sensitive to disturbance during the breeding season. Submit data to https://birdata.birdlife.org.au/

Other ways in which people can help the Powerful Owl are;

- Help to control spread of environmental weeds

- Plant indigenous plants for roosting

- Maintain large old eucalypts in your backyard

Key points from questions

- Artificial nest boxes have had limited success but some new research is being conducted by University of Melbourne which is comparing various types of artificial nest boxes.

- A lot of thought needs to go into working out if the habitat is suitable and if there is a potential pair of owls that might use the box. It would be best to see the results of the artificial nest box research before proceeding.

- It is thought the offspring remain on the periphery of the parent owls home range for a number of years before they move away.

- There can be a small amount of territory overlap within the home range area of owls.

- Natural nest hollows are up to 2 meters deep and half a meter round. These types of naturally occurring hollows can take several hundred years to form.

- Riparian zones which contain tree cover are useful areas for Powerful Owl habitat.

- There is concern that the 2020 bushfires have reduced Powerful Owl habitat right across their distribution. In urban environments, urban parks are generally not burnt which may provide some degree of protection.

Contact:

Linking landscapes and community through wildlife gardening

Dr Laura Mumaw, Gardens for Wildlife – Program Facilitator, RMIT

Laura is a researcher at RMIT University Centre for Urban Research and is also on the Gardens for Wildlife Steering Group Committee. Laura’s research is focused on biodiversity stewardship and how cities can improve their social and ecological wellbeing through new human nature relationships and understandings.

Laura acknowledged the traditional owners of the lands covered by the seminar and the Kulin Nation from where she presented.

Urban nature

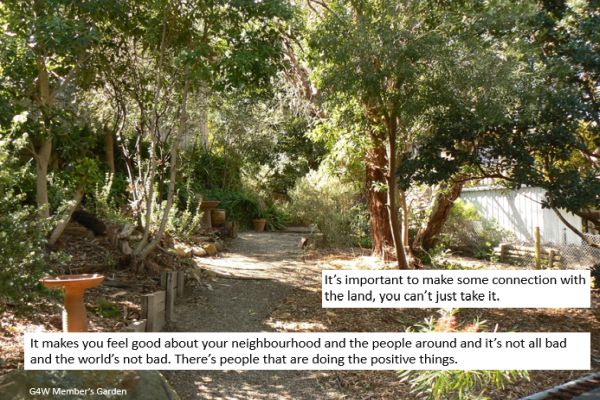

Laura spoke about how urban areas change the ecosystems in and around them. Habitats are fragmented and left as patches but for plants and animal communities to thrive habitats need to be large enough and connected. Gardens can play a role in the urban matrix to support indigenous plants and animals.

Laura discussed 5 basic needs for plants and animals to survive across the landscape;

- Nutrients

- Water

- Shelter

- Reproduction

- Social Needs

Fostering locally native species

Studies have shown that locally native species can be fostered in urban neighbourhoods, particularly if we take a landscape and community focus, combining public land management and wildlife gardening. It should be noted that private land can be a major contributor to biodiversity in urban areas as it is usually the greatest proportion of land in urban areas.

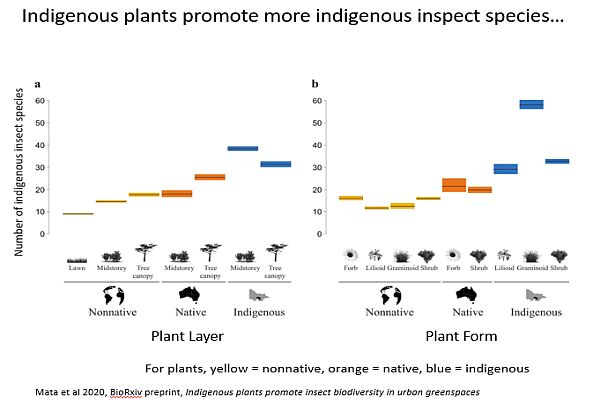

Laura spoke about a study which demonstrated the importance of indigenous vegetation to indigenous insects. Mata et al. 2020, BioRxiv preprint, Indigenous plants promote insect biodiversity in urban greenspaces

Wildlife gardening stewardship

Laura spoke about wildlife gardening as having a purpose to nurture the ability of a place to support indigenous flora and fauna for future generations of people and wildlife.

Laura’s research has focused on the social dimensions of how we can expand wildlife gardening stewardship in ways that link landscapes and build human-nature relationships. She is looking at how to involve and keep residents in wildlife gardening as a community effort. Laura research is also wanting to determine;

- What are the wellbeing impacts for individuals and their communities and how can we strengthen them?

- How can we spread local action and link it with government policy and priorities?

Papers from Laura’s research;

Knox City Gardens for Wildlife – case study

Laura spoke about linking the Knox City Gardens for Wildlife (G4W) as part of her PhD. The G4W program began in 2005 as a partnership between Knox City Council and a community group, Knox Environment Society (KES ) which runs an indigenous plant nursery. Any resident can join, receives a garden visit, report, and then newsletters and event invitations. At present there are more than 1000 households and growing. Members gardens support the City of Knox indigenous biodiversity.

Key features which engage and sustain residents in wildlife gardening;

- Face-to-face garden visit

- Indigenous plant nursery plant vouchers

- Endorsement of garden’s contribution

- Learning by doing

- Community involvement

- Communication hubs – nursery and council office

A survey showed that 96% of members reported planting indigenous species and 88% removing environmental weeds.

Important messaging at every step: Your garden is part of a landscape where indigenous plants and animals live. Through our gardening, with council and community, we can support indigenous plants and animals to survive.

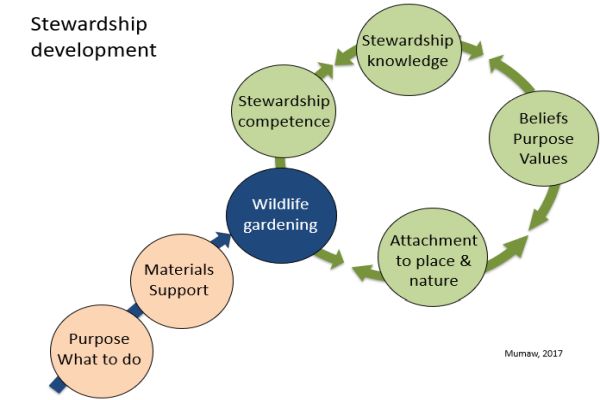

Stewardship development

As part of her research Laura posted a model for how urban land stewardship develops.

It starts with an introduction phase where you are shown what you can do and how (in the Knox case, a garden and nursery visit), and, once you begin (blue circle), a development phase, driven by learning by doing (the green arrows). Stewardship develops through an interplay between the gardening, gaining competence and confidence, increasing stewardship knowledge, strengthening stewardship beliefs and purpose, and growing attachments to place, nature and community.

Rewards from Wildlife Gardening

Laura highlighted may of the benefits obtained from Wildlife Gardening;

- Mental restoration, happiness, pleasure - wellbeing aspects common to many nature experiences

- Expressing oneself, being creative, discovering new things

- Special wellbeing benefits linked to making a contribution, living a meaningful life

- Knowing you are doing it with council and other community members builds social and landscape connections

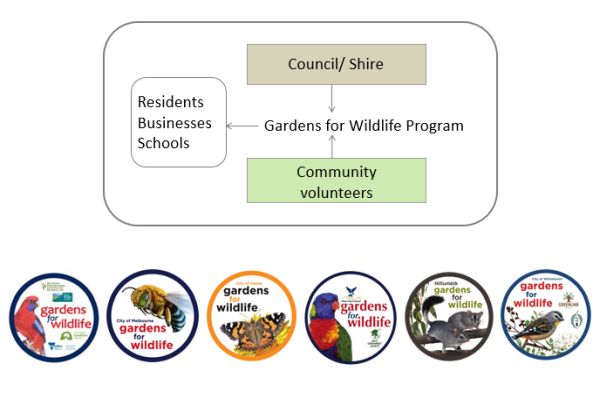

Gardens for Wildlife Victoria

Gardens for Wildlife Victoria began in 2016 as an initiative from a broad study of how to better involve the community in natural resource management.

Its vision is for biodiversity conservation to be understood and embedded in the lives of all Victorians, particularly urban residents, who make up the majority.

Laura spoke about the stewardship framework and the approach taken to implement the program. Key features;

- Gather champions from community and local or regional government to codevelop and implement wildlife gardening programs in their areas.

- Use Knox gardens for wildlife as a model to adapt locally

- Link, mentor, and support program leaders

- Monitor, evaluate, and learn from doing

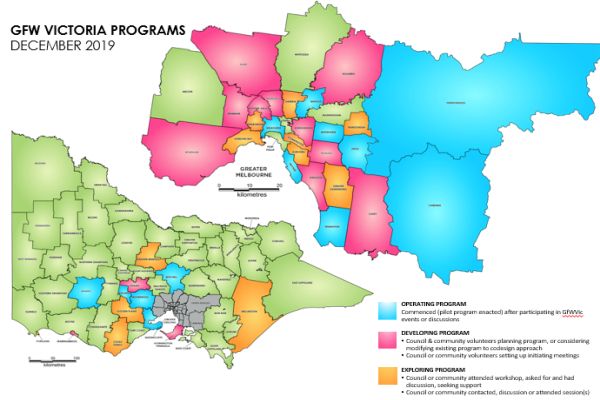

Since August 2016, the number of local government areas developing or running wildlife gardening programs by participants in the network grew from 1 in Knox to 39 of the 79 LGAs Victoria. Most of the programs being within Melbourne and rural cities.

Expanding stewardship

Laura spoke about six interlinked factors responsible for the up-scaling impacts in Gardens for Wildlife Victoria;

- Empowerment – local program leaders

- Local co-design and development

- Endorsing an approach that conservation is doable and valuable in urban areas

- Messaging - linking the landscape and community

- Resources – time and capacity building

- Networking – inspiring champions, building capacity and supporting innovation

Key points from questions

- CFA guidelines are adopted as part of Gardens for Wildlife. Having councils involved helps ensure Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) ratings are taken into account.

- There does not appear to be a major advantage in either the community or council starting a program. Each of the ways of starting have their own challenges and often comes down to individuals who understand what it takes to build relationships and have links within their communities.

- Community leader burnout is a challenge which can be overcome if 3 or 4 other people are sharing the load.

- Some councils have incorporated wildlife gardening into environmental education for schools’ programs. Further opportunities are being explored to include schools in the community and council wildlife gardening partnership.

- The community groups include, environment advisory groups, environment society groups, individual community members and in rural areas, Landcare Groups.

- Human - wildlife conflict has not been an issue but the issue of mature trees impacting on neighbours can cause tension. Being part of a broader program is a way of overcoming issues as there is more advice and backup to draw on.

- Engaging local residents to add tree canopy to their gardens is not so much of an issue as getting people with mature trees or large trees midway in their growth to understand the value of the trees and retain them.

- Gardens for Wildlife is not limited by the size of the property. Anyone with space can participate and contribute towards creating a better environment.

More information:

Knox City Gardens for Wildlife (G4W)

See also:

Biodiversity conservation in urban and fringing landscapes - 31 October 2012 pdf