Video conference notes 31 October 2014 - Wetlands

SWIFFT video conference notes are a summary of the video conference and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This video conference was supported through resources and technology provided by the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Victoria. SWIFFT wishes to thank speakers for their time and delivery of such excellent presentations.

The fourth and final video conference for 2014 had a theme on Wetlands and Waterways. A total of 69 participants were connected across 12 locations; Ballarat, Bendigo, Colac, Geelong, Hamilton, Heidelberg (Arthur Rylah Institute), Heywood, Horsham, Melbourne (Nicholson Street), Traralgon, Warrnambool, Wodonga.

List of groups/organisations in attendance;

- Educational: Federation University Australia, Bendigo TAFE

- Local Government: City of Wyndham, Baw Baw Shire, Latrobe City, Colac Otway Shire.

- Field Naturalist Clubs: Ballarat, Geelong, Hamilton, Portland.

- Community Conservation Groups: Windamara Aboriginal Corp., Geelong Environment Council, Friends of Eastern Otways, Land for Wildlife, Ballarat Environment Network, Garabaldi Landcare.

- Conservation Organisations: Parks Victoria, Nature Glenelg Trust, Trust for Nature, , North East CMA, North Central CMA, West Gippsland CMA, Glenelg Hopkins CMA, Corangamite CMA, Dept. of Environment and Primary Industries staff across 14 locations, inc. Nicholson Street Melbourne and Arthur Rylah Institute, Heidelberg.

- Industry: Environmental Justice Office Australia, Rakali Consulting, Central Highlands Water.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY Quick take home messages from this video conference or read through the speaker summaries.

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Restoring wetlands in the South West - Mark Bachmann - Manager, Nature Glenelg Trust

Mark spoke about recent case studies of restoring wetlands on private and public land in south-west Victoria.

About the Nature Glenelg Trust

Mark said the Nature Glenelg Trust (NGT) is a not-for profit organisation which undertakes grant funded biodiversity project delivery and professional consulting on projects related to habitat protection and restoration, with an emphasis on wetlands. The NGT focal region extends between Melbourne and Adelaide.

The NGT incorporates the use of sound science and conservation based research to enhance management outcomes. The NGT also seeks to involve the community in projects.

Why focus on wetlands?

Mark said wetlands are ecologically significant and also support a diversity of threatened species. Wetlands are important in terms of providing environmental services, for example, clean water, flood buffering and aquifer recharge. Wetlands provide beauty and athletic values to landscapes as well as recreational opportunities. Wetlands also have many times the carbon storage potential per unit area when compared to terrestrial soils.

Wetlands were once a highly prominent feature of the landscape but the loss of wetlands has been dramatic with 90 -95% drained in the south-east of South Australia and over 60% drained in the Glenelg Hopkins region of Victoria.

In terms of restoration, wetlands are highly adaptive ecosystems which depending on the circumstances can have a capacity for rapid restoration and recovery potential.

Threats

Ongoing land use threats include; forestry establishment, conversion to more high use water land uses e.g. irrigated agriculture, groundwater extraction, diversions.

Nature Glenelg Trust wetland restoration - case study sites

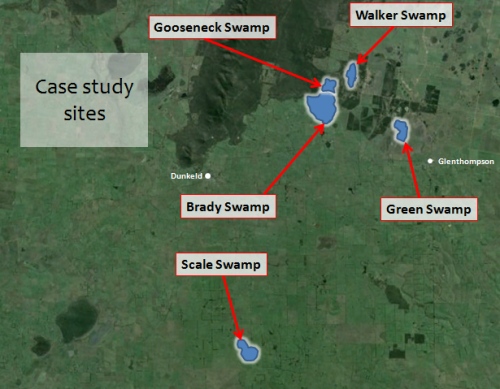

Mark said there have been about 20 wetland restoration sites in south-west Victoria. Mark spoke about five case study sites in the southern Grampians, upper Wannon River area.

- Scale Swamp - private property, highly modified.

- Green Swamp - part private, part public land, partially modified.

- Brady, Gooseneck and Walker Swamps (trial management solutions) - part private with multiple stakeholders, part public land, partially in a declared drainage scheme area, partially modified.

At each site there was landholder support for restoration works. GNT worked closely with landholders and the community to develop sustainable wetland restoration outcomes.

Planning tools

Mark explained that GNT thoroughly researches historical information and past references to gain an understanding of what a particular wetland would have looked like and what drainage/diversion works were carried out in the past. This is important background work before developing restoration plans.

Collecting data from old air photos can be helpful in understanding landscape changes

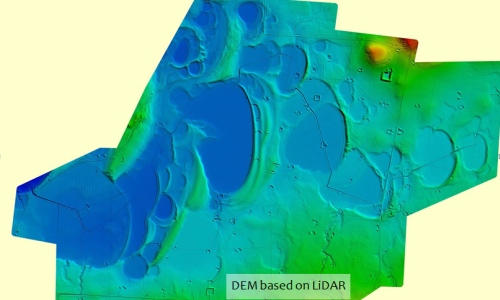

The use of LiDAR technology to build a digital elevation model is very useful in displaying where water would go at different elevations. This is important in determining the expected inundation zone and works needed to restrict outflows and setting spill levels.

The NGT is able to work across state borders and different land tenures which means they can adapt and apply knowledge gained from previous projects.

Mark said allocating time to gather history and data about the wetland and applying new mapping technologies is an essential part in wetland restoration planning. Building lasting relationships with landholders and the community is very important, in terms of planning, works and on-going monitoring.

Works

Some of the restoration works are as simple as blocking drains. At other sites levee structures with spillways were built to manage water levels. At the Brady, Gooseneck and Walker Swamps a trial wetland restoration approach was taken which incorporated semi-permanent and easily adaptable geo-fabric sandbag structures which can be adjusted. If trials prove successful more permanent measures can be taken, which is the case for Brady and Gooseneck Swamps in 2015.

Mark spoke about the fact that on many flat wetlands even small changes to the structure height can make a significant difference to the area of wetland retained and extending the time of inundation thereby having a significant impact on increasing biodiversity values.

A key feature of the wetland restoration process is to involve the community and have a shared interest in the projects.

Hydrological monitoring

At some wetland restoration sites data loggers are used to track water flow and elevation.

Ecological monitoring

Depending upon the site, ecological monitoring is carried out to various levels. Monthly bird monitoring counts are undertaken at the trial sites by the Hamilton Field Naturalists Club. Fish surveys and the use of frog recorders are also used along with vegetation monitoring to measure floristic change.

Mark gave a special thanks to the private landholders of the Case Study sites presented along with Hamilton Field Naturalists Club, Parks Victoria, Department of Environment and Primary Industries, Australian Government and the Glenelg Hopkins CMA.

Key points from questions

- Getting accurate facts on the table and building relationships is fundamental to gaining landholder support for projects.

- Formal tenure management agreements are entered into prior to restoration works.

- In some cases risks are only perceived risks that might never eventuate or the risks insignificant in terms of natural climatic variations.

- NGT hopes that by working with people who want to see a change in the way we appreciate and manage wetlands it might serve as a catalyst to get other people thinking about wetlands and the need to protect and restore them.

- Grazing on wetlands needs to be determined on a case by case basis. Some sites can tolerate managed seasonal grazing which can be beneficial but each wetland needs to be considered on an individual basis.

- There are cases where planting fringing vegetation with species such as such rushes, sedges and tangled lignum could assist to speed up restoration.

A public open day to demonstrate wetland restoration will be organised for Gooseneck Swamp on 23 November 2014.

Contact: Nature Glenelg Trust, Mount Gambier Office Ph. 08 8797 8596

Manager, Mark Bachmann 08 8797 8181

Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains - the South Australian experience - Cath Dickson, Threatened species flora ecologist, Nature Glenelg Trust.

Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains are one of our Nationally listed communities and Critically endangered under the EPBC Act 1999. The listing was completed in March 2012 and was a combination of the Temperate Lowland Plains Grassy Wetlands and the Victorian Volcanic Plains Freshwater Swamps EVC's.

Cath's work was undertaken as a contract for Natural Resources – South East (Department of Environment, Water & Natural Resources). The project had a State-wide Technical Reference Workshop. Its aim was to plan and undertake surveys of Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (SHW) in South Australia and provide advice on their condition, current and future management.

Characteristics of Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains

Survey results

A total of 174 wetlands were assessed using the criteria formulated for this type of wetland. 79 wetlands did not meet the criteria. 77 were assessed as meeting the criteria for listing (54 of these being assessed as high value). The remaining 18 wetlands were either too small of low quality.

The validation of wetlands found the area of occupancy of the intact wetlands was only 563.12 ha from the predicted 7,296ha total in the listing. This means the situation is much worse than originally estimated. It was also found that over 70% of SHW are less than 5 ha.

Cath spoke about describing different types of Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands and grouped them into six main types which are summarised below and described in the final report. Full descriptions, Dickson et al. 2014.

| 1. Seasonal Herbaceous Wetland - The most common of the wetlands; Fringed by Red Gums Eucalyptus camaldulensis and containing Amphibromus spp., Ornduffia reniformis, Potamogeton spp., Montia australasica, +/- Allittia cardiochila +/- Eryngium spp. |  |

| 2. Seasonal Herbaceous Grass/sedge Wetland - Emergent / isolated fringing Eucalyptus camaldulensis, pockets of Carex tereticaulis +/- Eleocharis acuta +/- Glyceria australis +/- Lachnagrostis spp. +/- Amphibromus spp. +/- Triglochin spp. |  |

| 3. Seasonal Herbaceous Grass/sedge Wetland - Fringing / overstory +/-Eucalyptus. camaldulensis, Glyceria australis +/- Amphibromus spp. +/- Lachnagrostis filiformis, Montia australasica +/- Triglochin spp. |  |

| 4. Seasonal Herbaceous Wetland - Fringing Overstorey or Emergent Species Eucalyptus leucoxylon +/-Callistemon rugulosus, +/- emergent Eucalyptus. camaldulensis with Amphibromus spp., +/- Chorizandra enodis, +/- Craspedia paludicola Rytidosperma duttonianum. +/- Ornduffia reniformis +/- Utricularia spp. |  |

| 5. Gilgai Seasonal Herbaceous Grass/sedge Wetland Mosaic-Fringing Eucalyptus camaldulensis, +/- Allocasuarina luehmannii +/- Duma (syn. Muehlenbeckia) florulenta containing Amphibromus spp., Eleocharis acuta, +/- Swainsona procumbens, +/- Craspedia paludicola, +/- Schoenus tesquorum |  |

| 6. Seasonal Herbaceous Wetland - Triglochin procera, Montia australica, Potamogeton spp. Myriophyllum spp. +/- Ornduffia reniformis |  |

Management recommendations

Of the 77 wetlands identified as meeting the listing criteria 59 had degraded buffers with grazing and pugging causing damage. Weed control was identified as the major action for most sites followed by altered stocking regimes. Managers need to be aware of the difference on wetland ecology between grazing cattle compared with sheep and the different times of grazing. There are examples where more true to form herbaceous vegetation exists on sheep grazing sites compared with cattle grazing.

Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands are very dynamic with and are highly influenced by management and therefore require periodic reassessment. Even in cases where passive management is applied changes to plant community structure can occur. Changes to groundwater and surface water movement can also have a dramatic impacts on these types of wetlands and their classification.

There is a need to review the EPBC listing definitions of Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands because the systems are so dynamic in their response to climatic conditions.

Future directions

- Natural Resources – South East are undertaking a management actions;

- Fencing

- Seasonal summer grazing and managed grazing intensity

- Weed control

- NGT 2014 survey fFocusing on Bool Lagoon and Dismal Swamp Complexes and refine vegetation description

- Update Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands State-wide layer

- If a wetland has been cropped and intensively used in the past it is disqualified from the EPBC listing process.

- There are cases where previously cropped sites can recover. The assessment process needs to take this into account along with changes which can occur depending upon different annual climatic conditions, e.g. wet summers, dry summers.

Contact: Cath Dickson, Glenelg Nature Trust, 08 8797 8596, Cath.Dickson@natureglenelg.org.au

See also:

- Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands, Species profile and threats database - Department of Environment

- Dickson C.R., Farrington L., & Bachmann M. (2014) Survey and description of the Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains in the South East of South Australia.pdf Report to Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia. Nature Glenelg Trust, Mount Gambier, South Australia.

Corner Inlet Connections - Matt Bowler, West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority

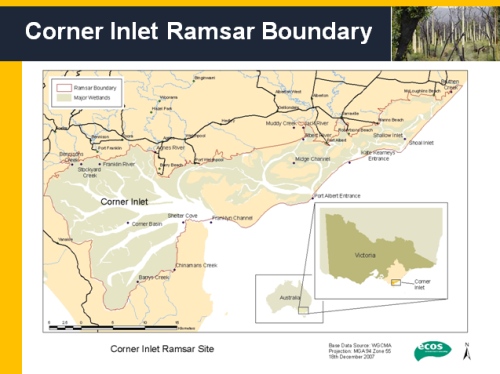

Matt explained the Corner Inlet Connections is a partnership project co-ordinated by the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority to protect the Corner Inlet Ramsar Wetland and the Nooramunga Marine Park.

Project partners include farmers, commercial and recreational fishers, landcare networks, EPA, local government and Parks Victoria. The Gunai-Kurnai and Boonwurrung people have strong cultural connections to region.

The project covers the catchment and all the waterways that flow into Corner Inlet and Nooramunga. The catchment contains highly productive plantation forest, dairy and grazing enterprises which ultimately influence the health of the marine ecosystem, particularly the sea grasses.

Matt spoke about the values of the inlet which contains a diverse range of habitats including fringing salt marshes, mud flats, deep channels, shallow seagrass beds, and barrier islands. These habitats support a diverse number of flora, fauna and fishes. The area is a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar convention, it is also a East Asian-Australasian Shorebird Network Site. The area contains the most southern occurrence of White Mangroves in Australia and contains a variety of seagrass communities including zostera, pyura and posidonia. The marine habitats support the third largest commercial bay and inlet fishery in Victoria.

Seagrass beds are a major feature of the marine environment

Barrier Islands protect the inlet from Bass Strait, these islands support a diverse range of flora and fauna.

The inlet's proximity and dependence on a healthy catchment requires support from all people in the catchment to reduce nutrient inflow into the system.

Management and restoration

The WGCMA has identified thirteen river catchments which have been broken down into 67 sub-catchments. Erosion and inflow of nutrients are a major focus of catchment management. The introduced Spartina is a major threat to mud flats and requires on-going control. Fencing to protect over 700ha of saltmarsh habitat has been achieved over the last 4 years. A major achievement has been the fencing and revegetation of the bottom 15 km of the Franklin River.

The health of the marine environment is directly influenced by catchment management.

Revegetation of streams to reduce run off and stabilise stream banks has been undertaken along with willow removal. Management has also focused on pasture management, nutrient application rates, dairy farm effluent collection, effluent management, tracks, crossings, wet area management, restoring bare areas and restoring landslips.

Project achievements

- Over 3500ha blackberry suppressed

- 150ha coastal woodland protected

- fox free activity on a number of the barrier islands

- 700ha coastal saltmarsh protected

- 150ha riparian restoration

- 100ha erosion control activity

Key points from questions

- The introduced Northern Pacific Starfish was recorded in the inlet in the past but was confined to a limited area by a series of freshwater pulses and controlled by direct removal by divers .

- The main control method for Spartina is spraying with Fusillade which is carried out under strict conditions. A monitoring area being conducted by RMIT to measure any impacts on macro invertebrates.

- The focus of effort is on estuaries where Spartina has not yet established.

- The use of conceptual diagrams to explain interaction within a landscape can assist in community education.

Contact: Matt Bowler, West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority, (03) 5175 7800

See also: Corner Inlet Connections

General discussion summary

- There are cases where planting fringing vegetation with species such as such rushes, sedges and tangled lignum could assist to speed up restoration.

- There is a requirement under the Victorian Water Act that Drainage Schemes are managed in an environmentally sound way.

- It appears that following a review of drainage schemes in Victoria that management of drainage schemes will fall more under the management of local government.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY

| The loss of wetlands has been dramatic with 90 -95% drained in the south-east of South Australia and over 60% drained in the Glenelg Hopkins region of Victoria. |

| Nature Glenelg Trust have have undertaken about 20 wetland restoration sites in south-west Victoria. |

| Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains are one of our Nationally listed communities and Critically endangered under the EPBC Act 1999. |

| The total area of intact Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands is much less than previously thought (only 563.12 ha from the predicted 7,296ha total in the listing). Most of these wetlands are less than 5 ha. |

| Corner Inlet contains a diverse range of habitats including fringing salt marshes, mud flats, deep channels, shallow seagrass beds, and barrier islands. |

| Corner Inlet Connections is a partnership project co-ordinated by the West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority. The inlet's proximity and dependence on a healthy catchment requires support from all people in the catchment to reduce nutrient inflow into the system. |

In terms of restoration, wetlands are highly adaptive ecosystems which depending on the circumstances can have a capacity for rapid restoration and recovery potential.

See the full list of previous video conferences