SWIFFT Seminar notes 31 October 2024

New discoveries and methodologies

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 110 participants via Microsoft Teams. SWIFFT wishes to thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Also, thanks to Craig Whiteford, Zoos Victoria, who chaired the session and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

This seminar helped to raise awareness of new discoveries and methodologies in the conservation of threatened species by Zoos Victoria and the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria.

Key points summary

Applying wildlife detection dogs to fungal conservation

- Wildlife detection dogs have been trained by Zoos Victoria to use their sense of smell to help conservationist understand what species are in the environment. But this is the first time a detection dog has been trained to detect a critically endangered Tea-tree fungus.

- The Tea-tree fungus is a parasitic wood rot fungus found mainly on tea-tree and melaleuca species in old and established unburnt habitat.

- It is very difficult to visually survey Tea-tree fungus, but using a trained dog and handler has proven to be far superior both in terms of time and number of detections compared against known survey methodologies.

- The specially trained detection dog was able to find Tea-tree fungus down to the size of half a grain of rice.

A brief look at some recent plant discoveries and re-discoveries in Victoria

- The National Herbarium of Victoria is the oldest scientific institution in Victoria. The herbarium contains the largest collection of dried plant, algae and fungi in Oceania, comprising 1.562 million specimens.

- The overall trajectory for native plants in Australia is not good with 1,426 of Australia’s plant species listed as at risk of extinction and 36 species now extinct. There are 1,617 species listed as threatened in Victoria.

- A great deal of flora survey work was carried out as part of reassessments of areas which had been burnt in in 2019/20 East Gippsland fires and the 2022 Murray River floods.

- Increased survey effort has been fundamental in rediscovering / discovering some of Victoria’s threatened plants. It is important that surveys are carried out at the right time as many fire related species would not be found and their status indeterminate.

Conservation of Victoria's fern diversity through cryopreservation of spores

- The Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria undertakes conservation of threatened species of ferns and lycophytes which can involve the collection and preservation of their spores in long-term storage (Spore Bank). The spores can be used at a later date for reintroductions and producing plants for cultivated collections.

- There are 123 native fern and lycophyte species in Victoria (25 % of Australia’s native fern and lycophyte species), 39 Victorian fern and lycophyte species are rare or threatened and only one species of fern Isoetes pusilla is endemic in Victoria.

- The initial target for the spore bank is to have enough genetic diversity collected from 72 species of ferns from Victoria.

Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon: a rare second chance

- For the first time in the history of earth the unfolding mass extinction event is being caused by humans, referred to as the Anthropocene biodiversity crisis.

- The last confirmed record of the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon was 1969 after which time it was presumed extinct until rediscovered in January 2023.

- The main reason why VGED went from being relatively common in its specific habitat to being undetectable is habitat destruction and habitat loss, particularly the grasslands west of Melbourne.

- The Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon Recovery Team was formed to protect and manage the last known population now confined to a small area in just four paddocks.

- A conservation breeding program at Melbourne Zoo was able to produce 50 new dragons in the first year.

- Great caution is needed when interpreting surveys for the VGED or potential habitats, particularly if destruction is planned e.g., land development. Taking a precautionary approach is essential.

List of topics and speakers

- Applying wildlife detection dogs to fungal conservation - Nick Rutter - Wildlife Detection Dog Officer, Zoos Victoria

- A brief look at some recent plant discoveries and re-discoveries in Victoria - Andre Messina - Botanist, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria

- Conservation of Victoria's fern diversity through cryopreservation of spores: introducing the RBGV Victorian Cryopreservation Bank - Daniel Ohlsen - Botanist, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria

- Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon: a rare second chance - Nick Clemann – Senior Biologist Herpetology

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Applying wildlife detection dogs to fungal conservation

Nick Rutter - Wildlife Detection Dog Officer, Zoos Victoria

Nick introduced his presentation by pointing out the project is a collaboration between Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria and Zoos Victoria.

Nick acknowledged both the Bunurong people and Wurundjeri people, custodians of the lands and their deep connection to the lands and waters, where much of the project was carried out.

Use of wildlife detection dogs

Wildlife detection dogs have been trained to use their sense of smell to help conservationist understand what species are in the environment. The dogs can be trained to detect a particular species. Zoos Victoria detection dogs are used in the conservation of Zoos Victoria fighting extinction high priority species, which can include mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians.

Zoos Victoria detection dogs’ team was set up in 2020. There are 3 wildlife detection dog officers at Zoos Victoria.

This project is the first time a dog has been trained to detect fungi – in this case, the Critically endangered Tea-tree fungus.

Tea-tree fungus

Nick provided an overview of the Tea-tree fungus but pointed out the speciality regarding fungi is with the Royal Botanic Gardens. His role is the training of the dog to detect the fungi.

Conservation status: Critically endangered

Distribution: Bass Coast area with recently discovered sites in the Yarra Ranges and also the Otways.

Population: only about 200 individual fungi known to exist

Threats: Land clearing, warming drying climate, requires old and established unburnt habitat

Training 'Daisy’

Nick spoke about the training of one of the detection dogs called Daisy, a Labrador who received specialist positive reinforcement training which uses the odour of the particular species combined with reward (e.g. food). The issue for Nick was that Tea-tree fungus has a low odour volitility which meant the detection required training for fine scale searching down to 50 cm. Nick pointed out it is very much about forming a specialised dog and handler relationship.

Testing to see if Daisy could detect Tea-tree fungus in the wild was carried out prior to being deployed on surveys. In addition, performance assessment was carried out to rate the level of detection using Daisy and handler compared against known survey methodologies. It turned out that Daisy is a star in detection of Tea-tree fungus and far superior to any other known survey methods, both in terms of time and number of detections.

The highest detection accuracy, up to 95% accuracy is obtained when a dog/handler team is used in conjunction with an expert human surveyor.

Knowing if Tea-tree fungus is present or not can be a major step forward in effective management of areas, particularly with regards to fuel reduction burning. By knowing Tea-tree fungus is not present, burns can be undertaken knowing there are no conservation issues for this species.

Nick discussed the potential of using detection dogs in the conservation of other fungi.

Open access study

On the trail of a critically endangered fungus: A world-first application of wildlife detection dogs to fungal conservation, Michael D. Amor, Shari Barmos, Hayley Cameron, Chris Hartnett, Naomi Hodgens, La Toya Jamieson, Tom W. May, Sapphire McMullan-Fisher, Alastair Robinson, and Nicholas J. Rutter, iScience 27, 109729 May 17, 2024.

Nick thanked all the collaborators involved in the project.

Key points from questions

- There are a couple of types of host fungus which Tea-tree fungus parasitises.

- The Tea-tree fungus host fungi is relatively common but this does not mean TTF will be present.

- Tea-tree fungus tends to be found from the ground level to about chest height.

- There may be an application for using eDND to detect TTF in air samples or taking swabs from particular plants.

- Habitat type and weather conditions can play a significant role in the capability of detection dogs to detect their target. Closed vegetated habitat is easier to work in compared to open grassland habitat.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

A brief look at some recent plant discoveries and re-discoveries in Victoria

Andre Messina - Botanist, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria

Andre acknowledged the Traditional Owners of the Wurundjeri People from where he was presenting.

Andre introduction his presentation by talking about the National Herbarium of Victoria which is the oldest scientific institution in Victoria, being founded in 1853. The herbarium contains the largest collection of dried plant, algae and fungi in Oceania, comprising 1.562 million specimens. The collection includes over 30,100 types, which is the largest repository of type materials in the Southern Hemisphere.

Conservation trends for Australian plants

Andre spoke about the fact that the overall the trajectory for native plants in Australia is not good:

- 1,426 of Australia’s plant species are listed as at risk of extinction

- 36 species have become extinct

- 1,617 species listed as threatened in Victoria

Climate change, extreme weather events, fire and floods are thought to be some of the major contributing factors for future losses

Recent finds following fires and floods

Andre discussed some of the survey work carried out as part of reassessments of areas which had been burnt in in 2019/20 East Gippsland fires, funded through the Victorian Government Bushfire Biodiversity Response and Recovery project. Andre highlighted the importance being able to conduct surveys and the fact that the increased survey effort has been fundamental in rediscovering / discovering some of Victoria’s threatened plants.

Post disturbance ephemeral species

Andre spoke about some examples of surveys which are carried out to confirm the presence of threatened flora which only appear after fire. Unless surveys are carried out at the right time many fire related species would not be found and their status indeterminate.

Actinotus forsythia (Pink flannel flower) – critically endangered, single population in Victoria, plants appear en masse then disappear until after the next fire.

Irenepharsus magicus (Elusive Cress) – endangered, restricted to Alpine Ash and montane woodland in areas east of Omeo, abundant following disturbance such as fire or forestry operations, only observed one-two years post disturbance.

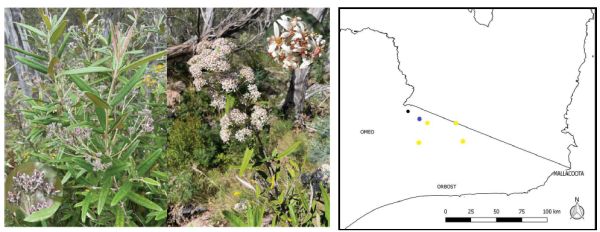

Haloragodendron baeuerlenii (Shrubby Raspwort) - endangered in Victoria, restricted to steep gorge country in eastern Victoria, seen in low numbers in absence of fire but abundant following fire.

Commersonia species

Andre spoke about four species:

Commersonia prostrata – numerous records from West Gippsland, observed in the absence of fire.

Commersonia dasyphylla – 3 records, Murrindal and ‘Buffalo Ranges’

Commersonia breviseta – 1 record near Genoa Peak

Commersonia rugosa - new discovery in far eastern Victoria. As a result of surveys conducted after the 2019/20 bushfires a fourth species was discovered at a single site in far eastern Victoria. This species is regarded as being widespread but not common in NSW. It has been only been recorded in Victoria once or twice in the last 150 years.

Commersonia rugosa – a new species discovered in Victoria’s far east. Note the long fruits (inset top left).

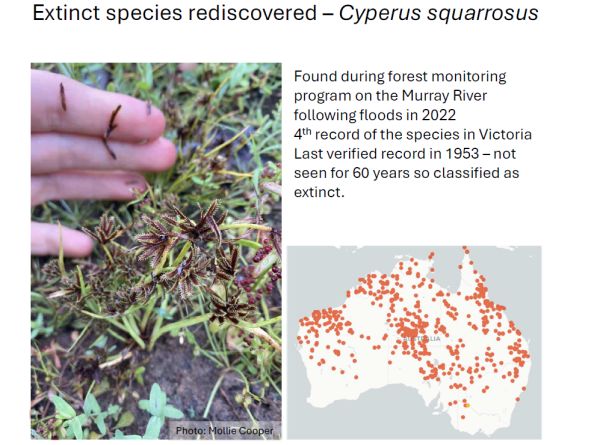

Extinct species rediscovered

Species confirmed in Victoria – Olearia aglossa

Andre pointed out that the rediscovery of Olearia aglossa is only the second verified record of this species in Victoria since the 1850’s. Olearia aglossa was rediscovered during a BushBlitz Species Discovery expedition in the Alpine National Park 2022.

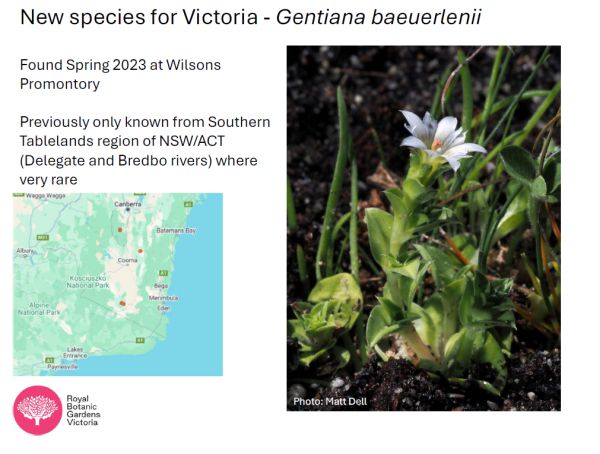

New species for Victoria - Gentiana baeuerlenii

INaturalist

Andre spoke about the value of Citizen Science in building knowledge about the distribution of flora. He used an example of Dwarf Violet Viola improcera which was previously only known from southern NSW and far east Victoria but discovered in Tasmania.

Key points from questions

- The discovery and rediscovery of species would not have been possible without a substantial survey effort and verification of specimens.

- Andre has been able to use records from INaturalist to assist him in the verification of sites where particular species can be found for the purpose of seed collection.

- INaturalist records can provide valuable information on when a particular plant is flowering and fruiting. It also provides an avenue for people to add records on private land which is often not well surveyed.

Related topic: East Gippsland range restricted flora

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

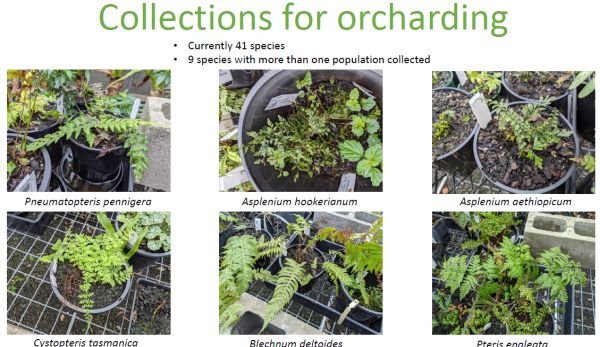

Conservation of Victoria's fern diversity through cryopreservation of spores: introducing the RBGV Victorian Cryopreservation Bank

Daniel Ohlsen - Botanist, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria

Daniel presented from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne and acknowledged the Traditional Owners of the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Country.

Overview of ferns and lycophytes in Victoria

Daniel spoke about the difference between ferns and lycophytes:

- Ferns reproduce by spores produced on the undersides or margins of leaves unlike seed plants

- Lycophytes (clubmosses, Selaginella, Isoetes) reproduce by spores produced in cones, near stem apices or in dilated leaf bases. They are a separate linage of plants that reproduce by spores but also have a complex vascular system

Victoria has 123 native fern and lycophyte species (25 % of Australia’s native fern and lycophyte species). In Victoria, 4% of the vascular plant species are ferns and lycophytes.

There is only one species of fern Isoetes pusilla which is endemic in Victoria, this is a very low number when compared to flowering plants of which 8% are endemic to Victoria. Daniel pointed out that ferns and lycophytes generally have wider distribution than flowering plants because spores from ferns and lycophytes are small and have a much higher propensity to disperse on air currents than seed plants.

39 Victorian fern and lycophyte species rare or threatened in Victoria.

(Left) Pneumatopteris pennigera Lime Fern – Endangered

(Centre) Adiantum formosum Black Stem - Critically endangered

(Right) Phlegmariurus varius Long Clubmoss – Critically endangered

Ex situ conservation of fern and lycophyte species

Daniel spoke about the need to undertake conservation of threatened species of ferns and lycophytes which can involve the collection and preservation of their spores in long-term storage. The spores can be used at a later date for reintroductions and producing plants for cultivated collections.

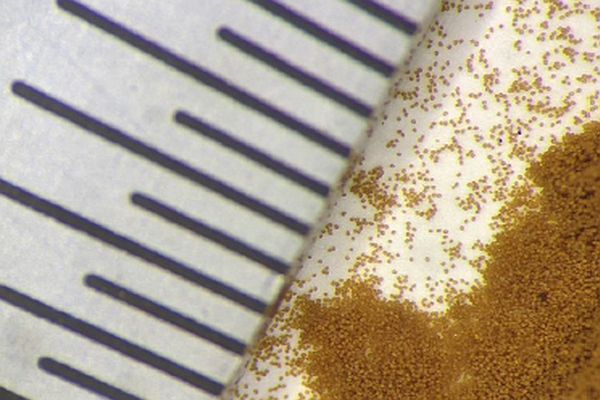

A spore bank can be used to store a large number of spores in the millions in a small space because the size of the spores is so minute (mostly 25–55 micrometer μm, in size). Because so many spores can be stored it also helps capture the genetic diversity of the species.

Threats to conservation of ferns

Daniel spoke about ongoing threats to ferns, particularly as they occur in moist vegetation types and are particularly vulnerable to disturbance from fire and impacts from drought.

The number of spore banks has lagged behind seed banks. There are about 1,500 seed banks worldwide but less than 10 spore banks worldwide with most of the spore banks used for research into fern spore viability and preservation rather than being used to bank as many fern species as possible.

Sampling methods

Daniel spoke about the process and thought behind collecting samples for the spore bank. The aim is to collect from natural populations throughout their range for both widespread and common species initially for 10–20 populations.

For some of the species there is already an understanding of their genetic diversity throughout Victoria which helps to ensure samples include as many genetic linages as possible for the spore bank.

The initial target for the spore bank is to have enough genetic diversity collected from 72 species of ferns from Victoria.

Collecting spores

Daniel pointed out that collections of live ferns increase the known provenance in the gardens and have a source of preservation in live plants which could be used to provide stocks for reintroduction into the wild if required.

Processing spores

Daniel spoke about the processing of spores once they are collected, the equipment used to sieve out unwanted material and the drying and packing of spores. Once prepared for storage the spores are packed in foil parcels, labelled, placed inside eppendorf tubes, then placed into boxes for long-term storage inside a -150˚C Arctiko CRYO230 electric freezer. Daniel explained that for most species of ferns the spores only remain viable for a short time at room temperature, even at low temperatures in a standard freezer their viability decreases over time. Therefore, the best type of long-term storage is using a cryogenic freezer. There are currently 25 Victorian species with spore samples banked in the freezer.

There are four methods which can be used to germinate spores:

1. on agar in a growth cabinet (orthodox method)

2. on Dicksonia antarctica tree fern slabs in a terrarium

3. on Dicksonia antarctica grounded up into a fine medium in sealed container in growth cabinet

4. on Peat in sealed container in growth cabinet

Methods 3 and 4 have yielded the best results from trials.

Future extensions

Daniel spoke about applying the research to cultivating other species of ferns which have proven difficult to cultivate. There are also opportunities to apply learnings to storage and cultivation of bryophyte spores, fungal tissue, pollen and non-orthodox seeds which need to be stored at very low freezing temperatures.

Daniel acknowledged contributors to the project which was primarily funded through DELWP Bushfire Recovery funding.

Key points from questions

Some species of fern spores can remain viable at room temperature (generally species that live in dry environments) but more sensitive species have a short viability. Daniel stressed that the viability time really depends on the species concerned.

VicFlora has information on all the fern species in Victoria. VicFlora - ferns

Ferns can be seen in many parts of Victoria, even in dry places where they can be found in moist rock crevices. Higher diversity of ferns occurs in higher rainfall areas.

It is uncommon for ferns to form mycorrhizal connections but some Families such as Gleicheniaceae, Lindsaeaceae, Schizaeaceae have mycorrhizal associations.

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon: a rare second chance

Nick Clemann – Senior Biologist Herpetology

Nick represented the Recovery Team for the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon. Nick presented from Zoos Victoria and paid his respects to the Wurundjeri People.

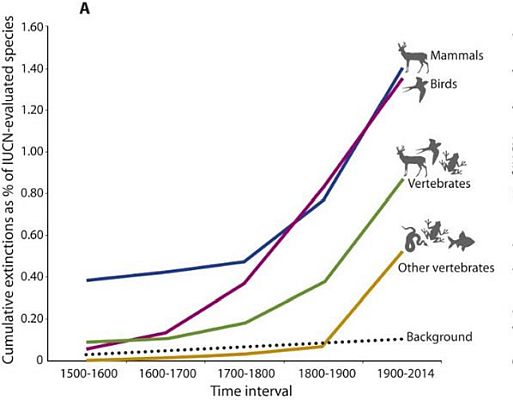

Mass extinction events

Nick spoke about the history of five mass extinction of life events on earth over deep time dating back to the Ordovician – Silurian period around 445 million years ago. During the Permian extinction event around 252 million years ago referred to as the ‘Great Dying’ 95% of life on earth was lost.

Nick spoke about publications suggesting we could be entering the 6th mass extinction event on earth. More information BBC

Nick felt that in any event we are certainly entering a period of biodiversity crisis.

Decline of reptile fauna in Victoria

Nick realised the significance of the decline of reptiles in Victoria some years ago and wrote a paper titled Cold-blooded indifference: a case study of the worsening status of threatened reptiles from Victoria, Australia CSIRO Publishing Pacific Conservation Biology, 2015, 21, 15–26

Extinction rates since the industrial revolution

Nick spoke about the default rate of extinction which is the natural rate of loss over time as species generally do not last forever. The problem is that there has been a significant rate of increased extinctions, 1,000 times more than the default rate since the industrial revolution.

Nick emphasised that for the first time in the history of earth the unfolding mass extinction event is being caused by humans, referred to as the Anthropocene biodiversity crisis. At this point in human history, we not only have a self-induced biodiversity crisis but we also have a climate crisis.

Nick spoke about the concept of Eco-grief, the realisation that we are losing so much of nature which can manifest itself as a form of numbed apathy. The alternative is to step up and take action. Thankfully, there are many examples of species being saved with good reason to save more species such as the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon which until recently was thought to be extinct.

Nick spoke about the early records of the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon (VGED) from 1894 through to the 1920’s which identified it as only occurring in a particular range, in a certain type of grasslands, not widespread but not uncommon to observe. However, as time passed this species was thought to be extinct as the last confirmed record was near Geelong in 1969. Despite numerous dedicated surveys since 1970 by many specialist herpetologists there was no sign of the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon until rediscovered in January 2023.

Threats

Nick pointed out the main reason why VGED went from being relatively common in its specific habitat to being undetectable is habitat destruction and habitat degredation. In particular, the grassland habitat west of Melbourne has dramatically changed through direct clearing associated with land development. Only fragmented patches of habitat remain and these are often modified through increased biomass of grasses and weeds, the loss of rocky refuges due to the removal of basalt rocks over the years and changed grazing regimes.

Relentless survey effort

Nick spoke about the hope that existed by some herpetologists that the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon could still be found by conducting pre-development surveys on potential habitat at land earmarked for development. In January 2023, a pre-development survey found a Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon. Nick explained that the survey comprised the use of about 250 roof tiles which were surveyed 8 times, thankfully one VGED was found in the last survey.

Recovery Team

Due to the significance of the re-discovery a Recovery Team was very rapidly formed comprising members who are very knowledgeable on the species and conservation actions required.

Survey methods

Nick outlined the methods used to carryout surveys, which is mainly focused on the inspection of spider burrows, being a key refuge for the dragon. Artificial spider burrows are also used to attract the dragon. Roof tiles are used as part of a standard grassland fauna survey method. Small pitfall traps are used but only when scientists are on-site.

Nick stressed that because the dragon’s are so difficult to survey and detect a great deal of caution is needed in interpreting surveys where no detections are found.

Research and biology

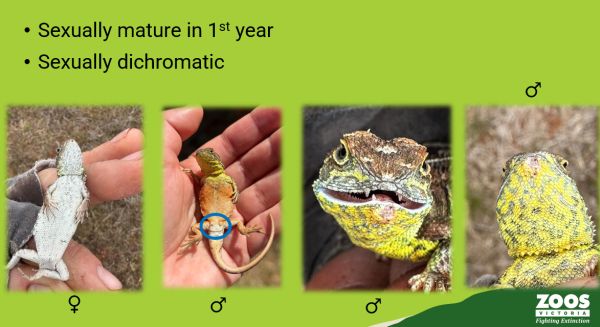

Nick spoke about some of the research findings. It is now known that the VGED is sexually mature in the first year. They are also sexually dichromatic (males and females can look quite different during the breeding season with adult males displaying orange, predominantly in the autumn and spring).

Well camouflaged - Nick described how difficult it is to observe a dragon once it is on the ground as it blends in extremely well.

Results from the first year of the recovery project:

- 80 unique dragons detected (across 4 adjoining paddocks)

- More than 30 founders were collected for the Melbourne Zoo Conservation Breeding Program

- Genetic analyses - undertaken by Museums Victoria

- Monthly spider burrow counts carried out as spider burrows form a critical component of the habitat

- Invertebrate studies / monitoring – Invertebrate diversity can be a specific factor in the dragon’s occupancy

- Diet studies (to determine if the dragons are selective in their dietary patters, comparing available food verses eaten invertebrates)

- Botanical surveys / monitoring

- Habitat modelling More information: Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon habitat distribution model (DEECA)

Captive breeding

Nick emphasised the importance of not only doing field-based monitoring and management but combining these activities with a conservation breeding program at Melbourne Zoo.

An update on the 2024 breeding season, as at 31 October 2024 there are 14 breeding pairs which have produced 9 clutches of eggs and 9 hatchlings from 2 of the clutches which means the second breeding season looks very promising with similar results to the first year.

Managing grassland habitat

Nick discussed the importance of managing VGED grassland habitat to optimises their chances of success. An important element is to ensure the native grass does not grow too much and smother out the habitat. Therefore, in the absence of native fauna it is important to implement a means of reducing the biomass through carefully managed grazing using sheep. Too much grass is detrimental, too little grass is also detrimental so it is very important to carefully manage the level of grazing to suit the earless dragon.

Because the VGED is so critically endangered the management regime at this site needs to cater specifically for this species.

Challenges ahead for the Recovery Team

A very high priority is to secure the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon within the four paddocks at the discovery site.

There are difficulties in accessing nearby properties containing potentially suitable VGED habitat which means the opportunity to carry out formal dragon surveys is limited. Nick stressed that the future for the VGED cannot be confined to just four paddocks, so finding any other nearby populations and areas of suitable remnant habitat is important.

Zoos Victoria are funding current recovery efforts but with limited funding more funding is required to fully secure the dragon’s future.

Great caution needed when interpreting surveys for the VGED or potential habitats, particularly if destruction is planned e.g., land development. Taking a precautionary approach is essential.

Verifying information about the VGED via the Recovery Team is essential as there is a need to avoid any mistruths regarding the status of this species, its habitat and conservation needs from uninformed or dubious sources.

Help support recovery of the Victorian Grassland Earless Dragon – buy a tote bag from Zoos Victoria

Key points from questions

The risk of missing a VGED in a survey is high. Even knowing where they are, sometimes months can pass without a detection so interpreting a single survey with no detection is very risky. Therefore, if it is within a known area with suitable habitat parameters the precautionary approach would be to assume presence.

Reducing grassland biomass through cool burning could be an option but too risky at present given the small area / population involved. It is known that careful grazing using sheep works so this is the preferred method for habitat management at present.

The reintroduction of VGED is part of the recovery effort but suitable habitat must be found and remain secure. The habitat tends to be very specific and a combination of factors needs to be carefully assessed. Just because it is a Volcanic Plains grassland does not necessarily mean all the other habitat components will be suitable.

The Recovery Team is interested to hear from contacts who have potentially suitable habitat already under protection.

View notes from previous SWIFFT seminars