Grey-headed Flying-fox

Grey-headed Flying-foxPteropus poliocephalus | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Eutheria |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Vulnerable (IUCN 2008) |

| Australia: | Vulnerable (EPBC Act 1999) |

| Queensland: | Least concern |

| New South Wales: | Vulnerable |

| Victoria: | Vulnerable (DEECA 2023) |

| FFG: | Listed (FFG 2016) |

.jpg)

The Grey-headed Flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus also referred to as the Grey-headed Fruit-bat is endemic to the forests of south-eastern Australia and is found from mid Queensland to southern Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales.

The name flying fox is derived from the shape of their face but they are not related to foxes in any way and are not vermin. They are a native species, listed as vulnerable, have a diet of fruits and nectar and are beneficial to the environment.

The Grey-headed Flying-fox occupies at least two permanent camps in Victoria and seasonally disperses across parts of the state forming roosting camps from which it travels to feed on a variety of fruits, nectar and pollen from plants and trees in areas of native vegetation and also cultivated vegetation in back yards and parks.

The Grey-headed Flying-fox is the largest member of its family, weighing up to 1kg (600-1000g), with a wing span up to 1metre. They have a reddish-yellow mantle that completely encircles the neck, with a grey or white-grey head, and dark brown shaggy fur which extends to the ankle (Strahan 1995).

There are eight species of fruit-bat in Australia, but the only other species found in Victoria is the Little Red Flying-fox Pteropus scapulatus. The Little Red Flying-fox is a close relative of Grey-headed Flying-fox but more reddish brown all over without the grey face of the Grey-headed Flying-fox.

Another distinguishing feature of the Grey-headed Flying-fox is that it has fur down the full length of its leg whereas the Little Red Flying-fox only has fur extending to the knee. The Little Red Flying-fox also tends to have a more northern distribution when in Victoria.

In 2015, the National Grey-headed Flying-fox population was estimated to be 680,000 (±164,500). The population was thought to be relatively stable but may have declined between 2005 - 2012 (Westcott et al. 2015). More recent surveys between 2012 to 2022 found an average of 580,000 with total numbers ranging between 330,000 and 990,000, with strong seasonal variation (Vanderduys et al. 2024).

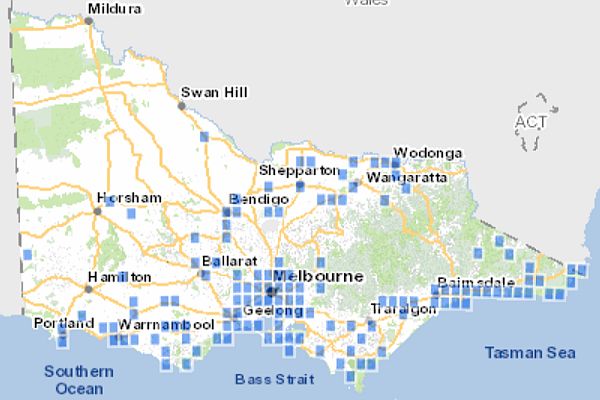

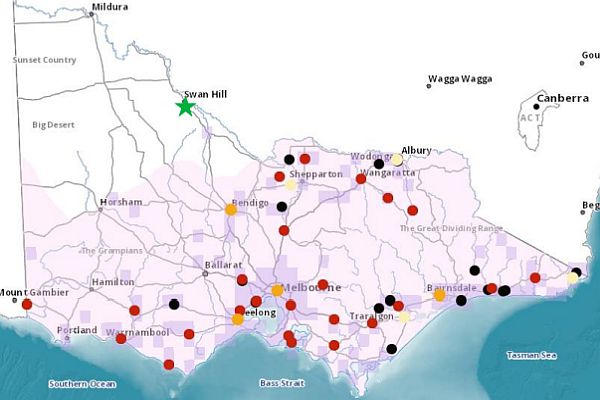

Distribution

In 2017 there were at least 11 Grey-headed Flying-fox roosting areas or camps in Victoria, 8 of these being in East Gippsland but by 2024 the number of camps had grown to at leat 24 being widespread across southern and norh-eastern Victoria.

Most Victorian records are concentrated between March-June but may extend from September to July (Menkhorst 1995; Van der Ree et al. 2006).

East Gippsland

Bairnsdale outskirts - usually occupied between December - May. Some use recorded prior to 2001 but counts of 5,000 each summer 2001-2009. Highest count 10,000 in January 2012. Counts conducted each month during this period.

Cabbage Tree Creek Fauna Reserve

- Palm Track site was occupied in 2003 by several thousand individuals but no further occupation up to 2008.

- Swan Track site has been used in a number of years by approx. 10,000.

Cann River - Site not used since 2002

Dowell Creek - Predominantly used in late-summer to autumn, used by large numbers in some years.

Karbethong - Numbers fluctuate, mainly used late summer - autumn. In 2003 approx 90,000 individuals, used by smaller numbers in 2005 and 2007.

Newmerella - Used in 2002 by up to 10,000 individuals then not recorded there until 2008.

Other areas of Victoria

Upper Maffra - in Wellington Shire. Used in 2004 by 5000 - 10,000 individuals when ironbarks were in flower.

Yarra Bend (moved from Melbourne's Royal Botanic Gardens in 2003) which had been established since 1986 is the second largest camp in Victoria> It has year round occupation and birthing.

Yarra Bend is the main camp location in Melbourne with numbers ranging from 30,000 to 50,000 during January to May 2010. Recent were: August 2015 (9,500), November 2015 (14,791), February 2016 (15,300) and May 2016 (7,050).

Geelong, Eastern Park - This Flying-fox camp became established in 2003 and has year round occupation and birthing during October. It is the most southern range of a breeding population in Australia. Peak numbers at Geelong occur from January to April where a maximum of about 18,000 have been recorded but generally the summer population has been around 5,000 individuals with a reduced winter population (Braverstock pers. com.).

Merrimu, Moorabool Shire - further monitoring of camp required.

Bacchus Marsh - Lerderderg River, camp in Willows noted 2019.

Bendigo, Rosalind Park - Flying-foxes present in winter months but numbers fluctuate from several thousand to the highest count 32,000 in June 2010. Reported that numbers significantly down in 2014/15.

Colac, Botanic Gardens - Significant increase since 2016/17, 2017/18 and 2018/19 with at least 4,000 individuals.

Warrnambool, Botanic Gardens - Numbers fluctuate around 2,500 but up to 10,000 have been recorded, yet in some years the population drops down to less than 500.

Ecology & Habitat

The Grey-headed Flying-fox is typically found near a permanent water source and exist in a range of habitats, including riparian forest, mangroves, urban, or suburban areas (Nelson 1965; Lunney & Moon 1997; Hall 2002). Camps are often in gullies, near water, and in habitats with a dense tree cover and are likely to be found in parks (McDonald-Madden et al. 2005).

Movement

The Grey-headed Flying-fox is a partial migrant, using winds to facilitate long distance movements, with round trips reaching up to 2000km (Tidemann & Nelson 2004). Large scale movements across the range are driven by a lack of resources and populations will migrate with response to the flowering and fruiting of food plants (Eby 1991). Breeding studies also show movements of 250 km over 15 months, with the furthest being 978 km in 5 months (Webb & Tidemann 1996).

.jpg)

Feeding

The Grey-headed Flying-fox is nocturnal, usually travelling 5-15 km to forage, although they are able to travel for distances up to 50km from their roost site (Tidemann & Nelson 2004; Spencer et al. 1991). They feed on nectar and pollen of native species in the families Myrtaceae and Proteaceae which are also sometimes supplemented with leaves (Parry-Jones & Augee 1991; Eby, 1991). They will also feed on fruit from introduced trees, cultivated fruit trees and fruit from native species such as the Lilly-pilly.

There is now a constant and reliable source of food for flying-foxes in Melbourne with 13 species of trees known to be in the diet of flying foxes indigenous to Melbourne, plus 87 species planted along streets and 45 species in backyards all adding to the diet availability. Flying-foxes feed on about 90% of the street tree species which are planted. There is also secure year round water from watering in parks and gardens (SWIFFT video conference Oct 2012) .

Breeding

The peak mating season runs from March to April with large aggregations being formed. These aggregations comprise individuals from a number of groups which results in a high degree of gene flow between colonies, suggesting one massive interbreeding population (Eby 1991; Spencer et al. 1991; Webb & Tidemann 1996). Individuals are identified using sight and smell (Hall & Richards 2000). Vocal communication is highly sophisticated, with over 20 situation-specific calls used (Strahan 1995).

Most births occur in October; young are carried on the ventral surface of foraging mothers for 4-5 weeks after birth, and then left in the camp at night to be suckled on the mothers return (Strahan 1995).

Population Status

In 2015, the National Grey-headed Flying-fox population was estimated to be 680,000 (±164,500). The population was thought to be relatively stable but may have declined between 2005 - 2012 (Westcott et al. 2015). More recent surveys between 2012 to 2022 found an average of 580,000 with total numbers ranging between 330,000 and 990,000, with strong seasonal variation (Vanderduys et al. 2024).

There were a few records of the Grey-headed Flying-fox in Victoria between 1884 to 1986 but in 1986 there was a very significant increase in numbers with about 100 animals setting up camp in Melbourne which has now turned into an established year round population. The heating up of Melbourne’s environment due to more concrete and bricks may have created a heat island effect which has favoured the establishment of this sub-tropical species in Melbourne (SWIFFT video conference Oct 2012).

Declines in Grey-headed Flying-foxes have occurred since the 1920’s (Ratcliffe 1931) and are linked to clearing for agriculture (Richards & Hall 1998). There has been a reported loss of 35% in the 1992 -2002 decade (Martin & McIlwee 2002). Loss of native vegetation through land clearing and logging across its range and increased human habitation has increased pressure on this species to forage in cultivated landscapes with orchards, parks and domestic fruit trees. The occasional "clash" between this species and humans is often due to starvation. Non-flowering of native species due to drought or loss of nectar can further exacerbate the situation (Richards & Hall 1998).

Outside of Victoria the culling of animals in orchards is a contributing factor to the decline of populations. At least 240,000 individuals could have been culled between Sydney and Queensland from 1986-1992 (Wahl 1994). Young will often starve under these circumstances if the mother is shot and doesn’t return to suckle the young at the roost site (Strahan 1995). In 2003-2004, the Australian Government ruled that in any of the participating states, shooting of Flying-foxes on orchards may occur, but only in accordance with the guidelines for the permits or licenses necessary (DEH 2003). This ruled that the total number killed in the 2003-2004 season would not exceed 1.5% of the lowest agreed national population estimate for the species (DEH 2003). This was deemed to be an acceptable culling level that would not jeopardize the recovery of the species. This figure undergoes review on an annual basis in order to maintain populations at a sustainable level (DEH 2003).

The Grey-headed Flying-fox is protected from culling in Victoria, although destruction permits may be issued for individual cases.

The population shift from its natural range to highly urbanized areas has often been mistaken as an expansion in population (Eby & Lunney 2002), but urban populations are subject to higher mortality through interaction with humans and human-related objects, such as power lines (Divljan et al. 2006).

Heat stress on young Flying-foxes has proven to be a threat with many hundreds of mortalities occurring in Victoria during heat wave conditions experienced during the 2008/09 summer. In the summer of 2019/20, it is estimated that around 5,000 flying-foxes perished in Victoria from extreme heat.

DEECA is the lead control agency for responding to wildlife welfare issues under The Victorian Response Plan for heat stress

Conservation & Management

- Monitoring of known roosting camps across Victoria.

- Undertake quarterly counts to estimate population size at Yarra Bend, as part of quarterly national census

- Control of access where required to prevent human disturbance

- Provide information to the public on the Grey-headed Flying-fox

- Prepare a Flora Fauna Guarantee Action Statement

- Develop a recovery plan

- Encourage research to improve understanding of key biological functions

Yarra Bend Park Flying-fox Campsite

There is active management of the Yarra Bend colony which has a designated 26-hectare Grey-headed Flying-fox Management Area. A Management Plan for the Yarra Bend Park Flying-fox Campsite was prepared in 2005 (DSE 2005).

Monitoring of the Melbourne Flying-fox colony occurs on a regular basis and is directed by the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology (ARCUE). Static counts of Flying-fox numbers at the roost site are conducted each fortnight, and flyout counts once per month (Van der Ree, pers. comm.; Davidson, pers. comm.). The number of young emerging at the roost site of the colony is counted every 10 days during the breeding season and the number of dead flying foxes occurring throughout the region are also taken sporadically over winter, and every 10-14 days during summer (Van der Ree, pers. comm.).

A review of the Yarra Bend Campsite was undertaken in 2009 to look at scientific research associated with delivery of the Management Plan (ARCUE 2009)

Research & management

National Recovery Plan for the Grey-headed Flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus was released in 2021.

A standard monitoring techniques for Grey-headed Flying-fox has been developed and used by each Flying-fox camp manager.

Liaison with interstate staff undertaking the National counts is undertaken so that they can let the Victorian monitors know when Grey-headed Flying -foxes are migrating into Victoria.

The Nature Conservation Council of New South Wales has a Flying-foxes Policy to assist conservation of Flying-foxes through identification and protection of important flying-fox habitat, better public education, and implementation of management measures (NCC 2010)

The National Flying-fox monitoring viewer provides information on the location of current camps.

Community participation

Most of the effort is focused on the Yarra Bend colony;

- Friends of Bats & Bushcare Inc. (A Parks Victoria Friends-of Group) activity support the Yarra Bend colony and carries out Victoria’s only annual Spring and Autumn soft-release for up to five hundred orphan and injured flying fox pups and adults each year. The group also undertakes community education. The Yarra Bend Park flying foxes enjoy an estimated 200,000+ visits per year from the community and are a favourite of international visitors. In Spring 2024 the area contained 1200 flying-foxes.

- Friends of Bats (Melbourne Field Naturalists Club of Victoria) are involved in a large range of activities with the Yarra Bend Park site.

References & Links

- ARCUE (2009) Yarra Bend Park Flying-fox Campsite: Review of the Scientific Research Prepared for the Department of Sustainability and Environment by: Rodney van der Ree, Caroline Wilson and Vural Yazgin Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology, 2009

- DEECA (2023) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - September 2022 Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria

- DSE (2005) Flying-Fox Campsite Management Plan Yarra Bend, Department of Sustainability & Environment, Victoria.

- DECCW (2009) Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW. July 2009. Draft National Recovery Plan for the Grey-headed Flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus. Prepared by Dr Peggy Eby. Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW, Sydney.

- EPBC Act (1999) Advice to the Minister for the Environment and Heritage from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC) on Amendments to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

- Date: September 2001 Advice re; Pteropus poliocephalus.

- DEH (2003) EPBC Act Administrative guidelines on significance – supplement for the grey-headed flying-fox, What you need to know about the grey-headed flying-fox for the 2003-2004 fruit season. Department of Environment and Heritage, Australia. [ http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/publications/pubs/grey-headed-flying-fox.pdf link to pdf - 341kb]

- Divljan A, Parry-Jones K, Wardle GM (2006) Age determination in the grey-headed flying fox, Journal of Wildlife Management, 70 (2) 607-611

- Eby, P. and Lunney, D. (2002) Managing the grey-headed flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus as a threatened species: a context for debate. In Managing the grey-headed flying fox as a threatened species in New South Wales, p 1-15, Eby P and Lunney D (Eds.), Mosman, Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia

- Eby, P. (1991) Finger-winged night workers managing forests to conserve the role of grey-headed flying foxes as pollinators and seed dispersers. In Conservation of Australia's forest fauna, p 91–100, Lunney D (Ed.), Mosman, Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia

- FFG (2016) Flora & Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Threatened List October 2016 pdf

- Hall, L. and Richards, G. (2000) Flying foxes: fruit and blossom bats of Australia. University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- Hall, L.S. (2002) Management of flying-fox camps: what have we learnt in the last twenty five years. In Managing the grey-headed flying-fox as a threatened species in New South Wales, p 215–244, Eby P & Lunney D (Eds), Mosman, Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia

- IUCN (2008) IUCN Red List, Grey-headed Flying-fox, Lunney, D., Richards, G. & Dickman, C. 2008. Pteropus poliocephalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T18751A8554062. [Accessed 12 January 2017].

- Lunney, D. & Moon, C. (1997) Flying-foxes and their camps in the rainforest remnants of north-east NSW. In Australia's ever-changing forests III, p 247–277, Dargavel J (Ed.), Canberra, Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University

- Martin, L. and McIlwee, A.P. (2002) The reproductive biology and intrinsic capacity for increase of the grey-headed flying-fox ''Pteropus poliocephalus'' (Megachiroptera), and the implications of culling. In Managing the grey-headed flying-fox as a threatened species in New South Wales, p 91-108, Eby P and Lunney D (Eds.), Mosman, Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia

- McDonald-Madden, E., Schreiber, E.S.G., Forsyth, D.M., Choquenot, D. and Clancy, T.F. (2005) Factors affecting the grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus:Pteropidae) foraging in the Melbourne metropolitan area, Australia, Austral Ecology, 30 (5) 600-608

- Menkhorst, P.W. (1995) Mammals of Victoria, distribution, ecology and conservation. Oxford University Press, Australia.

- NCC (2010) Nature Conservation Council of New South Wales, Flying-foxes Policy. Amended in 2010

- Nelson, J.E. (1965) Movements of Australian flying foxes (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera), Australian Journal of Zoology, 13, 53–73

- Parry-Jones, K.A. and Augee, M.L. (1991) The diet of flying-foxes in the Sydney and Gosford areas of New South Wales, based on sighting reports 1986–1990, Australian Zoology, 27, 49–54

- Ratcliffe, F.N. (1931) The flying fox (Pteropus) in Australia, CSIRO Bulletin, 53, 1–81

- Richards, G.C. and Hall, L.S. (1994) An action plan for the conservation of bats in Australia (Archived content). Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Canberra.

- Richards, G.C. and Hall, L.S. (1998) Conservation of Australian Bats – are recent advances solving our problems? In Bat Biology and Conservation, Kunz and Racey (Eds.), Smithsonian Institution

- Spencer, H.J., Palmer, C. and Parry-Jones, K. (1991) Movements of fruit bats in eastern Australia, determined by using radio-tracking, Wildlife Research, 18, 463-468

- Strahan, R. (1995) The mammals of Australia. Reed Books, Australia

- SWIFFT video conference (Oct 2012) Rodney van der Ree, Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology (ARCUE) talk to SWIFFT, 12 October 2012.

- Tidemann, C.R. & Nelson, J.E. (2004) Long distance movements of the grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus), Journal of Zoology, 263, 141-146

- Tidemann, C.R. (1999) Biology and management of the grey-headed flying-fox, ''Pteropus poliocephalus'', Acta Chiroptera, 1, 151–164

- Vanderduys, E., McKeown, A., Pavey, C.R., Martin, J., Caleyet, P. (2024) Grey-headed flying-fox population is stable – 10 years of monitoring reveals this threatened species is doing well. CSIRO Publishing 25 March 2024

- Van der Ree, R., McDonnell, M.J., Temby, I., Nelson, J. and Whittingham, E. (2006) The establishment and dynamics of a recently established urban camp of flying foxes (Pteropus poiliocephalus) outside their geographic range, Journal of Zoology, 268 (2) 177-185

- VBA (2017) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, Victoria. [Accessed 10 January 2017].

- Wahl, D.E. (1994) The management of flying foxes (Pteropus spp.) in New South Wales. Master’s thesis, University of Canberra, Australia

- Webb, N.J. & Tidemann, C.R. (1996) Mobility of Australian flying-foxes, Pteropus spp. (Megachiroptera): evidence from genetic variation, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 263, 497–502

- Westcott, DA, Heersink, DK, McKeown, A, Caley P (2015) The status and trends of Australia’s EPBC-Listed flying-foxes. CSIRO, Australia.

Personal Communications

- Braverstock, G., (2017) personal communication, Geelong Botanic Gardens.

- Davidson, M., Friends of Bats (Melbourne)

- Greengrass, K., Biodiversity Officer, Department of Sustainability and Environment

- Van der Ree R., Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology, Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, School of Botany, University of Melbourne

More Information

- Species profile and threats database Grey-headed Flying-fox Department of Environment & Energy, Australian Government.

- National Flying-fox monitoring viewer

- Bat ecology & conservation (SWIFFT video conference notes 26 July 2012)

- Flying-foxes in Victoria 2018 update pdf - Dr Rodney van der Ree Director – Ecology and Infrastructure International School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne.

- SWIFFT Seminar Notes - Living with flying-foxes in Victoria March 2024

- SWIFFT Seminar Notes - The establishment, growth and fluctuations of Grey-headed Flying-foxes in Victoria: challenges for the community and managers March 2024