Video conference notes 5 February 2015 - Native fish

SWIFFT video conference notes are a summary of the video conference and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This video conference was supported through resources and technology provided by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria. SWIFFT wishes to thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations.

The first video conference for 2015 had a theme on Native Freshwater Fish.

A total of 95 participants were connected across 16 locations; Ballarat, Bairnsdale, Benalla, Bendigo, Colac, Geelong, Hamilton, Heywood, Horsham, Heidelberg (Arthur Rylah Institute), Melbourne (Nicholson Street), Mildura, Orbost, Traralgon, Warrnambool, Wodonga.

List of groups/organisations in attendance

Educational: Federation University Australia, Bendigo TAFE

Local Government: City of Bendigo, Bass Coast Shire.

Field Naturalist Clubs: Geelong, Hamilton, Portland.

Community Conservation Groups: Windamara Aboriginal Corp., Geelong Environment Council, Benalla Landcare, Bellarine Landcare.

Conservation Organisations: Nature Glenelg Trust, West Gippsland CMA, Glenelg Hopkins CMA, Wimmera CMA, Dept. of Environment, Land, Water and Planning staff across 14 locations, inc. Nicholson Street Melbourne and Arthur Rylah Institute, Heidelberg, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) - Fisheries, Birdlife Australia, Game Management Authority, Vic Forests, Native Fish Australia - Wimmera, Murray Darling Freshwater Research Centre.

Industry: Vic Roads, Biosis, Biodiversity Services.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY Quick take home messages from this video conference or read through the speaker summaries.

- Conservation of native fish in coastal wetalnds

- Conservation management of Victoria's Macquarie perch

- Conserving threatened small bodied freshwater fish – Murray Hardyhead

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

The conservation of native fish in coastal wetlands - Lauren Veale & Nick Whiterod, Nature Glenelg Trust

Lauren introduced the topic by explaining the areas of south-eastern South Australia and south-west Victoria once comprised a vast wetland complex. Since European settlement there has been extensive drainage, land clearance and conversion to agricultural production with about a 90% loss of wetlands in south-east South Australia and a 60% loss in south-west Victoria. Some of the remaining freshwater coastal wetlands and streams are biodiversity hot spots containing nationally listed fish species such as the Yarra Pygmy Perch, Variegated Pygmy Perch and the Glenelg Spiny Crayfish.

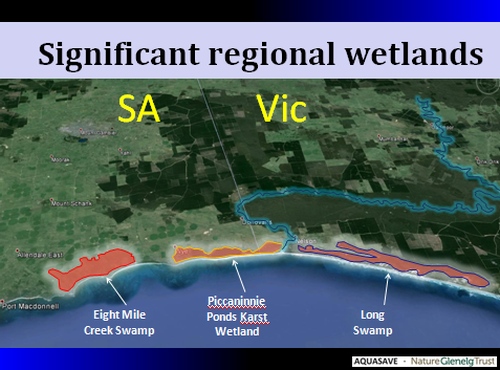

Regionally significant freshwater coastal wetlands on the Victorian - South Australian border

- Eight Mile Creek Swamp

- Piccaninnie Ponds karst Wetland

- Long Swamp

Lauren explained the term karst refers to streams and wetlands that are supplied from groundwater as it pushes up through the limestone.

Eight Mile Creek Swamp

The Eight Mike Creek complex is comprised of a series of large deep pools which contain rich aquatic plant life. The system is connected to the sea by streams which have suffered a significant loss of riparian vegetation.

Features of Eight Mile Creek swamp;

- Seven isolated rising-springs -the largest being Ewan's Ponds

- Sampled regularly since 2000

- 16 native species recorded in 2008

- Recent sampling focussed on change and abundance of Glenelg Spiny Crayfish and Variegated Pygmy Perch

The swamp is considered critically endangered habitat but there has been a decline in threatened species.

Threats include reduced groundwater flows, increased nutrients, decline in water quality and aquatic vegetation die off.

Due to the low sea level of the wetlands any long-term, sea level rise poses the greatest risk to the system.

Piccaninnie Ponds karst wetland

This wetland complex comprises three main areas; the main ponds, the eastern wetland and pick swamp to the west of the main ponds.

The area contains a number of rising springs with the main ponds having a depth up to 110 metres. The system is connected to the sea by two streams.

Pick swamp underwent major restoration in 2005 to reinstate water levels which significantly improved aquatic habitat.

The eastern wetland had restoration works carried out in 2013 to reinstate a levee holding water for the swamp which has resulted in a significant expansion of wetland habitat. Lauren spoke about the increased distribution and abundance of Southern Pygmy Perch and Common Galaxias in response to wetland enhancements and improved connectivity with the sea through connections with the Glenelg estuary.

Piccaninnie Ponds now supports a diversity of habitats and a diverse fish community with 17 fish species; two are nationally threatened (Dwarf Galaxias and Yarra Pygmy perch). There are no records of introduced species at this site. Yarra Pygmy Perch have only been found in one spring. Monitoring over the past five years has found a severe decline in Yarra Pygmy Perch to the point where it is considered close to extinction at this site.

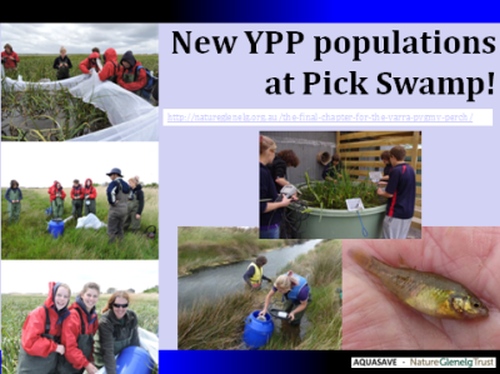

Yarra Pygmy Perch recovery project

A special translocation project has been established to reintroduce Yarra Pygmy Perch into Pick Swamp. This project involves captive breeding in an aquaculture facility and release through involvement of schools at Millicent High School and Kingston Community School.

Results from monitoring indicate the fish are progressing well at Pick Swamp which means the project has successfully established a new population at Piccaninnie Ponds.

Yarra pygmy perch release at Picks Swamp - 2014 from Lachlan Farrington on Vimeo.

More details project blog

Long Swamp

Lauren spoke about restoration works which involved blocking off drains which were created in the 1950's. This has enabled the water levels to rise, expand the swamp area and increase connectivity throughout the swamp. Baseline monitoring was conducted in 2014 with follow up surveys planned for 2015. Long Swamp supports a diverse range of fish species from freshwater to estuarine species.

See: Long Swamp restoration project - Nature Glenelg Trust

Summary

- Remnant freshwater habitats are critical to the persistence of threatened fish species.

- Restoration at key sites is having positive benefits.

- Some species (i.e. crayfish) are still declining.

- Collaborative work is occurring with success but more is needed.

Contact: Lauren Veale, Nature Glenelg Trust

Key points from questions

- It is thought that decline of Yarra Pygmy Perch at some sites could be through genetic deterioration from inbreeding.

- Reintroduced populations exhibit good levels of genetic diversity at levels similar to healthy wild populations.

- The need to consider any implications of onshore natural gas production on freshwater karst wetlands was raised.

- Trial sandbag structures have been used to fine tune wetland water levels.

- A scientific paper on the Piccaninnie Ponds restoration is planned for future publication.

Conservation management of Victoria's Macquarie perch : Sit and watch or learn and do? - Zeb Tonkin, Arthur Rylah Institute, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria

Zeb provided an overview of Macquarie Perch Macquaria australasica which is a medium sized freshwater fish (up to 465 mm) endemic to the Murray Darling Basin and a couple of populations on the eastern seaboard. It is a historically dominant species in the mid-upper reaches of streams north of the Great Dividing Range in Victoria and forms an important recreational fishery.

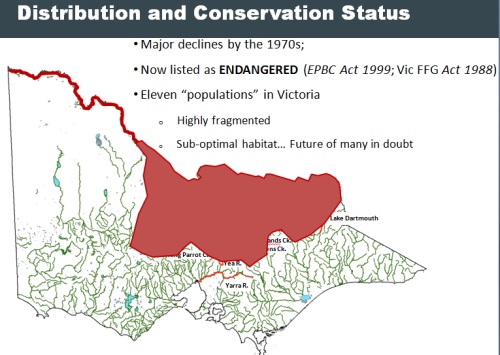

Distribution and status of Macquarie Perch

Listed as endangered under the EPBC Act 1999 and the Victorian FFG Act 1988.

There are eleven highly fragmented “populations” in Victoria with many populations in sub-optimal habitat which places their future in doubt.

Habitat

Macquarie Perch is primarily a riverine species but can establish populations in suitable lakes where fish undergo migrations to riverine habitats in Spring. Lake Eildon and Lake Dartmouth are important impoundments which have been the focus of research into this species.

Spawning habitat comprises pool / riffle sequences where eggs are deposited at the base pools and are washed into riffle areas where they lodge in the substrate.

Connectivity of habitat for migration of adults and dispersal of juveniles from spawning sites requires areas of habitat and refuge pools with adequate depth. Boulders, instream wood and an intact riparian zone of native vegetation are important.

Habitat to maintain productivity and recruitment strength requires natural flow regimes.

Ecology

Macquarie Perch is a long-lived species recorded up to 26 yrs of age (growing to 420 mm TL). Diet comprises aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates. It is a generalist schooling species which can form dense aggregations for several months during the spawning season. Peak spawning occurs in November when temperatures are above 16 °C. There are a number of known key spawning sites where dense aggregations occur. The King Parrot Creek and the Yarra River have been studied during the spawning season.

Macquarie Perch spawning aggregation video by Zeb Tonkin - ARI

Decline of Macquarie Perch

Construction of dams and weirs which act as a blockage to fish migration has been a major factor in this species decline. In addition, discharge from dams often results in cold water pollution which nullify spawning condition. Dams also prevent connectivity and dislocate populations above and below dams.

Heavy fishing pressure at aggregation sites meant Macquarie Perch were easily taken. Zeb referred to a quote from Cadwallader & Rogan 1977. “In 1959 and 1960, the Macquarie perch migration coincided with the opening of the angling season. The total catch from the Jamieson and Goulburn Rivers during the opening week of each season was estimated to be 2 – 3 ton of fish”

Threatening processes

Fragmented populations which now contain low numbers of fish are particularly vulnerable to threats e.g.

- Sedimentation - filling critical refuge pools and smothering spawning habitat and eggs.

- Catastrophic events - droughts, major floods, bushfires and associated runoff.

- Habitat Degradation - riparian health, desnagging and poor water quality.

- Exotic species interactions - redfin and carp, quantified impacts unknown.

Management actions

- Dredging sand from refuge pools.

- Resnaging and replanting riparian zones.

- Removal of exotic species removal (e.g. Sevens Ck).

- Restocking with hatchery bred fish where possible.

- Fisheries regulations and enforcement to protect spawning aggregations.

- Translocation responses to catastrophic events e.g. salvage from streams under sever environment stress and relocation back when conditions become more suitable. Zeb spoke about the temporary relocation and release of 35 fish from King Parrot Creek and 32 fish from Hughes Creek in March 2009 following drought and bushfires.

Conservation objectives

Objectives are focused on preservation of remaining populations, however it is highly likely that some marginal populations will crash particularly in light of climate change projections. Zeb emphasised it is very important to preserve as many of the current populations as possible while also undertaking long term solutions with objectives focussed on increasing population resilience through:

- Population expansion

- Population connectivity

- Ecosystem health

- Education

Goulburn Broken CMA Macquarie Perch Plan 2015

This plan recognises the highly fragmented populations of Macquarie Perch in the Goulburn - Broken Rivers system with a key objective of increasing the resilience of several populations by expanding populations downstream into Goulburn River and Lake Eildon through improving connectivity between Hughes Creek, King Parrot Creek and Yea River.

Catchment managers from the GBCMA, engineers, geomorphologists, hydrologists, ecologists and landholder / local community have worked together to investigate and formulate means of improving connectivity.

North East Victoria - Ovens River project

This project is aiming to create a new self-sustaining population of Macquarie Perch in the Ovens River. The Ovens River once supported an abundant population of Macquarie Perch which had become locally extinct. The project proceed on the basis that the river is large, unregulated with good connectivity and habitat. The project is also supported by the North East Catchment Management Authority works programs and has good levels of community support.

Zeb spoke about the Lake Dartmouth population which had been in decline. Monitoring since 2008 indicates the population has been reinvigorated as the lake has begun to fill. This presented a good opportunity to build a new population in the Ovens River.

The plan includes a minimum 5 years stockings and 2 year translocation (2013 – 2018)

- Fisheries Victoria hatchery production (10 000 – 40 000 fish / year)

- 2 years translocated fish from Lake Dartmouth (~300 juveniles/adults)

- The release of fish is planned and monitored through a reintroduction plan to safe-guards against collapse. The goal is to have >1000 adult females to reduce chance of population collapse.

Yarra River

Melbourne Water has been actively involved with improving overall river health and spawning conditions for Macquarie Perch through the use of environmental flow management. There is on-going monitoring and population modelling to provide optimum conditions for Macquarie Perch recruitment.

Conclusion

Long term restoration of habitat and population recovery is more preferable than short term short term band aid solutions.

The recovery of Macquarie Perch is difficult with a long road to recovery - a sustained effort by water and resource managers together with community support is needed.

Education is vital to achieve short and long term objectives.

Key points from questions

- Interactions between Brown Trout and Macquarie Perch are thought to be an issue when Macquarie Perch populations are depleted and on the brink of extinction but there are cases where Trout an Macquarie Perch co-exist.

- Reintroductions of Macquarie Perch are targeted to stretches of streams that provide more favourable habitat for Macquarie Perch than trout e.g. avoid releases into headwater areas which favour trout.

- Redfin and Carp are considered to pose more competition and habitat destruction risk than trout.

- Catch and release angling is not a major issue but angling disturbance in spawning areas is a concern.

- Recreational fishing; The taking of Macquarie perch is prohibited in all Victorian waters except Lake Dartmouth, the Yarra River and the Upper Coliban Reservoir (and their tributaries). In these waters there is a closed season from 1 Oct-31 Dec inclusive. The legal minimum length is 35 cm; Bag limits Lake Dartmouth (and its tributaries): 1; Yarra River (and its tributaries): 2 ; - Upper Coliban Reservoir (and its tributaries): 2; All other Victorian waters: 0 Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide

- Outside Victoria other populations are thought to be in a worse state than Victoria, populations exist in the Murrumbidgee River, ACT, Cataract Dam, and headwater of Shoalhaven River.

- There are no records from the Wannon River since the early 1980's. This was a stocked population many years ago.

- Macquarie Perch have been recorded migrating distances up to 60km from lakes to spawning areas. Adult non - spawning fish don't move far. Barriers can have a major impact on reaching spawning areas.

- The Yarra River population was established in the 1920's primarily from the Goulburn River with some Mitta Mitta river stock.

- Further introductions outside the natural range are limited mainly due to production of stock which is a difficult process for this species. Reintroduction efforts need to be directed to their natural range as a priority.

Contact: Zeb Tonkin, DELWP, Arthur Rylah Institute

Conserving threatened small bodied freshwater fish – Murray Hardyhead as a case study. Iain Ellis, Murray Darling Freshwater Research Centre

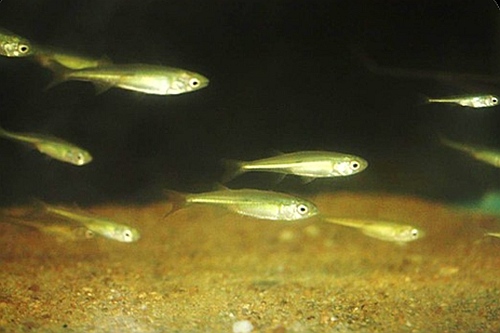

Murray Hardyhead Craterocephalus fluviatilis are a small silvery fish growing to about 8cm. They tend to form schools are often referred to as minnows along with other small bodies species. They can be sometimes confused with the Unspecked Hardyhead which is similar in appearance and more common.

Conservation status

The Murray Hardyhead is listed as Endangered under the EPBC Act 1999 and Listed as threatened under the Victorian Flora & Fauna Guarantee Act 1988. The Australian Society for Fish Biology considers Murray hardyhead to be Critically Endangered. Internationally they are considered endangered under the IUCN.

Iain said the species has suffered a severe decline in recent years. In 2000 there were approximately 17 populations by 2014 only 5 populations remained. This decline was attributed to the drought and there are grave concerns for the species when the next drought occurs.

Habitat

Historically, Murray Hardyhead would have been a flood dispersing species where they would have survived on the fringes of the flood plain in isolated wetland systems that became salty. During a flood these systems would have reconnected allowing dispersal.

Most records come from salty lakes, irrigation basins, creeks, rivers and drainage channels with salinity up to 110,000EC in areas containing submerged vegetation e.g. Ruppia Sea tassel . The Murray Hardyhead has not been recorded from the main part of the Murray River for a long time.

Distribution

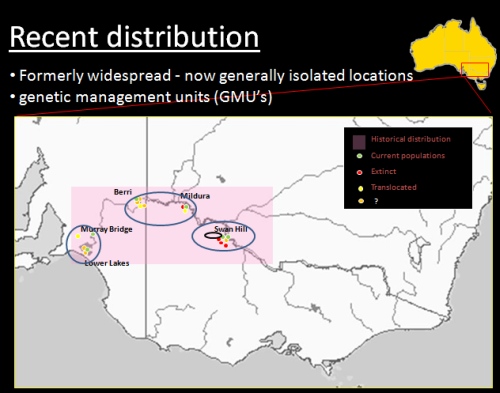

Iain said the Murray Hardyhead is distributed in the Murray, Darling and Murrumbidgee rivers with the main stronghold being sections of the Murray River from Kerang to Swan Hill and down the Murray to the lower lakes. The species has not been recorded very far up the Darling River (if at all) and not far up the Murrumbidgee with no recent verified records. Populations in the Murray have become isolated with four genetically distinct management units.

Threats

Iain spoke about a number of threats which become interrelated and basically revolve around changes to natural river flows. Lack of regular flows with sufficient enough volume to reconnect fringing wetlands on the Murray floodplain with the main river is a major problem, this impacts on availability of habitat, connectivity and reproduction. Weirs are barriers which impeed dispersal, they can also permanently alter fringing wetlands upstream of the weir by reducing salinity which favours introduced species which are normally excluded in more saline wetlands. In these environments introduced species such as carp, redfin and mosquito fish Gambusia can easily out compete the Murray Hardyhead.

Research

Iain said he has been studying the Murray Hardyhead since 2004, he is also aware of some earlier work by ARI in the Kerang area. There is also some monitoring being conducted in the lower Murray lakes by Nick Whiterod.

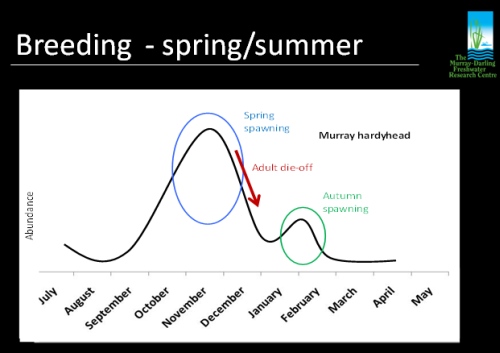

Murray Hardyhead are a short lived species less than two years old. They are regarded as an annual species which needs to reproduce each year for the population to persist.

Breeding takes place during Spring/Summer, eggs are sticky and deposited on aquatic vegetation such as Rupia, peak hatching takes place in November. After spawning during December and January many of the adults die off and the population declines. When conditions are ideal there can be a second Autumn spawning from the previous November spawning.

Diet comprises Zooplankton and micro-invertebrates e.g. midge larvae, mosquito larvae.

Conservation management

There is a current recovery plan for Murray Hardyhead which has been recently revised and is in the approvals process. The plan is essentially aimed at improving the status of Murray Hardyhead by preserving the known populations and increasing its areas of occupancy.

The recovery plan does not guarantee funding for the necessary actions and because the Murray Hardyhead is such a short lived species there is a high risk of dramatic population decline occurring while implementation of the recovery process is being sorted out.

Key conservation tools

- Environmental watering to maintain priority populations in identified wetlands whilst ensuring high enough salinity levels are maintained.

- Captive maintenance of rescued fish from populations at imminent risk.

- Captive breeding (can be expensive and difficult).

- Translocation to suitable habitats to reduce the risk of catastrophic loss.

- Translocation to surrogate dams which have been prepared and managed to support Murray Hardyhead. This also provides a source of fish for re-stocking to natural habitats and is more cost effective than captive management in tanks.

- Monitoring of status/threats of primary and secondary populations.

Impediments

Iain spoke about the difficulties of managing Murray Hardyhead populations which have multiple management agencies. Confusion over who is responsible and the approvals process can be long meanwhile the population can be gone.

A post drought 'dis-urgency' has emerged as an issue where people are not mindful of the ongoing threats to the Murray Hardyhead, whereas during the drought more attention was given to maintaining key wetlands.

The recovery of Murray Hardyhead is aimed at getting this species off the threatened list, however even though the drought has passed and there has been more water about the species is still in rapid decline.

Conclusion

Iain said we need to be pro-active by looking at recovery across the range of the fish to improve natural dispersal rather than just keeping a few pockets of fish alive until the next drought when there will be a high chance of losing them.

Iain acknowledged relevant organisations and the dedication of people who have worked and volunteered their time towards conservation of the Murray Hardyhead.

Contact: Iain Ellis www.mdfrc.org.au

Murray Hardyhead - Craterocephalus fluviatilis Image: MDFRC

Key points from questions

- Translocation requires a case by case investigation to ensure conditions are suitable and that there are not introduced species that will eat any released fish. Translocation outside the natural range would normally not proceed.

- Turbidity is often reduced in saline waters which allows growth of suitable aquatic vegetation.

- The main difference in habitat between the Unspecked Hardyhead, other Hardheads and the Murray Hardyhead is that the Murray Hardyhead is more adapted to survive in higher salinity waters around 15000 EC.

- The natural Murray flows were once low flowing with periodic floods which filled areas which naturally became salty (favouring the Murray Hardyhead), these habitats have changed forcing the Murray Hardyhead to compete in less suitable habitats.

General discussion summary

- A decline in the Glenelg Spiny Cray population in the coastal karst ponds is thought to be cause by reduced groundwater flows. This species is reliant on fast flowing environments. It is noted that where outlet streams have been modified the flows are now greater and this is where the Glenelg Spiny Cray's are doing best.

- Fish populations that survive in isolated habitats have an increased probability of decline due to lack of genetic diversity.

- ARI is involved in a number of freshwater fish projects. See ARI site

KEY POINTS SUMMARY

| Remnant freshwater habitats on the Victorian and South Australian border are critical to the persistence of threatened fish species such as Yarra Pygmy Perch, Variegated Pygmy Perch and the Glenelg Spiny Crayfish. |

| There are only eleven highly fragmented populations of the endangered Macquarie Perch in Victoria with many populations in sub-optimal habitat which places their future in doubt. |

| The recovery of Macquarie Perch is difficult with a long road to recovery - a sustained effort by water and resource managers together with community support is needed. |

| Murray Hardyhead are a flood dispersing species which survive on the fringes of the Murray River flood plain in isolated wetland systems that become salty. |

| The Australian Society for Fish Biology considers Murray Hardyhead to be Critically Endangered. In 2014 only five isolated populations remain in wetlands along the Murray River. |

| The Murray Hardyhead is a short lived species and there is a high risk of dramatic population decline or possible extinction if urgent conservation measures are not implemented. |

See the full list of previous video conferences

Agenda for the next SWIFFT video conference