Diamond Firetail

Diamond FiretailStagonopleura guttata | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Estrildidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Vulnerable (IUCN 2021) |

| Australia: | Vulnerable (EPBC Act) |

| Victoria: | Vulnerable (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| FFG: | List; no Action Statement |

The Diamond Firetail is one in a group of five Australian finches often referred to as firetails because of their distinctive red rump and red upper tail coverts. Diamond Firetails are found from Queensland, through New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and eastern South Australia to the Eyre Peninsula where they mostly occur on the inland side of the Great Dividing Range.

There are three species of 'firetails' which occur in Victoria;

- Diamond Firetail (Stagonopleura guttata - south-eastern Australia including Victoria),

- Beautiful Firetail (Stagonopleura bella - south-eastern Australia including Victoria),

- Red-browed Finch Firetail (Neochmia temporalis - south-eastern Australia including Victoria).

Other firetails include Red-eared Firetail (Stagonopleura oculata - Western Australia) and Painted Finch Firetail (Emblema pictum - western-central Australia).

The Diamond Firetail is grey to buff-brown above and white underneath, it has a bright crimson rump and upper-tail coverts. Adult males have a grey head, red bill and black around the eye (lores). The throat is white and a distinctive black band extends across the chest and down the flanks with prominent white spots on the flanks. Adult females are similar to males except that the breast-band and flank markings are is less discernable, the lores are a brownish black and the bill is not red. Immature birds have a black bill and the bright crimson rump and upper-tail coverts of adults but more of an olive-brown appearance on back and wings, with bars of greyish-white on the flanks.

Diamond Firetail (juvenile). Image courtesy: David Whelan, 2021 wildpix.com.au

Distribution

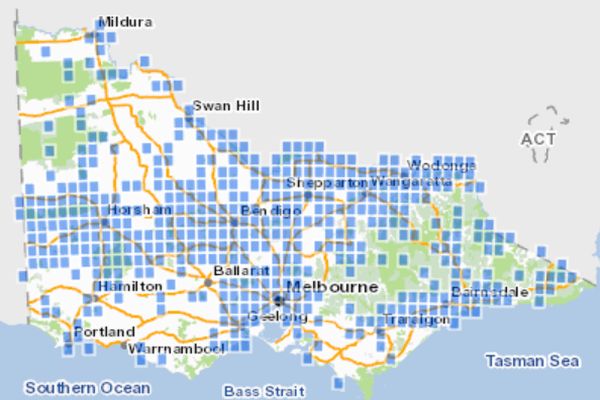

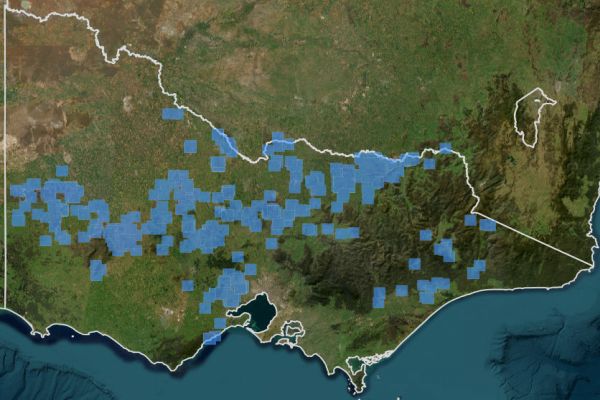

In Victoria, the Diamond Firetail is most frequently found in the Goldfields and Victoria Riverina bioregions. Other key bioregions include; Inland Slopes, Wimmera, Central Victorian Uplands, Lowan Mallee, Volcanic Plains, Murray Fans, Greater Grampians and South East Coastal Plain.

Key Local Government Areas for Diamond Firetail

(in order of importance > 300 records) Source: (ALA 2016)

- Loddon Shire

- Greater Bendigo City

- Hindmarsh Shire

- Horsham Rural City

- Greater Geelong City

- Indigo Shire

- Wangaratta Rural City

- Benalla Rural City

- Central Goldfields Shire

- Moira Shire

Ecology & Habitat

The Diamond Firetail is regarded as being mainly sedentary across many areas of Victoria and often occur in small flocks. In Victoria, they occur between 300-700mm rainfall in lowlands and foothills and mainly inhabit grassy woodlands or wooded farmlands containing River Red Gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Yellow Gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon, Murray Pine Callitris gracilis or Buloke Allocoasuarina luehmannii near permanent water but is less reliant on permanent water than the other two species in its genus (Immlemann 1982, Emison et al. 1987).

In East Gippsland, there are observations of small flocks which move around areas like the Buchan, Ensay and Suggan Buggan farming valleys.

Nest description

Diamond Firetails usually nest within 4.5m of the ground, although some nests have been recorded at heights above 20m (Cooney et al. 2005). Nests are built in thickly foliaged branches of trees and shrubs, or in mistletoe growing on eucalypts. Nests up to 30 cm in diameter are built with green flexible plant material. They have a spherical or bottle shaped nesting chamber and variable entrance tunnel up to 15 cm long. Breeding nests are lined with great amounts of very fine grasses and white feathers (Immlemann 1982).

Diamond Firetails are known to weave flowers into the entrance of their nests. McGuire and Kleindorfer (2007) conducted a study in the Mount Lofty Ranges to determine the occurrence of flowers and whether nests with flowers were more successful than nest without flowers. They found that 70% of nests studied had flowers woven into the entrance; however predation occurred irrespective of the number of flowers found on nests. They also suggest that Diamond Firetails prefer long stems in building nests, due to its structural stability and being easier to weave, and the presence of flowers is a by-product of the preference of suitable nest-building material.

Cooney et al. (2005) found that Diamond Firetail’s nests are built in mistletoe far more often than would be expected by chance, where the reasons for this include enhanced levels of concealment in mistletoe which may reduce the risk of predation and mistletoe is a good structure for nest building that provides a favourable microclimate for incubation.

Breeding

Diamond Firetails are thought to mate for life. They breed between August and January, with a clutch of 4-9 pale white eggs, 18 by 33mm. Incubation is 12-15 days which starts after the second egg has been laid. Both sexes share in incubation and care of the nestlings, and young leave the nest when they are 24-25 days old. Juvenile moult starts soon after young have left the nest and is completed when they are about 12 weeks of age (Immlemann 1982; Read 1987).

Feeding

Diamond Firetails are ground-feeders that predominantly eat ripe and half-ripe seeds of various grasses but are also known to feed on seeds of herbs, bushes and trees as well as insects and worms (Immlemann 1982; Read 1987). A study conducted by Read (1994) in the Mount Lofty Ranges of South Australia looked at the diet of Diamond Firetails by analysing seeds sampled from the crops of wild-caught birds. He found that grasses are an important part of Diamond Firetail’s diet, where 73.3% of crops sampled contained grass seeds, and was the dominant seed type in 65.1% of crops with no arthropods being found. It appeared as though Diamond Firetails concentrated on weed and pasture grasses rather than native species, as introduced plants often produce abundant seeds. Read (1994) also considers that although the diet of Diamond Firetails has changed significantly in recent times, the loss or reduction of food plants does not appear to explain their decline.

Threats

Habitat loss

The Diamond Firetail has declined over its entire range over the past 30 years due to the loss, fragmentation and degradation of habitat (Myers 1987). Much of the Diamond Firetail’s habitat has been cleared and what remains is highly fragmented and degraded due to the increase in edge effects, grazing by domestic stock and rabbits, and the removal of firewood (Garnett and Crowley 2000). The remaining Diamond Firetail populations are small and isolated, and have no means of breeding with other populations, which has already resulted in the local extinction of some populations in Victoria (SAC 2000).

Predation by Currawongs

With increased fragmentation of habitat there has been an increase in edge effects which includes the increase of edge-specialists. The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (2005) found that nest predation of Diamond Firetails by Pied Currawongs has increased with the degradation of fragmented remnants. Weeds species with berries, such as Hawthorn and Cotoneaster, can invade remnants which has assisted an increase in the population of Pied Currawongs.

Loss of woodland birds

There is currently a trend in the decline of woodland birds across Australia, where at least one in five woodland birds is threatened or declining (Olsen et al. 2005). In Victoria, only 32% of eucalypt woodlands and 5% of eucalypt open woodlands remain, and these are poorly represented in reserves and highly fragmented (Commonwealth of Australia 2001).

Case Study at Inverleigh in Victoria

Conole (2002) has recorded the local extinction and decline of birds in a woodland remnant at Inverleigh over a 20 year period. Thirteen bird species have become locally extinct and a further nine (including the Diamond Firetail) have become rarer and may become locally extinct in the future. Bird species at Inverleigh have declined or become locally extinct at Inverleigh due to:

- removal of standing and fallen timber for firewood, which removes a gleaning substrate for some bird species

- reduction in shrub diversity, which reduces food and nesting sites

- proliferation of Kangaroo Thorn (Acacia paradoxa) and exotic grasses, which does not provide adequate diversity and quantity of prey for a full community of insectivorous birds

- reduction in invertebrate diversity as a result of overgrazing by kangaroos and rabbits

- reduction in connectivity of habitat in the landscape

(Source: Conole 2002)

Retaining remnant vegetation

It has been found that farms with high value remnant native vegetation are important for supporting declining or vulnerable species of farmland birds. A study by Cunningham et al. (2008) found that remnant native vegetation was more important than tree planting, in a approx. 3:1 ratio. It was found that loss of remnant native vegetation and associated habitat qualities may not necessarily be offset by revegetation in the short to medium term, particularly for species such as Diamond Firetail, Hooded Robin, Jacky Winter, and Crested Shrike-Tit might.

It is suggested that farm management for improved bird conservation should account for the cumulative and complementary contributions of many components of remnant native-vegetation cover (e.g., scattered paddock trees and fallen timber) as well as areas of restored native vegetation (Cunningham et al. (2008).

Conservation & Management

The conservation status of Diamond Firetail was re-assessed from Near Threatened in 2013 (DSE 2013) to Vulnerable in 2020 as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria (DELWP 2020). This species is now listed as Vulnerable in Victoria and under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024.

Suggested Actions

Survey, map and rank in priority Diamond Firetail populations and habitats in Victoria.

Conserve habitat on private land by using appropriate incentives, to promote sound management of remnants, encourage greater connectivity between sub-populations, and reduce heavy grazing by stock in areas known or potential habitat to enable flowering and seeding of grasses and forbs required by Diamond Firetails (Garnett and Crowley 2000).

Manage public land adequately for the conservation of Diamond Firetail populations by placing Diamond Firetail sub-populations on public land under secure conservation management, especially in timber reserves, transport corridors and local government land (Garnett and Crowley 2000).

Research Diamond Firetail habitat and resource requirements, characteristics of biology that make species susceptible to fragmentation, and other threats to populations such as predation.

Undertake long-term monitoring of remnant sub-populations to assess species conservation status and to identify key breeding and foraging habitat (Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 2005).

Educate the community about the significance of woodland birds and provide measures that can be taken to conserve these species.

Projects & Partnerships

Birdlife Australia conducts the Woodland Birds for Biodiversity project which incorporates Diamond Firetail.

References & Links

- ALA (2016) Atlas of Living Australia, Diamond Firetail. Accessed 26 May 2016.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2001) Major vegetation groups and their status in each State and Territory: Victoria, National Land and Water Resources Audit, accessed 24 September 2007 from http://www.anra.gov.au/

- Conole, L.E. (2002) Local extinction and decline of birds in a woodland remnant at Inverleigh, Victoria. Corella, Vol.26, pp.41-46.

- Cooney, S.J.N. and Watson, D.M. (2005) Diamond Firetails (Stagonopleura guttata) preferentially nest in mistletoe. Emu, Vol.105, pp.317-322.

- Cunningham R.B., Lindenmayer D.B., Crane M., Michael D., MacGregor C., Montague-Drake R., Fischer J. (2008) The Combined Effects of Remnant Vegetation and Tree Planting on Farmland Birds http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00924.x

- Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (2005) Diamond Firetail – profile, http://www.threatenedspecies.environment.nsw.gov.au/tsprofile/profile.aspx?id=10768

- DELWP (2020) Provisional re-assessments of taxa as part of the Conservation Status Assessment Project – Victoria 2020, Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Victoria.

-

DSE (2013) Advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria - 2013, Department of Sustainability & Environment, East Melbourne, Victoria. (now Department of Environmant, Land, Water and Planning).

- EPBC Act (2025) Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) https://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicthreatenedlist.pl#birds_vulnerable

- Emison, W.B., Beardsell, C.M., Norman, F.I. and Loyn, R.H. (1987) Atlas of Victorian Birds. Department of Conservation, Forests and Lands and the Royal Australian Ornithologists Union, Melbourne.

- FFG threatened list (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - June 2024, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria.

- Garnett, S.T. and Crowley, G.B.( 2000) The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000. Birds Australia/Environment Australia, Canberra.

- Immlemann, K. (1982) Australian Finches in Bush and Aviary. Angus and Robertson Publishers, Australia.

- IUCN (2021) BirdLife International. 2022. Stagonopleura guttata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T22719660A211542365. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T22719660A211542365.en. Accessed on 07 February 2025.

- McGuire, A. and Kleindorfer, S.( 2007) Nesting success and apparent nest-adornment in Diamond Firetails (Stagonopleura guttata). Emu, Vol.107, pp.44-51. http://www.publish.csiro.au/?paper=MU06031

- Myers, D. (1987) The Firetails-A Summary of Current Data. Australian Aviculuralist, Vol.7, pp.165-175.

- Olsen, P., Weston, M., Tzaros, C. and Silcocks, A. (2005) The State of Australia’s Birds 2005. Birds Australia, Victoria.

- Read, J. (1987) The Ecology of Firetail Finches in Southern Australia. Thesis, University of Adelaide.

- Read, J.L. (1994) The Diet of Three Species of Firetail Finches in Temperate South Australia. Emu, Vol.94, pp.1-8. http://www.publish.csiro.au/?paper=MU9940001

- SAC (2000) Recommendation on a nomination for listing; Diamond Firetail Stagonopleura guttata (Nomination No. 488), Scientific Advisory Committee, Flora & Fauna Guarantee, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne.

- VVB (2025) Visualising Victoria's Biodiversity map portal.

More Information

Please contribute information regarding Diamond Firetail in Victoria - observations, images or projects. Contact SWIFFT