SWIFFT Seminar notes 20 May 2021

Crossings for wildlife

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 159 participants via Microsoft Teams and streamed live via YouTube. SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Thanks to Michelle Butler who chaired the session from Ballarat and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

Key points summary

Wildlife crossings across the world

- Each and every road comes with an environmental impact on wildlife through noise, traffic and habitat fragmentation.

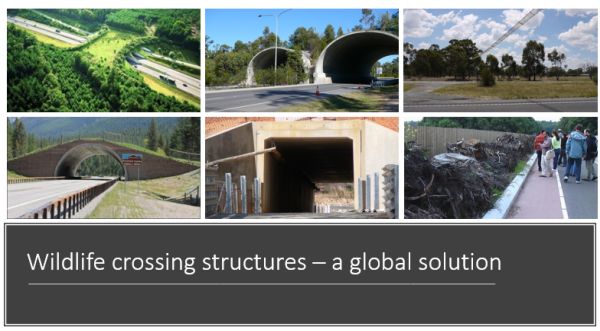

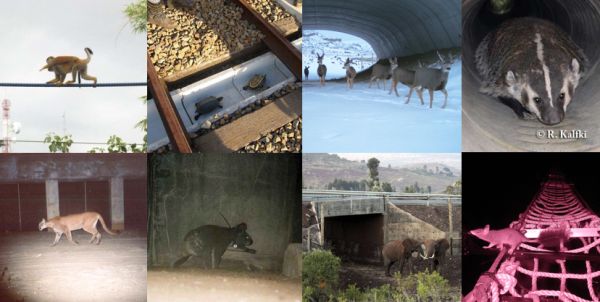

- Crossing structures include; overpasses, underpasses, land bridges, vegetated overpasses, rope bridges and modifications to existing concrete structures using branches, poles and rocks.

- Wildlife crossings are not just about promoting movement of wildlife across roads but are part of an effort to reduce roadkill.

- Wildlife crossing projects should measure the effectiveness in promoting movement and connectivity and mitigating the barrier effect.

- Wildlife crossing structures can be effective in protecting wildlife – wildlife is important, roadkill is bad.

- Design of crossing structures including enhancements to existing structures needs to include habitat enhancement and monitoring.

- VicRoads undertakes monitoring of wildlife crossing structures and conducts research to improve their effectiveness.

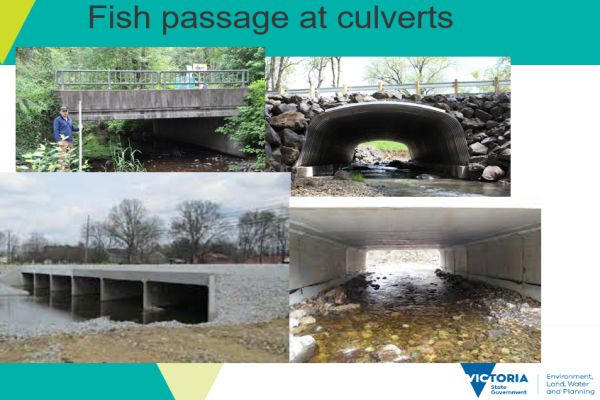

- Fish move long distances for migration and spawning.

- Barriers in streams can be detrimental to entire fish populations.

- Most Fishways contain a series of pools which allows the fish to move against the current past the barrier.

- Monitoring of new fishways at Dights Falls on the Yarra River detected over 40,000 fish comprising 17 species (12 native sp.). Over 1,000 fish per hour used the fishways in the peak migration.

Virtual fencing on Phillip Island

- The virtual fencing project is being undertaken at Phillip Island in partnership between Victoria University, Phillip Island Nature Parks and Bass Coast Shire with support from Citizen Science.

- Virtual Fencing is an active electronic protection system that alerts animals before crossing the road when a vehicle is approaching between dusk to dawn.

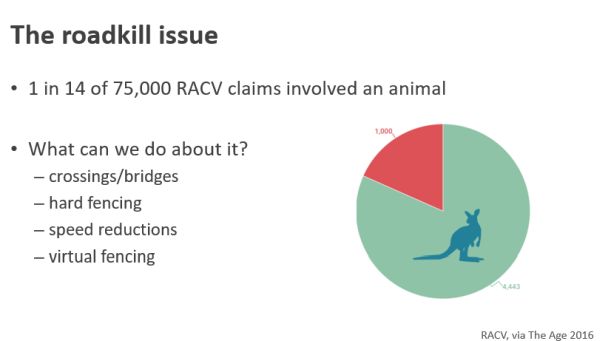

- In 2016, the RACV recorded about 4,500 collisions with animals (8 out of 10 collisions) were with macropods (kangaroos, wallabies).

- The level of roadkill on Phillip Island has increased from 1.95 roadkill/km/month in the 1990’s to 2.39 roadkill/km/month in 2014.

List of speakers and topics

- Wildlife crossings across the world – how well do they work? - Kylie Soanes, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences - The University of Melbourne

- Roads and Wildlife Structures - Tahlia Townsend, Environmental Graduate with the Department of Transport - Regional Roads Victoria

- Fish Passages - Justin O'Connor, Senior Scientist, Fish Assessment - Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

- Virtual Fencing on Philip Island -Christine Connelly, Lecturer in Environmental Science (College of Engineering and Science) - Victoria University

Speaker summaries

Wildlife crossings across the world – how well do they work?

Kylie Soanes, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences - The University of Melbourne

Some of the information in Kylie’s presentation has not yet been published and is therefore omitted in part from this summary.

Kylie’s presentation provided a global overview of measures undertaken to mitigate the barrier impacts of roads. Kylie has collaborated with road ecologists from around the world to evaluate the current state of literature relating to wildlife crossing structures.

Kylie gave a simplified view of road ecology which involves taking a wildlife population and allowing a limited number of animals to move from one side of the road to the other for mating, feeding etc. If too many lives are lost whilst crossing the road or deterred from crossing then the population suffers and can become extinct.

Wildlife crossing structures

Kylie spoke about some examples of wildlife crossing structures which have been used in different parts of the world e.g., overpasses, underpasses, land bridges, vegetated overpasses and rope bridges. Crossing structures also include modifications to existing concrete structures to incorporate wildlife movement by using branches, poles and rocks.

How effective are wildlife crossing structures at promoting wildlife movement across roads?

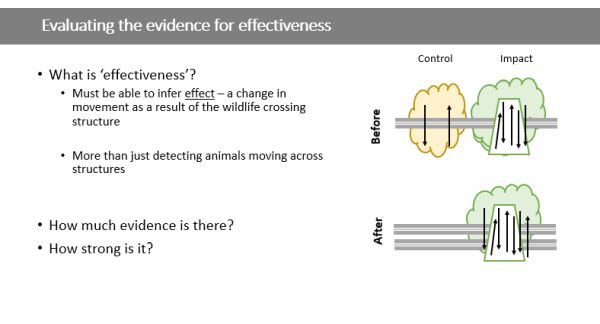

Kylie discussed the need to evaluate the effectiveness of crossing structures. There are many studies showing wildlife using crossing structures but there is an increasing need for science to focus on measuring the effectiveness in promoting movement and connectivity and mitigating the barrier effect.

Kylie worked with a number of road ecologists from around the world to evaluate the current state of literature relating to wildlife crossing structures. The team determined that for a piece of research to provide evidence on effectiveness it must be able to infer an effect, i.e., a change in movement across the road due to the wildlife crossing structure. There must be a comparison, either between mitigated sites and no structure sites or measuring animal movements before and after structures are installed.

The team conducted an enormous review of literature (1,323 papers) on anything that measured terrestrial wildlife using a crossing structure to move across a road and identified 240 studies which detailed unique investigations but only 42 studies had information on the effectiveness of the wildlife crossing structure. The team also evaluated the evidence used in the 42 studies to rank them High, Medium and Low evidence.

Kylie spoke about species that were most evaluated i.e., mammals that are easily monitored or which have high impact cost to humans. She pointed out that lesser studied taxa such as amphibians and reptiles are particularly vulnerable to roads but not studied to the same extent as mammals.

Preventing mortality

Wildlife crossings are not just about promoting movement of wildlife across roads but are part of an effort to reduce roadkill. Research conducted by Rytwinski et al 2016, found that fencing is a critical component of reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions. Crossing structures without fencing generally don’t reduce roadkill.

Evaluating effectiveness

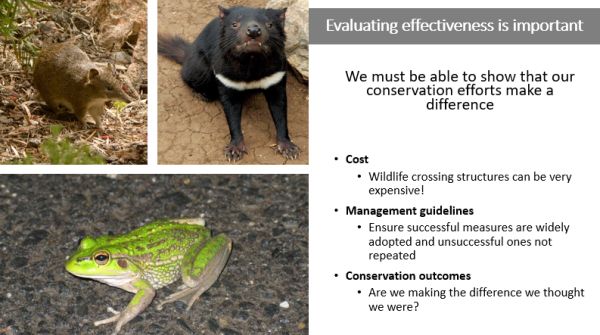

Kylie explained that we must be able to show that our conservation efforts make a difference. Considering the costs involved with wildlife crossing structures it is important to be able to measure effectiveness.

Evaluating effectiveness helps in the development of management guidelines for road agencies and land managers to ensure successful methods are adopted and unsuccessful ones are not repeated.

Kylie pointed out that one-off case studies involving a species at a particular location is not enough to measure effectiveness. What is needed is a greater number of more robust evaluations of effectiveness. Robust evaluation needs:

- Comparison to unmitigated state (control site or before/after data)

- Replication (in space at multiple sites, time in years or preferably both)

- Control for confounding factors (to ensure conditions are comparable across mitigation sites)

- Duration (longer term studies)

- Link mechanism to population-level effects

Kylie acknowledged the co-authors and people she has been working with on this research.

Contacts:

Kylie's research web blog https://lifeontheverge.net/

About Kylies research https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/profile/176188-kylie-soanes

Key points form questions

- Echidnas have been observed using under road culverts.

- Where new roads or road upgrades incorporate crossing structures, it is important to include non-mitigated sites as part of the evaluation. This enables comparisons to be made between mitigated and non-mitigated sites.

- For road overpasses across streams, it is beneficial to incorporate more stream bank either side of the creek which allows wildlife to move along the bank of the stream under the road.

- Wombats use culverts and tunnels.

- Some species of bats benefit from road overpasses because they do not move about in open areas and are restricted to tree lines. Other species of bats are not restricted by open areas. Therefore, it is important to know which species crossings are intended for, particularly when evaluating effectiveness.

- Multiple crossing structures within home ranges can assist in reducing territoriality which may restrict the use of the crossing structure.

- There is no definitive evidence that crossing structures increase predation.

- We need to form partnerships with road agencies to improve the evaluation of crossing structures which in turn can assist with more efficient and cost-effective design.

- Citizen Science can play a role in collecting road kill data.

- Roadkill reporter app

- iNaturalist Roadkill project

- Current roadkill information is unable to provide answers on the level of roadkill in the past, where it could have been so high that populations have become locally extinct.

- Other structures impacting on wildlife movement include, rail lines, aqueducts, powerlines. Roadside wire barriers and concrete road dividers can also trap wildlife which means escape openings should be provided.

- More information from Kylie on Glider Poles

Roads and Wildlife Structures

Tahlia Townsend, Environmental Graduate with the Department of Transport - Regional Roads Victoria

Tahlia spoke about work she undertook doing a review of wildlife structures on roads as part of her internship with the Department of Transport.

Virtual fences

These are devices which detect a car and emit a sound/light to deter animals from the roadside. Tahlia pointed out that virtual fences are new technology but relatively inexpensive compared with structures. Being new technology there is little scientific evidence for measuring their effectiveness and more research is required. One advantage with virtual fences is that they allow unrestricted movement across a road when no vehicles are present. Problems such as habituation (animals becoming familiar with the warning signal), unintended effects on wildlife and distractions to drivers needs further research before implementation on Victorian roadsides.

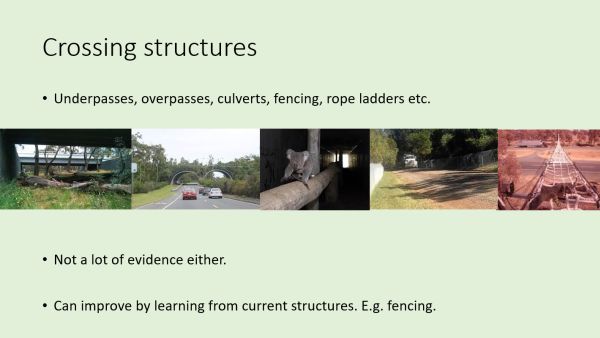

Crossing structures

Tahlia spoke about a range of crossing structures; underpasses, overpasses, culverts, fencing, rope ladders etc. and her work in analysing the effectiveness of crossing structures in Victoria.

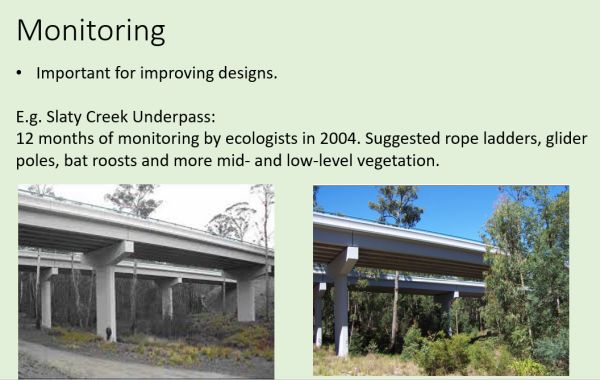

Monitoring

Tahlia spoke about an example of monitoring Growling Grass Frog crossings at the Craigieburn bypass. The project involved 12 months of monitoring by ecologists which found only 2 of 10 culverts were appropriate. Recommended improvements included; improving vegetation and water retention, and removing rocks. This type of monitoring helps to refine the design of crossing structures for Growling Grass Frogs to make them more successful.

Monitoring existing structures to improve their functionality for wildlife is also important. Tahlia spoke about the Slaty Creek Underpass which had 12 months of monitoring by ecologists in 2004. Recommendations included; rope ladders, glider poles, bat roosts and more mid- and low-level vegetation to improve wildlife movement.

Tahlia has recommended that monitoring and maintenance be included in the budget and protocols for installing wildlife crossing structures by the Department of Transport. It is also necessary to keep an eye out for other research/monitoring projects involving wildlife crossing structures and work collaboratively where possible.

Timing

Tahlia highlighted the importance of allowing enough time for monitoring to accurately determine the use of a crossing structure by wildlife as it may take some time for animals to habituate to the structure. E.g., rope ladders were assumed ineffective after 6 months of camera trapping but after 6 months possums and gliders started using the ropes.

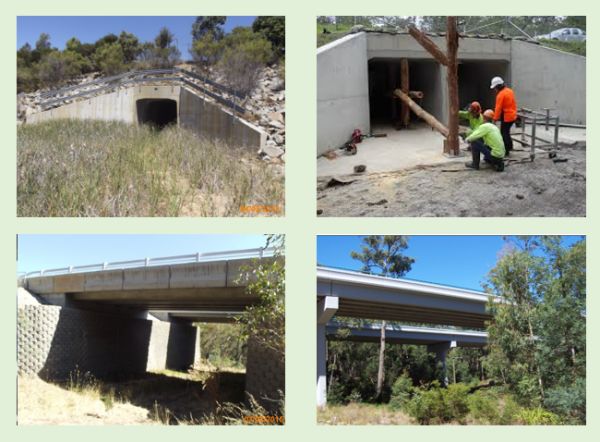

Vegetation

Vegetation can play an important part of crossing structure design. There is a need to consider the difference between simply building a crossing structures which provide the ability for animals to cross compared with encouraging wildlife to use the structure. Low, mid and high- level vegetation is important for success with a diversity of species. If the focus is on a particular species, then vegetation specific for the species is necessary. E.g., trees and logs for koalas.

Adding vegetation to underpasses provides shelter and security for wildlife to move through the structure. Koala poles used in underpasses increase the likelihood of use. Addition of mid storey vegetation and glider poles was found to be effective in allowing wildlife to use the freeway underpass.

Upgrading existing crossing structures by incorporating vegetation is worth looking at as it is no use having a structure that isn’t working.

Connectivity

Tahlia emphasised the importance of looking beyond the immediate crossing structure to take account of surrounding habitat and where animals may be moving. Where possible, crossing structures need to be located so as to connect with habitat either side of the structure. In some instances, the crossing structure could be part of a broader habitat connectivity effort involving habitat/revegetation linkages.

Retrofitting

Retrofitting existing roads needs to be addressed in situations where wildlife is being regularly impacted upon. Retrofitting structures into existing roads can be very expensive but there may be other less expensive measures such as fencing, rope ladders and signage for motorists. Tahlia has recommended that the Fauna Sensitive Road Design Guidelines be expanded to include retrofitting of existing roads.

Fauna Sensitive Road Design Guidelines – VicRoads 2012 pdf

Summary

- Wildlife crossing structures can be effective in protecting wildlife

- Installation is great but improving structures through enhancing habitat and monitoring is essential

- Wildlife is important, roadkill is bad

- Still learning and adjusting to reduce the impacts of roads efficiently and effectively

- We are working on things in the background – e.g., monitoring, research, designing, updating guidelines.

- Communities make a difference, ask for what you want

Key points from questions

- Long-term maintenance needs to be considered. VicRoads undertakes maintenance on their crossing structures.

- More monitoring of crossing structures is recommended. VicRoads are using remote cameras more often as part of the structure installation budget.

- Cameras are great, but they really need to be compared with monitoring movement at control sites/before data, before they can tell you about effectiveness.

- There is very limited evidence to suggest that predation is a major issue which outweighs the benefits gained from installing a crossing structure.

- There is limited evidence that installing rumble strips, sounds etc. will work in deterring macropods from the road.

- Glider poles are used to assist gliding species of mammals but VicRoads tends to use rope ladders.

Fish Passages

Justin O'Connor, Senior Scientist, Fish Assessment - Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

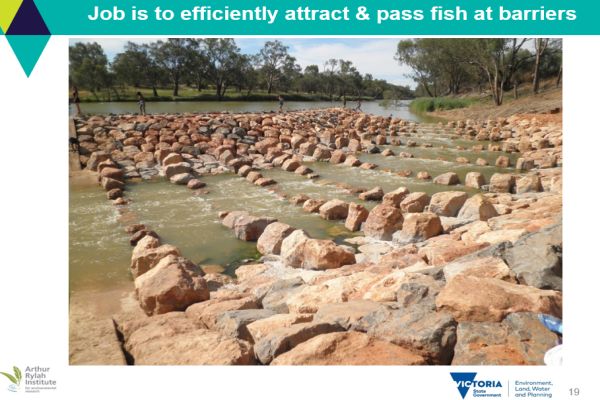

Fish can migrate long distances from tens to hundreds to thousands of kilometres. Depending on the guild of fish, barries to migration can impact on the reproductive cycle. Barriers to fish migration can impact on both upstream and downstream migration.

A large schools of galaxias congregates at a fish barrier, being unable to migrate past the barrier.

Life history strategies of native fish in Victoria

Non migratory species

E.g., River Blackfish which have home range from 500m to 1 km. Barriers can have localised impacts but following catastrophic events barriers can be an impediment to recolonisation.

Migratory species

Diadromous – species which live in freshwater (mostly adult life stage) but must migrate to the sea as part of their life cycle for spawning. Species include; numerous galaxiid species, Australian grayling, Tupong, Australian Bass and Eel species. Even low barriers can impact on the migration. During flooding events fish sometime navigate across barriers which is reflected in the age class of fish during surveys. Some age classes are absent due to barriers and others present due to flooding events. Large barriers can exclude all migration.

Potamodromous – inland Murray-Darling Basin species; Murray cod, Golden Perch, Silver Perch, Hardyhead and Rainbowfish. Spawning migration can occur within the river between upstream and downstream sections of the river system. Barriers interfere with this spawning and the health of the fish populations.

How to improve fish migration

Removal – barrier removal is the number one method but not always feasible.

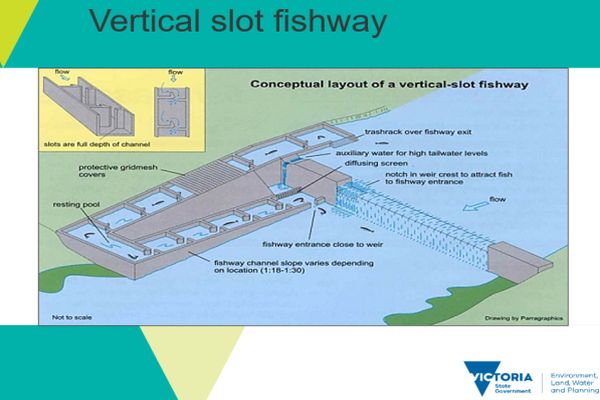

Fishway installation – a fishway is a structure that allows migrating fish to pass over or around an obstacle on a river or stream.

Fishways

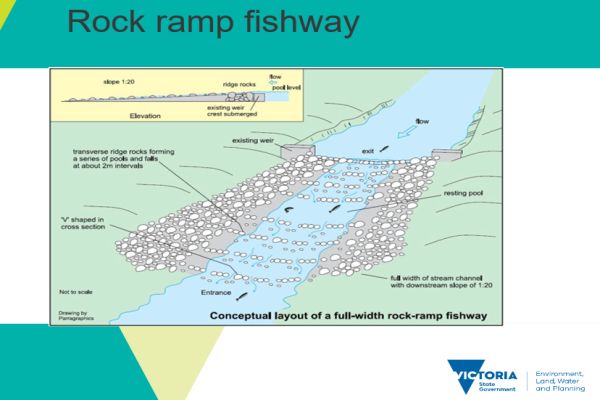

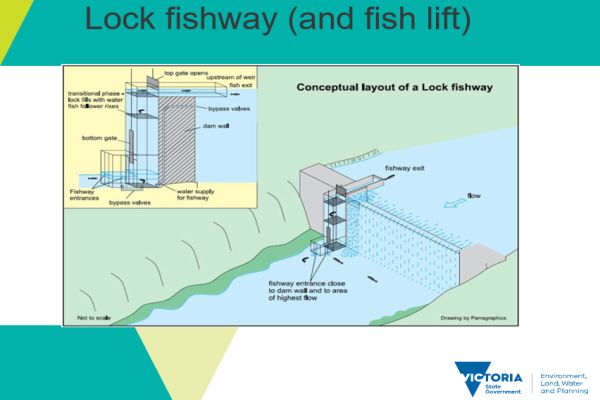

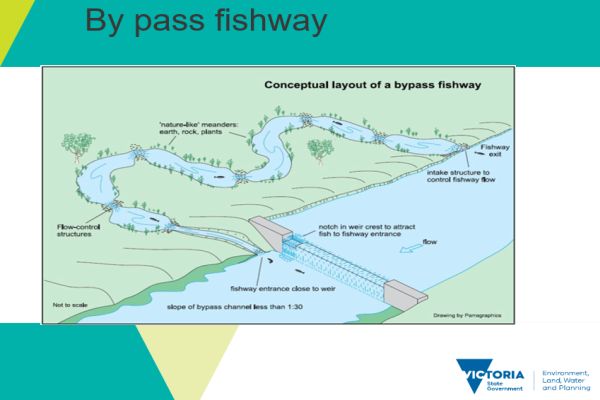

Generally, the fishway contains a series of pools which allows the fish to move against the current and past the barrier. The hydraulics of the flow, velocity and turbulence are designed to suit the swimming ability of the species. Most Australian native species require more conservative hydraulics than northern American fish such as trout and salmon.

History of fishways

The first fishways in Victoria were constructed in the 1980’s. In 1982, a fishway design program was initiated for Australian conditions. Through monitoring, the design of fishways has evolved to suit native species. In 1999, the State Fishway Program was launched with over 60 fishways constructed. In 2002 the Victorian River Health Strategy (VRHS) resulted in re-opening about 7,000 km stream length. A series of design and guidelines documents have been developed through the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy.

Types of fishways

Eel Ramps – designed using artificial grass to allow small migrating elvers to work their way up the ramp above the barrier.

Baffles create pockets of reduced flow and resting areas which allows fish to move against the current.

Justin mentioned a new Australian designed fishway called the Cone Fishway which has been installed on several rivers including the Barwon River. It comes as a flat pack which speeds up installation and is more economical that many other fishways.

Case study: Dights Falls, Yarra River

The Dights Falls weir on the Yarra River near Abbotsford, Melbourne was constructed over 100 years ago and was a major barrier to fish migration. The weir wall was replaced 2010 and a new vertical-slot and rock-ramp fishways were installed.

Monthly monitoring was carried out to demonstrate that the structure worked as designed and provide information to refine the design and act as a basis to improve future designs. Over 40,000 fish comprising 17 species (12 native sp.) were detected using the fishways. When the migration was in its peak the team would detect over 1,000 fish per hour using the fishways.

Justin spoke about a problem the team detected in the vertical slot fishway when the flows exceeded 800 ML/day in that the numbers of migrating fish dramatically dropped off. Engineers were used to model different solutions to reduce the high flow. Modelling detected areas of turbulence which were rectified by installing vertical and horizontal baffles at particular locations within the structure. A new entrance was also modelled and design changes implemented. The modification yielded tremendous results with fish being able to migrate when flows exceeded 800 ML/day.

Key points from questions

- Fishways can make it easier for Carp to move upstream but Justin pointed out that in most streams Carp are already present upstream and downstream of barriers and the benefits of fishways allowing native species to migrate outweighs any issues regarding carp.

- Fishways can take up a lot of space, particularly bypass fishways so any installation needs thorough planning with agencies and landowners.

- Large barriers can impede the downstream movement of fish and is considered in fishway design.

- The cost of fishways depends on the height of the weir and the type of fishway to be constructed. Fishways can range from 100K to over a million dollars. Rock ramp fishways tend to be more economical than vertical slot fishways.

- Maintenance of fishways is important to ensure there are no blockages from debris being washed downstream thus making the fishway ineffectual.

- There are a number different policies and legislation around fishways and obligations of river managers.

- Guidelines for the design approval and construction of fishways in Victoria – ARI Technical Report 274 pdf

Virtual Fencing in Philip Island

Christine Connelly, Lecturer in Environmental Science (College of Engineering and Science) - Victoria University

Christine paid her respects to the traditional custodians of Bunurong land, where her field work is being undertaken.

The virtual fencing project is being undertaken in partnership between Victoria University, Phillip Island Nature Parks and Bass Coast Shire with support from Citizen Scientist, Ron Day. The project is two years into a three-year trial. Christine emphasised that the results so far have not yet been peer reviewed or published and are therefore not included in this summary.

Project overview

The project is located at Phillip Island, located about 120 km south-east of Melbourne. The area is managed by Phillip island Nature Parks and Bass Coast Shire Council (60% agriculture, 20% urban, 20% conservation reserves). The Bass Coast Landcare Network undertakes conservation projects on the island. The population of Phillip Island has doubled over the past two decades to more than 10,000 permanent residents. The area is extremely popular for tourists, in 2014 it was found that over 1.85 million visitors came to Phillip Island each year. The combined increase in human activity poses a real threat to wildlife attempting to move throughout the landscape.

Roadkill is significant

Christine spoke about the issue of roadkill in Victoria.

Christine discussed a range of road crossing options and pointed out the costs involved in construction of crossing structures. Building high fences along roads is not really feasible due to funnelling of wildlife and creating problems at the end of the fence. Virtual fencing has the potential to allow the movement of wildlife across the road whilst only being a deterrent when a vehicle is present.

Virtual fencing

Virtual Fencing is an active electronic protection system that alerts animals before crossing the road when a vehicle is approaching between dusk to dawn. It comprises sensors placed at 25-meter intervals on alternate sides of the road which have coloured flashing lights and sirens, these are activated when a vehicle approached. The lights and sound are directed towards the edge of the road away from the vehicular surface. The alert to wildlife occurs so as to deter wildlife from the road before the vehicle arrives thus avoiding a collision.

The equipment used in the research is from Wildlife Safety Solutions https://www.wildlifesafetysolutions.com.au/

Christine spoke about some of the published literature regarding virtual fencing monitoring. Overall, the results look promising with a 50% reduction in roadkill in a Tasmanian study. Longer-term monitoring with before and after data is required to assess the effectiveness of this technology over time.

- Roadkill mitigation: trialing virtual fence devices on the west coast of Tasmania Samantha Fox A B D , Joanne M. Potts C , David Pemberton A and Dale Crosswell, Australian Mammalogy 41(2) 205-211 https://doi.org/10.1071/AM18012: November 2018.

- Roadkill mitigation is paved with good intentions: a critique of Fox et al. (2019) Graeme Coulson A C and Helena Bender B., Australian Mammalogy 42(1) 122-130 https://doi.org/10.1071/AM19009: 27 June 2019.

- Virtual fence devices – a promising innovation: a response to Coulson and Bender (2019) Samantha Fox A B D and Joanne Potts C., Australian Mammalogy 42(1) 131-133 https://doi.org/10.1071/AM19031: 1 July 2019.

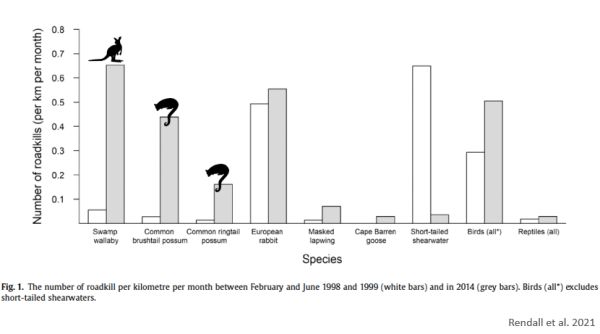

Analysis of Phillip Island roadkill

The level of roadkill on Phillip Island has increased from 1.95 roadkill/km/month in the 1990’s to 2.39 roadkill/km/month in 2014. The increase is attributable to an increase in road speed limits around the 60 to 80 km/hr. Roadside vegetation could be influencing roadkill for some species but more research is required to verify the relationship between vegetation complexity and roadkill.

Christine pointed out that on Phillip Island, Swamp Wallaby is the highest number in roadkill. Swamp Wallabies are a widespread species which favour sites where they can retreat into vegetation cover. They are diurnal (active during the day) but tend to move into more open areas at night often crossing roads and return to cover during the day. Water sources near roadsides tends to increase the movement of wallabies across roads.

Christine also pointed out there has been an increase in the Swamp Wallaby population on Phillip Island which is most likely due to the complete removal of foxes since 2017.

Study site and design

The study is being conducted on the Cowes - Rhyll Road which has an 80 km/h speed limit. It has been identified as a roadkill hot spot. There is habitat for wildlife either side of the road.

The project was initiated by Ron Day, a local resident and citizen scientist who approached the Bass Coast Shire about his concerns at the amount of roadkill. The Bass Coast Shire has since funded the 3-year trial on virtual fencing.

Christine explained the study includes a before / after control at multiple sections of the road which is necessary to determine the effectiveness of the virtual fencing. Surveys of roadkill are carried out 2-3 times /week.

Virtual fencing and control sections are used at selected sections of the road and will be relocated to a new location each year. After 2 years of surveys 364 surveys have been completed with 650 roadkill instances covering 21 species. The highest number of roadkill are Swamp Wallaby (265).

As the study is still underway it is not possible to present further data in this summary.

Key points from questions

- There are many opportunities for further studies into virtual fencing, e.g., using more natural defence sounds used by animals, habituation to sounds, measuring disturbance to other species etc.

- Marsupials have different eye structures to humans so the type of wavelengths of light in any deterrent device needs to be considered.

- After the third year, results from the trails will be made available.

See also on the SWIFFT web site: