Regent Honeyeater

Regent HoneyeaterAnthochaera phrygia | |

|---|---|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Meliphagidae |

| Status | |

| World: | Critically endangered (IUCN) |

| Australia: | Critically endangered (EPBC Act 1999) |

| Victoria: | Critically endangered (FFG Threatened List 2024) |

| South Australia | extinct |

| New South Wales | endangered |

| Queensland | endangered |

| FFG VIC: | Action Statement No. 41 (pdf) |

| Zoos Victoria Figthing Extinction priority species |

The Regent Honeyeater Listed under the Victorian FFG Act 1988 as Xanthomyza phrygia but now referred as Anthochaera phrygia is a medium sized bird of extraordinary beauty that has been driven almost to the brink of extinction by indiscriminate land clearing. It has no close relatives and is the only member of its genus. Traditionally thought to be related to highland Papuan honeyeaters of the genus Melidectes, on genetic evidence it is now believed to be closer to the familiar and common wattlebird group, genus Anthochaera.

Distribution & decline

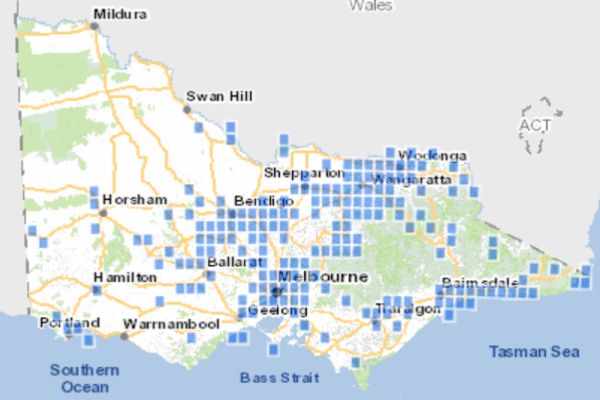

When European settlers first arrived in Australia, Regent Honeyeaters were common and widespread throughout the box-ironbark country of southeastern Australia, from about 100km north of Brisbane through sub-coastal and central New South Wales, Victoria inland of the ranges, and as far west as the Adelaide Hills. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, flowering eucalypt forests attracted immense flocks of thousands of birds.

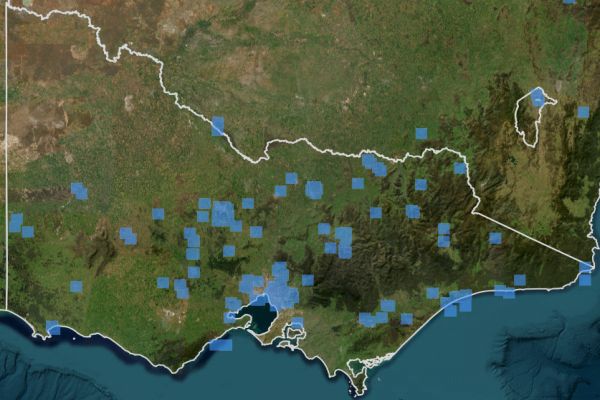

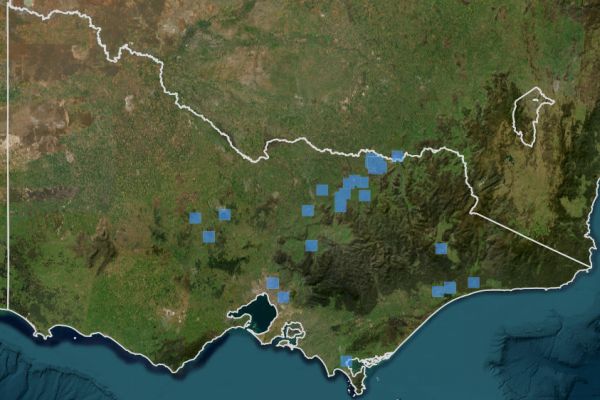

With the onset of broadacre clearing of its favoured box-ironbark habitat, however, the Regent Honeyeater declined rapidly. It is now extinct in South Australia and effectively so in western Victoria; it is a rare vagrant to the country around Bendigo (where it was once common) and to Gippsland (where it was a regular visitor), and in most years only a handful of birds are seen in eastern Victoria — four-fifths of sightings are from just three locations: Chiltern, the Killawarra, and the Reef Hills. Queensland now sees only irregular sightings of a small number of birds.

Across Australia there are only about 800 to 1500 Regent Honeyeaters in the wild, with about 100 of these remaining in Victoria.

Significant breeding populations remain only in New South Wales, primarily around the Capertee Valley northwest of Sydney on the inland slopes of the Blue Mountains and in the Bundarra-Barraba area north of Tamworth. Breeding is also reported from the country straddling the Murray River between Albury and Chiltern, and occasionally from other areas in particularly good seasons.

Habitat

Regent Honeyeatersare favour box-ironbark habitat which once extended from west of the Adelaide Hills right through inland Victoria and sub-coastal New South Wales into Queensland.

Regent Honeyeaters show a consistent preference for just four eucalypt species: Mugga Ironbark Eucalyptus sideroxylon, White Box Eucalyptus albens, Yellow Box Eucalyptus melliodora and Yellow Gum Eucalyptus leucoxylon. All four species flower profusely and have especially rich nectar flows.

Remnant vegetation on private land can contain valuable feeding and/or breeding resources for the Regent Honeyeater with specific migrations being made when there are seasonal flowering events. About 65% of all Regent Honeyeater records in the past decade come from private land.

Habitat decline

In most cases, generalist species which can adapt to a wide range of different conditions cope well with disturbance and habitat change: obvious examples include the various feral pests, and a number of native animals like the Common Brushtail Possum and the Noisy Miner.

Conversely, species which specialise in a particular environmental niche are highly vulnerable. Many specialised taxa are naturally quite rare because their preferred habitat is itself uncommon (the Mountain Pigmy Possum and the Helmeted Honeyeater are examples), others can be very common if their normal habitat is widespread. (Consider the Superb Fairy-wren, which requires dense cover for nesting and shelter close to open ground for feeding: this combination can be found almost anywhere, so the familiar blue wren remains one of the most common birds in southeast Australia.)

A large bird by honeyeater standards, the Regent is very active and requires an energy-rich diet to survive and breed successfully. In the past, this was amply provided: the gentle inland slopes of the Great Dividing Range and the nearby flats contained vast stands of nectar-rich eucalypt woodland. During the 19th and 20th centuries, most of this was cleared for agriculture, particularly the better-watered and more fertile areas, leaving only isolated patches of native vegetation. Most remnants occur on rocky, infertile soil that was not considered worthwhile clearing. Instead, remaining forest was used for timber production.

For the Regent, with its high-energy diet, the consequences were dire: the most fertile areas with the richest and most reliable nectar flows were turned into paddocks, and even the marginal low-fertility areas where trees remained were degraded by selective removal of mature trees (which produce good nectar flows) in favour of immature trees (which put most of their available resources into growth instead of flowering). There is no uncut old-growth box-ironbark woodland remaining in Victoria; the situation in New South Wales is less extreme but similar.

Ecology

Behaviour

Regent Honeyeaters are gregarious but are also often seen singly or in pairs. Larger groups tend to form around good food sources. Flocks of 50 to 100 were regularly reported in the early years of the 20th century; these are now rare. Of about 300 sightings recorded between 1988 and 1990, for example, 74% were of a pair or a single bird and just 3% of ten birds or more, with the largest flock numbering 23 individuals. Flocks can form at any time of year but are more common in winter.

Diet

Although primarily a nectar feeder, the Regent Honeyeater also takes lerps, insects and honeydew. Most foraging takes place high up in the canopy. Individual birds typically take temporary "ownership" of a single tree and chase off rivals of their own or other species.

Breeding

Regent Honeyeaters breed in simple pairs; although pairs will sometimes nest quite close together there is no evidence of cooperative breeding. Individual breeding pairs may or may not reform for subsequent seasons. Breeding is normally in the spring: mostly from August to October but it can be as early as June or as late as February. In Victoria, breeding tends to be later, typically November to January.

The nest is a sturdy but untidy cup constructed by the female, made of bark, grass, or other available plant material, bound with spider web, and usually placed in the canopy of a tree, though a range of heights from 1m to 30m have been recorded. Favoured locations support the base of the nest: vertical forks, a forked horizontal branch, or within mistletoe. Two eggs are usually laid, sometimes three, and are incubated by the female while the male defends the breeding territory. Incubation takes about two weeks.

Only the female broods nestlings after hatching, but both birds feed the nestlings on nectar, lerps, and invertebrates. The young fledge about 16 days after hatching, and begin foraging for themselves two weeks after that, although they continue to beg for and receive food for about another week before becoming completely independent.

A single brood is normal but good seasons with prolonged nectar flow can occasionally allow a second brood, usually not in the same location.

Actions for conservation of the Regent Honeyeater in Victoria

Conservation actions in Victoria are undertaken in line with a National Recovery Plan 1999-2003 and in conjunction with a Recovery Team comprising Victorian and interstate representatives. National Parks and Wildlife, New South Wales takes the lead role for the Recovery Plan which is under review. The Regent Honeyeater recovery team is administered by BirdLife Australia’s Woodland Birds for Biodiversity project with a Regent Honeyeater recovery co-ordinator. Funding for recovery actions has been through the Natural Heritage Trust Envirofund, Second Generation Landcare, and Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority.

A major component of the recovery effort is to implement a coordinated program of habitat protection and enhancement across the entire range of the species. A captive breeding and release program commenced in 1995 with the intention of being able to reintroduce Regent Honeyeaters into suitable habitat with the view of reinvigorating depleted populations though natural breeding in the wild.

Key Local Government Areas for conservation of the Regent Honeyeater in Victoria:

- Benalla Rural City

- Indigo Shire

- Mansfield Shire

- Murrindindi Shire

- Wangaratta Rural City

Priority Victorian locations for conservation activities

- Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park

- Lake Eildon National Park, Gobar Flora and Fauna Reserve and surrounding district

- Boweya Flora and Fauna Reserve

- Warby Range State Park

- Reef Hills State Park

At each of the priority locations Parks Victoria, DELWP and community groups participate in the twice annual national regent honeyeater count weekends being on 3rd weekend in May and the 1st weekend in August. Each area is monitored for outcomes of breeding attempts whenever nests are located.

Noisy Miner research in Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park

A research project has been developed to map the distribution and abundance of within the Chiltern-Mt. Pilot NP and surrounding roadsides. Planning and implementation of a pilot Noisy Miner control program in key Regent Honeyeater habitat within the Chiltern-Mt.Pilot National Park is scheduled for 2014/15 . This involves pre-control liaison with community groups, landholders and partner agencies.

Captive release program in box ironbark vegetation within the Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park

The first releases of captive bred Regent Honeyeaters into the wild took place in May 2008 with 27 birds being released. In May 2010 a further release of 44 captive bred Regent Honeyeaters was undertaken in the Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park. Twenty-three of these birds were fitted with transmitters and were tracked until batteries ran out in mid-July 2010.

On the 17th April 2013 a release of 38 captive bred birds which were reared at Sydney’s Taronga Zoo was undertaken at Magenta Mine on the northern side of the Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park. Twenty Five birds were fitted with transmitters and were monitored by DEPI staff and volunteers for the length of the battery life (approx 11 weeks).

All released birds have four uniquely colour coded leg bands that enable individual bird identification that can be linked back to Zoo breeding and genetics records. If observations of this species are being made and it is possible to see the leg bands please include this information in reports as it is extremely valuable to be able to identify individual birds.

The captive breeding and release project is a partnership between Birdlife Australia, DEPI, Parks Victoria and Taronga Zoo (and affiliated institutions) on behalf of the national Regent Honeyeater Recovery Team. Friends of Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park, Bird observers and Landcare also play an important role in monitoring Regent Honeyeaters.

Monitoring has found nearly an 80% survival 15 weeks post release. This indicates good chances of ongoing survival with landscape scale movements detected. Five of the 2010 release birds were confirmed alive in Chiltern in 2013. There have been nine breeding attempts from five pairs of captive released birds over the later part of the project period. In December 2013 a 10th and successful breeding took place.

In early November a pair traversed over 50km from Chiltern to Hamilton Park, near Glenrowan with 2 new chicks detected.

Key findings

Over the course of the release program the project team have demonstrated that:

- Captive reared birds can survive in the wild long term (many years) post release.

- Captive reared birds have the ability to move 100’s km across fragmented landscapes and return.

- Ex-captive females and males can breed in the wild and successfully recruit birds into the population.

- Ex-captive females can successfully mate with wild males and recruit birds into the population.

- Ex-captive males can successfully mate with wild females and recruit birds into the population.

2015 update

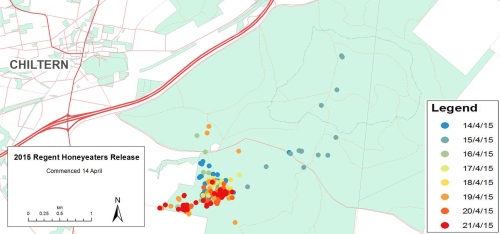

In April 2015, 77 Regent Honeyeaters were released into the Park with 39 birds fitted with radio transmitters. All bar one of the remaining 'leg bands only' Regents (a mysterious female wearing Black over Black) have been recorded. There is an intensive 7 day/week monitoring regime in place to monitor the released birds.

See: Regent Honeyater Captive Release Project updates

Release of Regent Honeyeaters April 2015 Source: DELWP

Tracking released birds

With the assistance of DELWP GIS, movements of the released birds has been tracked with one Regent travelling 5km to the north and returning back to base. The map demonstrates that the release site supports some of the best Ironbark flowering currently in the park.

See: Regent Honeyeater Captive Release Project for updated maps.

See the latest Regent Honeyeater updates

If you see a Regent Honeyeater please let us know

Regent Honeyeater ID guide

What to do if you see a Regent Honeyeater and online form

https://birdlife.org.au/what-to-do-if-you-see-a-regent-honeyeater/

Contact

- National Regent Honeyeater Recovery Co-ordinator, Mick Roderick, woodlandbirds@birdlife.org.au

References & Links

- Regent Honeyeater Conservation and Management Guide 2024 - Birdlife Australia

- Australian Government - Species Profiles and Threats Database, Regent Honeyeater

- FFG Threatened List (2024) Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 - Threatened List - May 2024 Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA).

- Regent Honeyeater - Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Action Statement No. 41

- Regent Honeyeater National Recovery Plan 2016

- BirdLife Australia (2023). Regent Honeyeater. updates sourced from: Marchant, S. et al (eds) 1990-2006 Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds.Volume 1 to 7.] Birdlife Australia.

- Regent Honeyeater Captive Release - updates on SWIFFT

- Regent Honeyeater project