SWIFFT Seminar notes 27 October 2022

Behaviour change

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 257 participants via Microsoft Teams. SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Also, thanks to Michelle Butler who chaired the session from Ballarat and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

Key points summary

An Introduction to Behaviour Change

- Achieving conservation outcomes is more about being able to persuade and change individuals rather than relying solely on the science.

- The more you understand and get to know your target audience the more you will be able influence behaviour, as you will have the ability to see things from another perspective.

- Specific messaging focusing on particular behaviours is more effective than generic messaging.

- Presuming to know what works in changing behaviour without doing the research can lead to poor outcomes.

- Multiple messaging techniques are more effective than staying with one strategy, particularly when targeting a large audience.

Shifting attitudes and support for Cultural fire practices

- Indigenous people are awakening an old land management practice that was sleeping for 3-4 generations.

- Cultural burning is a term used by the Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation to describe burning practices developed by Aboriginal people to enhance the health of the land and its people.

- Cultural burns in Wadawurrung language is Wiyn murrup – meaning fire spirit, as it brings a sense of ownership.

- Cultural burning (Wiyn murrup) is carried out to heal Country and may involve burning to create different fire intervals across the landscape. It can also be used for ceremonial purposes.

Human-wildlife conflict in Nepal

- Learnings from studying human-wildlife issues in Nepal are really about behaviour change and the way people can live with and look after wildlife.

- Subsistence farming communities in the rural areas of Nepal have to deal with tigers, leopards, elephants and other animals which can impact on their livelihoods and wellbeing.

- Government authorities are working with communities on a number of behaviour change programs.

- The Bengal Tiger is classified as Endangered by the IUCN. Since more stringent controls over hunting in Nepal’s National Parks, tiger numbers have increased from 121 in 2009 to 355 in 2022 across the country.

Motivating landholders in private land conservation

- About 70% of Australia is privately owned land which makes private land conservation a very important component of biodiversity conservation.

- We need to recognise there are multiple motivations for people to participate in private land conservation.

- We need to think about the satisfaction of being in private land conservation and the challenges to the long-term efficacy, particularly in relation to, support, changing land ownership and impacts from Climate Change.

- The National Biodiversity Market Scheme is a good opportunity to scale up biodiversity gains but can not be used in a compensatory way, we need to frame biodiversity positively and the scheme needs to operate as part of a multi policy mix.

List of speakers and topics

- An Introduction to Behaviour Change - Professor Liam Smith - BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University

- Shifting attitudes and support for Cultural fire practices - Tammy Gilson - Wadawurrung woman who also works as an Aboriginal Partnerships coordinator and Heritage Specialist for the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

- Human-wildlife conflict in Nepal - Professor Wendy Wright - Professor, Wildlife Conservation & Dean, Graduate Studies, Federation University

- Motivating landholders in private land conservation - Dr Matthew Selinske – Post Doctoral Researcher, ICON Science lab, RMIT University

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

An Introduction to Behaviour Change

Professor Liam Smith - BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University

Liam acknowledged the Traditional owners of the Wurundjeri Country from where he was presenting and acknowledged Elders past and present.

Liam introduced his presentation by talking about two specific examples of behaviour change; firstly, his experience in unsuccessfully trying to protect habitat for the Growling Grass Frog where he learnt that conservation is more about being able to persuade and change individuals rather than relying on the science. The second example related to his experience in a program aimed at getting people to turn light switches off when leaving a room.

Problems with our approaches

The audience we are trying to change does not necessarily care about or think like me, to change their behaviour you need to understand their behaviour rather than guess what they are thinking about.

The more you understand and get to know your target audience well, the more you will be able influence behaviour, as you will have the ability to see things from another perspective.

Common mistakes and assumptions

Liam used a number of examples to highlight four common mistakes and assumptions in behaviour change:

I know what the problem is – don’t assume anything, making assumptions can lead to poor behaviour change outcomes.

I am not sure what the behaviour is – specific messaging focusing on particular behaviours is more effective than generic messaging.

I know what works – assuming that information, knowledge or incentives can change people’s behaviour or telling people about the significance of a problem does not necessarily work.

I’ll just focus on one strategy – multiple messaging techniques are more effective than staying with one strategy, particularly when targeting a large audience.

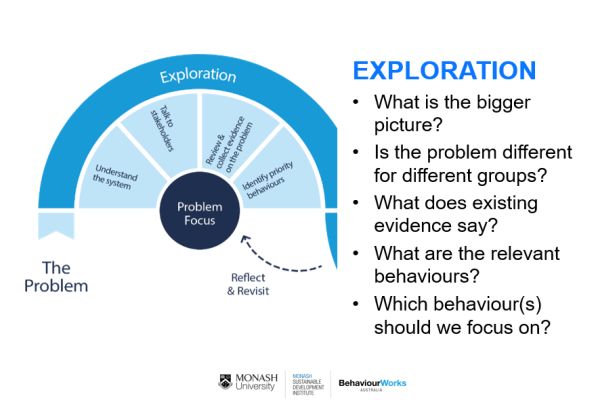

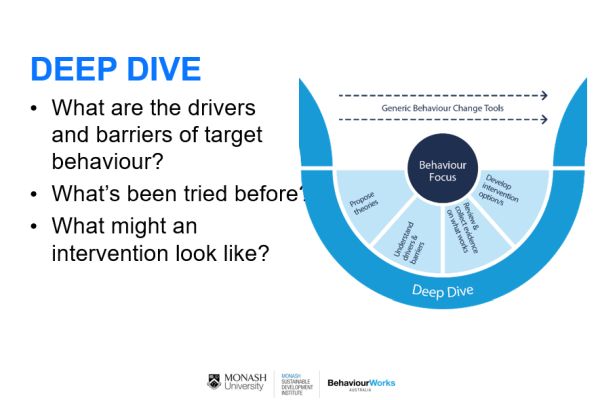

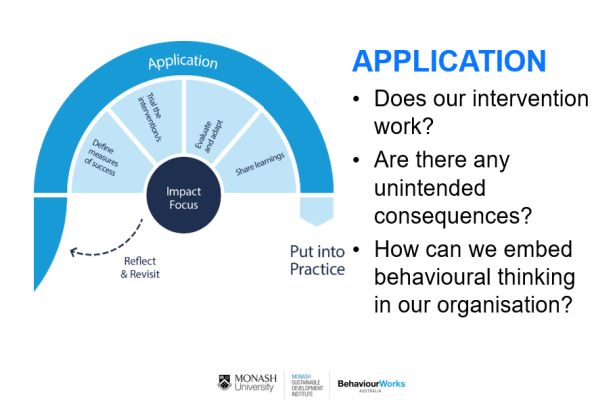

Designing better behaviour change programs

Liam discussed the process used by BehaviourWorks in designing ways to deal with behaviour change problems. He pointed out there is a free book which is an in-depth guide on how to use the BehaviourWorks Method.

Free book: the BehaviourWorks Method

https://www.behaviourworksaustralia.org/resources/the-method-book

Key Points from questions

- BehaviourWorks was founded about 12 years ago and has worked on about 700 projects around Australia.

- Working with community groups can yield good outcomes because they are trusted and are driven by the groups often with higher levels of engagement.

- The free book on the BehaviourWorks Method is very helpful for programs without a budget as it can help people in asking the right questions of themselves as they design their program.

A recording of Liam Smith's presentation to SWIFFT on 27 October 2022 from BehaviourWorks.

Shifting attitudes and support for Cultural fire practices

Tammy Gilson - Wadawurrung woman who also works as an Aboriginal Partnerships coordinator and Heritage Specialist for the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

Tammy acknowledged Wadawurrung Country which is the homelands of her ancestors. She paid respect to her ancestors, Elders who have walked before her and teachers of today. She also acknowledged all the ancestors and Elders of the Country where participants of the Seminar are located. Tammy also acknowledged all Aboriginal people and First Nations people present at the Seminar.

Fire Management in Victoria

The Regional Forest and Fire Operations Unit within DELWP leads and coordinates the planning and delivery of regional forest, fire and emergency management operations to provide environmental, economic and social benefits, and improve the safety of local communities.

Tammy spoke about the opportunities for policy and programs to be designed and delivered to better meet the needs of Traditional Owners in today’s world.

Cultural burning

Cultural burning may involve mosaic burning to create different fire intervals across the landscape or it could be used for fuel and hazard reduction. Fire may be used to gain better access to Country, to clean up important pathways, maintain cultural responsibilities and as part of culture heritage management.

Tammy pointed out Cultural burning can also be used as part of a ceremony to welcome people to Country or it could also be as simple as a campfire around which people gather to share, learn, and celebrate.

Walking in two worlds

Tammy spoke about her feelings, working in today’s busy world and also being a proud Aboriginal woman without opportunities to assert self-determination and care for Country how her ancestors did and who’s culture is sadly forgotten.

Tammy felt shifting mind sets within the department is sometimes a challenge when you change hats from a Traditional Owner to a DELWP hat. Tammy tries to embed awareness, proper engagement and Cultural safety in the roles she holds to support Traditional Owners. The more she embeds Culture at work the more behaviour shifts and with that comes respect.

Changing behaviour towards Cultural burning

Tammy spoke about a number points which are barriers that still exist regarding changing behaviour towards Cultural burning:

- Shifting attitudes

- Educating and knowledge

- Policy

- Accessibility to Country

- Walking in two worlds

- Language use

- Climate/weather conditions

- Funding

- Training

Tammy expressed her feelings about one of the main barriers for her; as Indigenous people are awakening an old land management practice that was sleeping for 3-4 generations. She felt the challenge of not only regaining knowledge of how and when to burn but encouraging Government bodies, agencies, community and the general public that Cultural burning is safe and has opportunity to benefit everyone.

Tammy reinforced that it is proven, Cultural burns safeguard hot fires from destruction as burns are carried out once every year until the Country starts to heal, after which the frequency can be reduced to every 2 years provided Traditional Owners are satisfied that the Country is healing.

Tammy highlighted that the Wadawurrung people see a name change as a behaviour change and have named their Cultural burns in Wadawurrung language, Wiyn murrup – meaning fire spirit as it brings a sense of ownership.

Victorian women’s Cultural Fire workshop

Tammy spoke about the first Victorian Aboriginal women's camp Wadawurrung Dja held in May 2022. A working group was formed with Firesticks Alliance and key knowledge holders in women’s fire from across the state in 2021. This paved the way for the camp and future workshops including a virtual Women’s Fire Forum on 4 November 2022 and workshops in 2023.

The purpose of the workshop was to inspire and build strong connections with other women across Victoria and deliver workshops for women only, as a collective continuing their journey in fire management.

Tammy discussed how knowledge was shared and cultural practices re-awoken to enable future leaders to share knowledge with future generations.

Tammy acknowledged the Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation, Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, sponsors Nation Partners’, Melbourne Water and Parks Victoria for their in-kind support. Without support and funding the workshop would not have been possible.

Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation

Wiyn murrup (Cultural burn) video taken at You Yangs Burn in 2022 with partners Parks Victoria and DELWP.

Human-wildlife conflict in Nepal

Professor Wendy Wright - Professor, Wildlife Conservation & Dean, Graduate Studies, Federation University

Wendy acknowledged the Gunaikurnai people, Traditional owners, Elders past and present of Gunaikurnai Country where she presented from. Wendy also acknowledged the Aboriginal Traditional Custodians of the lands and waters where Federation University campuses, centres and field stations are located.

Wendy introduced her talk by acknowledging the work by Babu Bhattarai who completed a PhD in Nepal on the losses of crops and livestock due to tigers and their prey.

Wendy pointed out that even though her presentation relates to human-wildlife issues in Nepal the message is really about behaviour change and the way people can live with and look after wildlife.

Human- wildlife conflict

Wendy spoke about the human-wildlife conflict issues facing people living in rural areas of Nepal, many are poor, subsistence farming communities who have to deal with not only large predators such as tigers and leopards but also large herbivores like elephants plus smaller herbivores e.g., deer, which can impact on their livelihoods and wellbeing.

Large predators such as tigers and leopards are known to kill livestock but tigers have also been known to kill people. ‘Problem tigers’ are tigers which have killed more than once inside a park boundary or have ventured outside of the park and killed someone in a village. Problem tigers are captured and removed to the Central Zoo in Kathmandu.

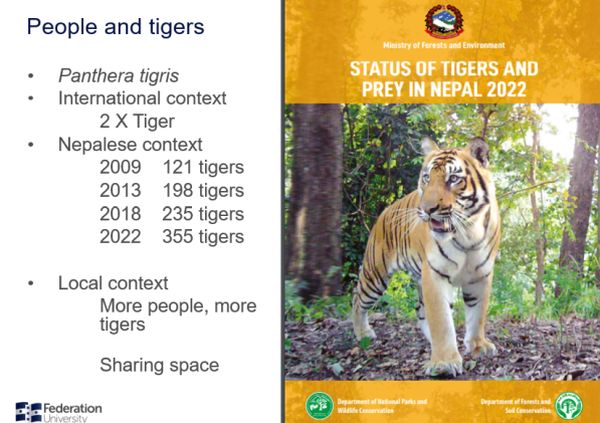

Bengal Tiger status and conservation

The Bengal Tiger, Panthera tigris, is classified as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN Red List 2022 ).

Wendy explained that in 2010 there were only about 3,200 tigers remaining in the World. In November 2010, an International Tiger Conservation Forum conference involving 13 tiger range countries was held in St Petersburg, Russia, the conference came up with a plan to double the numbers of tigers by the next “Year of the Tiger” in 2022.

Tiger conservation in Nepal

Nepal, being a signatory to the international agreement to double the number of tigers began cracking down on poaching inside its National Parks. The government also made the hunting of tiger prey species (deer and wild boar) illegal inside its National Parks. The Nepal Army has platoons based inside the parks and local communities formed community based antipoaching units.

Living with tigers

Wendy spoke about the life of farming communities in rural areas of Nepal and the close proximity of large predators and other potentially damaging wildlife which inhabit National Parks.

Wendy pointed out that as both the number of tigers and humans has increased since 2009 the level of potential human contact with tigers has also increased.

Research into losses of livestock and crops due to tigers and their prey species

Wendy spoke about the PhD study by Babu Bhattarai, who took leave from his position in the Nepalese Government’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation to investigated losses of livestock and crops due to tigers and their prey species.

Babu’s investigations found that local people, usually subsistence farmers bear significant economic losses associated with conservation, not to mention personal losses for human casualties. Farmers reported that 80% of stock losses were due to tigers but actual observations conducted over a year found that 94% of stock losses were due to leopards and only 6% due to tigers.

Wendy emphasised the importance of understanding the problem by collecting data. If we are trying to change behaviour towards tigers it is essential to know the reason behind the required behaviour change, in this case protecting stock from leopards not tigers. Further research is required to determine if increasing tiger numbers may be pushing leopards to the periphery of the parks thus increasing chances of stock predation.

Changing behaviours toward wildlife

Wendy spoke about the retaliatory killing of wildlife which occurs across the world where wildlife is in conflict with humans and farming, Australia being no exception. In Nepal, retaliation by local people after an attack on stock can result in the killing of wildlife either directly or by helping poachers to kill wildlife, undermining conservation efforts. Government authorities are working towards changing behaviour by introducing mitigation measures such as education regarding fencing and creating night shelters for stock. Other measures include capture and removal of large predators where attacks have occurred and appropriate compensation for legitimate stock loss.

Incentives to reduce the need for people to go into forests for thatch and fodder is a way of reducing wildlife – human interaction within the parks. The Government is also helping to develop alternative livelihoods such as wildlife guides with local people making a living from guiding, re-purposing their hunting skills to support ecotourism. Community based antipoaching units, particularly involving youth are also a way of supporting local communities to conserve wildlife.

Key points from questions

- Nepal is a densely populated country, being approximately the area as Victoria but with a population size comparable with Australia. People are condensed into the low country and hills so there is a lot of interaction between humans and wildlife.

- Elephants have distinct movement corridors so efforts are being made towards ensuring wildlife corridors are provided for elephants in the right locations.

- More research is required to fully understand the potential displacement of leopards due to the increased number of tigers.

Federation University - wildlife conservation research, People and Tigers in Nepal

Motivating landholders in private land conservation

Dr Matthew Selinske – Post Doctoral Researcher, ICON Science lab, RMIT University

Mathew acknowledged Wurundjeri Country and the people of the Eastern Kulin nations as the Traditional owners of the land where he works. He paid his respects to Elders past and present. Mathew also acknowledged Traditional owners and Elders on the lands of all the participants in the SWIFFT Seminar.

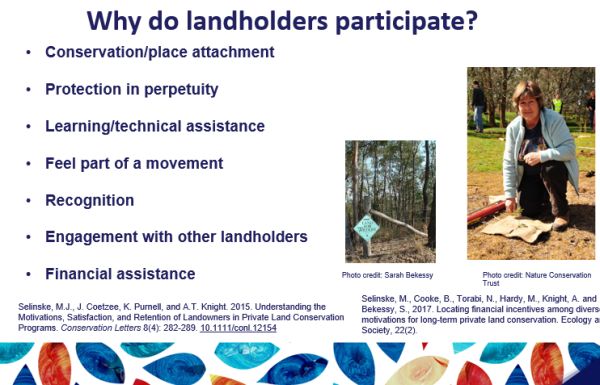

Mathew provided a brief introduction of his work in which he applies tools from the Behavioural Sciences and Social Sciences to focuses on conservation behaviour. He has a particular interest in private land conservation.

Importance of private land conservation

Mathew explained that 70% of Australia is privately owned land which makes private land conservation a very important component of biodiversity conservation. Australia has one of the longest formal ongoing programs for private land conservation. He pointed out there are multiple ways and programs for people to be engaged, e.g., Landcare, Land for Wildlife, Conservation covenants etc. Mathew also felt that private land conservation is not so much about behaviour change but more a behavioural reinforcement program.

Mathew highlighted that results from surveys of participants in land stewardship programs which found that participants expected greater support from the implementing organisation e.g., a stewardship officer with visits once per year. Change of ownership of covenanted properties can be a weak point if there is insufficient follow up and support provided to new landholders.

There are opportunities to implement Cultural burning on properties where burning would be beneficial but are beyond the resources and capability of the landholder.

Solutions to land stewardship

- Investment in outreach and stewardship engagement – technical assistance in grants for management, monitoring and enforcement of covenants.

- Support - building relationships between the coveting organisation, the landholder and the wider community. Building relationships is particularly important when new ownership of land takes place.

- Intergenerational stewardship – this is very powerful as it brings families together in a way that reinforces the conservation values of the land.

- Investment in social networks – landholders engaging in similar activities have the opportunity to learn together, have a mutual support system to share the highs and lows of land management.

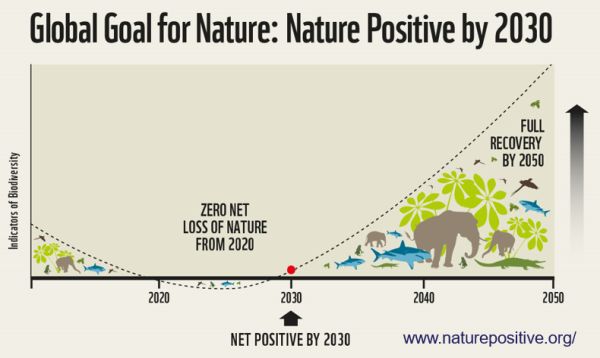

Global goal for Nature

Mathew spoke about the current policies and expenditures across the world for biodiversity conservation and conserving threatened species which are not working all that well. In Australia, we have the highest extinction rate in the world and are only spending about 15% of what is actually needed to avoid extinctions and recovery of threatened species.

National Biodiversity Market Scheme

In order to address the low financial commitment to nature conservation the Federal Government announced a National Biodiversity Market Scheme in August 2022, similar to the emissions reduction fund for carbon. Creating a market is a behaviour change incentive which provides landholders with a financial incentive to enhance biodiversity.

Mathew spoke about the biodiversity market being in a development stage at present, there is an opportunity to plan it as a behaviour change intervention to shape the market using the same steps as in the Behaviourworks model.

Mathew felt a successful biodiversity market should not include biodiversity off-sets; it should focus on incentivising a positive enhancement to biodiversity rather than a compensatory scheme being compliance driven. The biodiversity market should view biodiversity as an asset rather than a regulatory problem to deal with as an off-set. It should also have a robust monitoring and evaluation framework, timelines, a target and actions at both a national scale and local project level scale with the aim being net gain, a positive for nature.

Mathew pointed out that using a single instrument to protect nature is misguided. We need multiple behaviour change strategies; regulation of business, incentives, private sector investment and Government investment to support biodiversity conservation.

Key points from questions

- Costs associated with managing land for biodiversity can vary depending on the condition of the landscape, the state of biodiversity present and the level of restoration required.

- Production landholders can gain benefits from investing in biodiversity through enhanced ecosystem services.

- Programs need to invest in landholders undertaking biodiversity gains by providing on-going support to them as future stewards of the land.

- Many people who join biodiversity related programs are already engaged and want to scale up their conservation activities for their own personal values.

References

Selinske, M.J., J. Coetzee, K. Purnell, and A.T. Knight. 2015. Understanding the Motivations, Satisfaction, and Retention of Landowners in Private Land Conservation Programs. Conservation Letters 8(4): 282-289. 10.1111/conl.12154

Selinske, M., Cooke, B., Torabi, N., Hardy, M., Knight, A. and Bekessy, S., 2017. Locating financial incentives among diverse motivations for long-term private land conservation. Ecology and Society, 22(2).

Selinske, MJ, Howard, N, Hardy, MJ, Fitzsimons, J, & Knight, AT. 2019 Monitoring and evaluating the social and psychological dimensions that contribute to privately protected area program effectiveness. Biological Conservation 229: 170-178

Selinske, M.J., N. Howard, J.A. Fitzsimons, M. Hardy, & A.T. Knight. 2022. “Splitting the bill” for conservation: Perceptions and uptake of financial incentives by landholders managing privately protected areas. Conservation Science and Practice, e12660. 10.1111/csp2.12660”

ICON Science lab, RMIT University

Mathew Selinske publications https://matthewselinske.com/my-research/

Previous SWIFFT Seminars with Indigenous Cultural themes

- Cultural Protocols, Threatened Species and Traditional Knowledge

- Two ways of knowing natural temperate grasslands of the Victorian Volcanic Plain

- Returning Dja Dja Wurrung to the landscape

- Gunditjmara fish, mussels & crayfish

- Indigenous knowledge of ecology

- Indigenous Fire Workshop, Cape York

- Aboriginal waterway assessments

- Barapa Barapa Water for Country project

Notes from previous SWIFFT Seminars