SWIFFT Seminar notes 25 May 2023

Marine biodiversity conservation in Victoria

SWIFFT seminar notes are a summary of the seminar and not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

This SWIFFT seminar was conducted online with 175 participants via Microsoft Teams. SWIFFT wishes to acknowledge support from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), Victoria in organising the seminar and thank speakers for their time and delivery of presentations. Also, thanks to Michelle Butler who chaired the session from Ballarat and acknowledged Traditional owners, Elder’s past and present on the lands covered by the meeting.

This seminar highlights the incredible marine biodiversity in Victoria and efforts to manage and protect marine biodiversity through research, legislation, Marine National Parks and restoration projects.

Key points summary

Filling gaps in our knowledge of Victorian marine species: solving spider crab mysteries

- Spider crabs are Arthropods (invertebrate animals with a hard exoskeleton and jointed legs), aggregations occur in winter and also at a time when they moult.

- Recent research has found Spider Crab aggregations can occur in many different parts of Port Phillip Bay, and even as far as Western Port Bay and Gippsland Lakes.

- Spider Crab aggregations at St Leonards have been estimated to be in the order of 31,012 - 50,729 spider crabs with density up to 79 crabs per square meter.

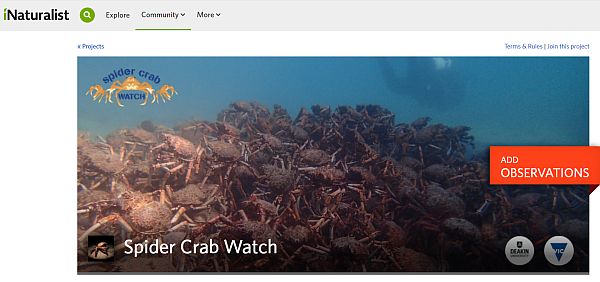

- A great deal of information needs to obtained to better understand the ecology of spider crabs. People can help through Citizen Science by contributing observations of spider crabs and their behaviour to Spider Crab Watch by using iNaturalist.

Victoria’s marine and coastal planning and management system

- Victoria’s Marine and Coastal Act 2018 provides a holistic system for planning and management across Victoria’s marine and coastal environment. The Act is implemented through a range of tools applied at a State-wide, Regional and Local scale.

- State-wide tools include; Marine and Coastal Policy, Marine Spatial Planning Framework, Marine and Coastal Strategy, State of the Marine and Coastal Environment Report and Guidelines.

- Regional tools include; Regional and Strategic Partnerships and Environmental Management Plans.

- Local tools include; Coastal and Marine Management Plans, Consents to use or develop marine and coastal Crown land.

- CoastKit portal is an online mapping portal which can be used to explore and visualise Victoria’s marine, environmental and coastal data.

Victoria’s Marine National Parks and Sanctuaries - twenty year of protecting marine biodiversity and ecosystems

- 20 years ago, Victoria created a network of marine national parks and sanctuaries to protect representative examples of Victoria’s marine biodiversity and ecological process for future generations.

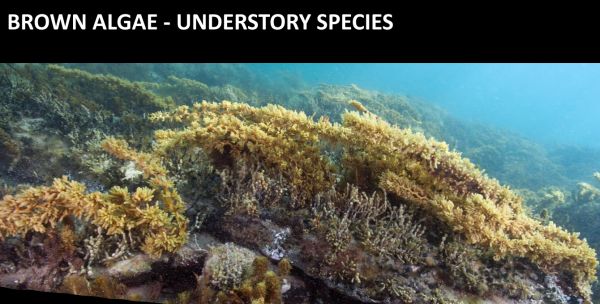

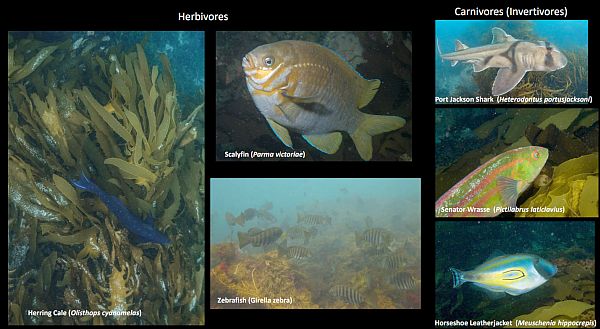

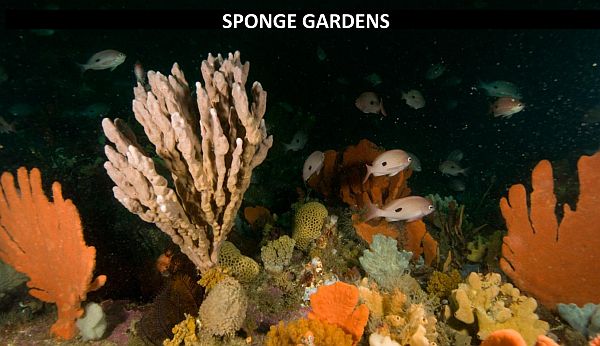

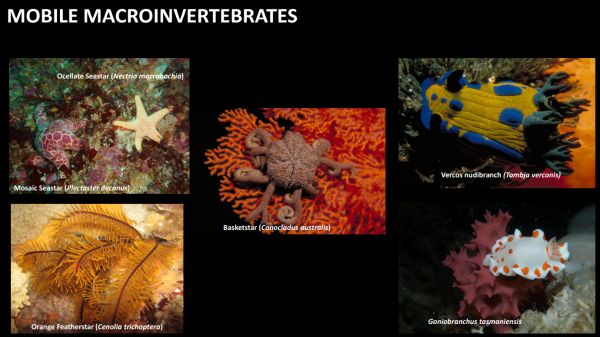

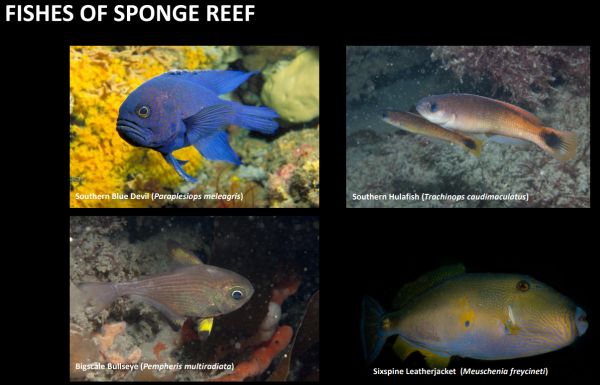

- Victoria has unique underwater habitats supporting incredible marine biodiversity; forests of brown, red and green algae in the shallow waters, magnificent sponge gardens in the deep waters, sandy plains and seagrass meadows in bays and inlets.

- Long-term monitoring of species richness and populations of selected species inside and outside of the parks has found the parks have been effective in protecting a range of marine biodiversity but there is a need to understand the challenges from future threats such as climate change.

Restoring shellfish reefs on Gippsland Lakes

- Reef Builders shellfish restoration projects have been successful but it would be far better and in the long-term more economical to preserve and protect the loss of shellfish habitat in the first place rather than have to undertake restoration.

- Over-harvesting has resulted in a collapse of the flat oyster ecosystem in Victoria with a 95% loss of the Australian Flat Oyster and Blue Mussel reefs in Victoria since European settlement.

- The restoration site at Nyerimilang in Gippsland Lakes involved 2,000 tonnes of limestone used to create 17 reef patches in a 3-ha area with a total reef footprint of 4,500 square meters.

- It is estimated around 9 million mussels are now growing on the new reefs and about 3 1/2 million native flat oysters have been reseeded on the new reef.

- When the reefs are fully established in 3 – 5 years time, around 400 million litres of water per day will be filtered.

List of topics and speakers

- Filling gaps in our knowledge of Victorian marine species: solving spider crab mysteries - Dr Elodie Camprasse – Deakin University

- Victoria’s marine and coastal planning and management system - Nicola Waldron – Manager Policy & Strategy, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

- Victoria’s Marine National Parks and Sanctuaries - twenty year of protecting marine biodiversity - Dr Michael Sams – Parks Victoria

- Restoring shellfish reefs on Gippsland Lakes - Scott Breschkin – Oceans Project Coordinator, The Nature Conservancy

SPEAKER SUMMARIES

Speaker summaries are adapted from presentations and are not intended to be a definitive record of presentations made and issues discussed.

Filling gaps in our knowledge of Victorian marine species: solving spider crab mysteries

Dr Elodie Camprasse – Deakin University

Elodie acknowledged the traditional owners of the Wurundjeri, Wathaurong and Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation covering the lands and waters where the Spider Crab project is being carried out.

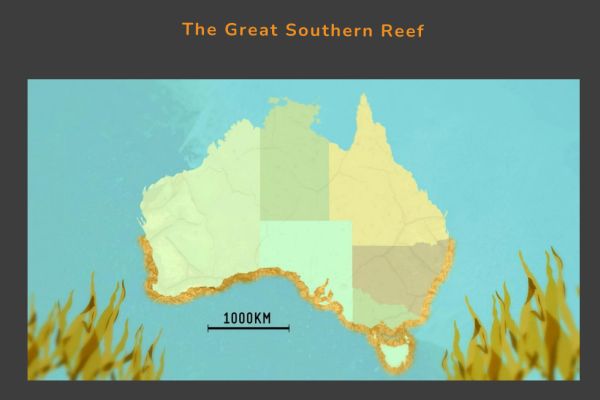

Great Southern Reef

Elodie spoke about the Great Southern Reef which is an interconnected series of reefs across southern Australia extending south of Brisbane, Queensland and Kalbarri in Western Australia to Tasmania. The Great Southern Reef covers around 8,000 km of coastline incorporating 5 states with an area of 71,000 km² of ocean.

As well as supporting unique biodiversity, the Great Southern Reef and the waters of Victoria also contain amazing natural spectacles, for example Spider Crab aggregations.

Studying Spider Crab aggregations

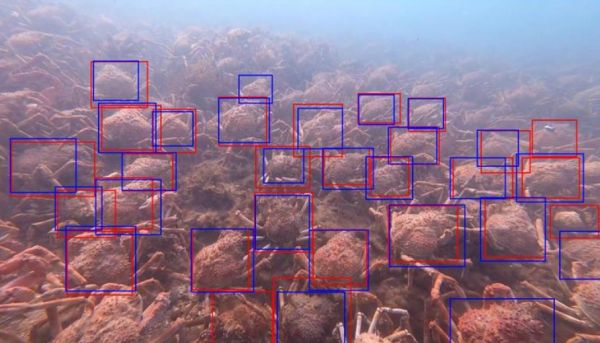

Divers undertake surveys of spider crab aggregations to determine numbers and learn about the ecology of the crabs. Image source: Elena Markushina.

Historically, Spider Crab aggregations have been observed in Port Phillip Bay in the waters of the Mornington Peninsula, particularly in the Rye / Blairgowrie area. More recent studies have found spider crabs can occur in many different parts of Port Phillip Bay, and even as far as Western Port Bay and Gippsland Lakes.

Spider crabs are Arthropods (invertebrate animals with a hard exoskeleton and jointed legs), aggregations occur in winter and also at a time when they moult (shedding their hard structure to grow and form a new outer hard exoskeleton). The Spider Crab is vulnerable to predators for a few days during the moulting process until its new outer shell becomes hard. Predators such as the Smooth Stingray, Port Jackson Shark, other rays and fish have been observed close to aggregations.

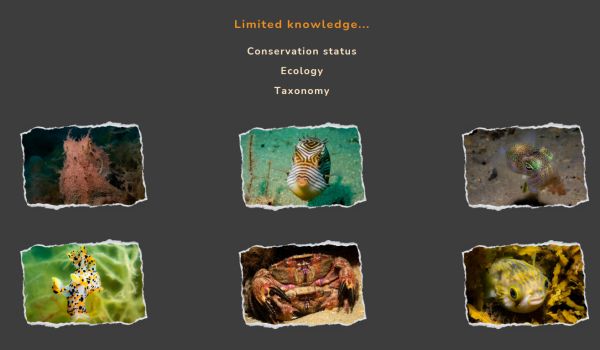

Very little is known about Spider Crabs

Elodie spoke about some of the frequently asked questions which need to be answered to ensure conservation of this species:

- Where do they come from?

- What triggers the aggregations?

- How long do the aggregations last?

- Why do they gather at other times?

- How many Spider Crabs are there?

- How important are the aggregations for other species?

Spider Crab Citizen Science project

Spider Crab Watch uses iNaturalist as a means of enabling Citizen Scientists to contribute their observations to the project. This project has replaced the old Spider Crab Melbourne web page.

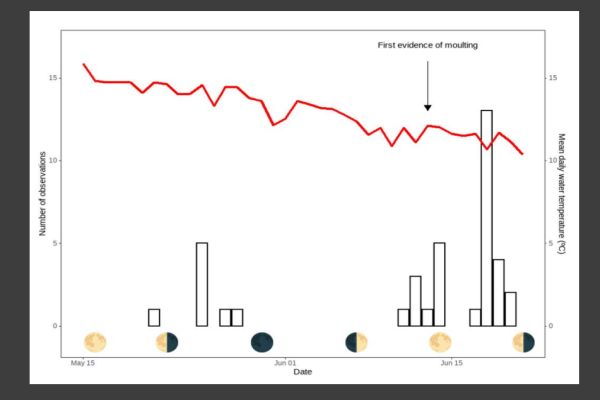

Spider Crab population study

Elodie explained the process of estimating the number of spider crabs during an aggregation at a particular location. Stereo diver operated video transects are taken across the aggregation. Some of the images are used to labelled individual spider crabs by hand which can be applied to machine learning algorithms to count crabs from the video transect (red and blue boxes).

Data from the transects at St Leonards in 2022 found densities of crabs between 0 - 79 crab/m² with an aggregation size between 1420 - 2104 m² and spider crab numbers 31,012 - 50,729.

Identifying the presence of spider crabs

Timelapse cameras have been deployed on piers at Rye and Blairgowrie, these are known aggregation sites to collect information on the presence of spider crabs. The cameras took an image every 5 minutes in daylight hours with over 66,000 images taken. The images were sorted through to determine which images contained Spider Crabs. Citizen Scientists can help with the analysis of timelapse images by using the Zooniverse app or web site. There are three workflows in which people can contribute; 1. identifying images with spider crabs, 2. Identifying human activity from the images, 3. Recording the presence of other marine life.

Citizen Scientists can help with the analysis of time lapse images by using the Zooniverse app or web site. Spider Crab Watch - Zooniverse

Tagging

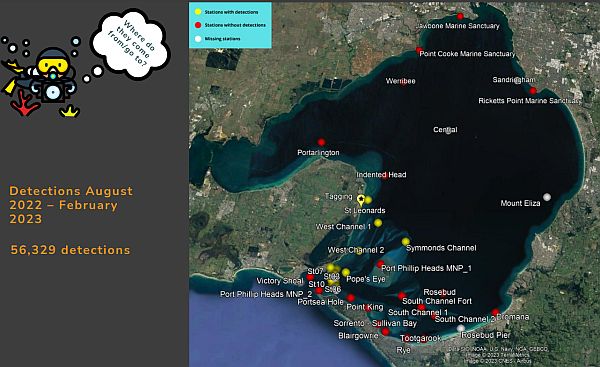

Elodie spoke about the tagging project in which 50 spider crabs were fitted with a unique tag which could be detected by any one of 44 listening stations around Port Phillip Bay. Between August 2021 and February 2022 there were detections of 27 crabs across 13 stations.

Deakin University Spider Crab research.

Elodie thanked all the partners and support for the project. She also acknowledged the project team at Deakin University: Assoc. Prof. Daniel Ierodiaconou, Dr Elodie Camprasse, Prof. John Arnould, Paul Tinkler, Dr Mary Young, Darren Wong, Dr Sasha Whitmarsh, Scott Gray, Darcy Cutter.

Contact: Elodie Camprasse

@ECamprasse

Contribute observations at Spider Crab Watch or help the team classify images from timelapse cameras from home on Zooniverse.

Key points from questions

The winter aggregations at Rye and Blairgowrie are not the only Spider Crab aggregations that occur in Port Phillip Bay which means other aggregations are not well known and are most probably subject to less disturbance or harvest than the well-known sites.

At this point it is difficult to say what the human impact on spider crabs might be as more work is required to determine the overall population and movement.

At this time, it is not known if light pollution is an issue for spider crabs. This is just one of many questions to be solved through more research but it is difficult to get funding for marine research.

Photos of sharks interacting with spider crabs would be valuable information as more work needs to be undertaken to understand predation during the moulting season.

At present, all the published literature refers to spider crabs only occurring in Victoria and Tasmania but there have been reports of Spider Crab aggregation in South Australia. This only highlights the lack of knowledge about this species.

It is not known if there are separate aggregations for moulting and breeding, however it is known that the shell has to be soft for mating and that there have been only incidental observations of mating.

More research is required to determine if moon phases have any influence on the moulting or breeding times of spider crabs.

It is not known how spider crabs communicate to form aggregations but it is thought to be more of a chemical cue rather than visual.

Victoria’s marine and coastal planning and management system

Nicola Waldron – Manager Policy & Strategy, Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

Nicola introduced her presentation by acknowledging the traditional owners of Victoria’s lands and waters.

Marine and Coasts policy and planning

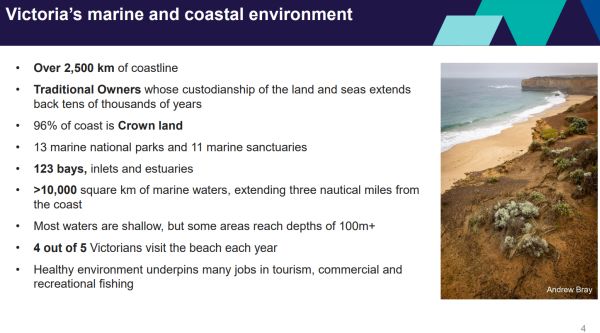

Nicola provided an overview of the policy and planning process and the importance of science and data feeding into science-based policy and planning. Nicola also spoke about the complexity of demands and uses of the coastal environment.

Nicola showed a diagram which illustrated the complex range of values and uses in the marine and coastal environment. The Marine and Coastal Act 2018 provides valuable tools for the management of Victoria’s biodiversity as well as the wide range of uses and values in the marine environment. Nicola also discussed some of the challenges facing the marine environment including climate change, population growth, pollution and extraction of resources. Addressing these challenges requires collaboration across sectors and strategic approaches.

https://www.marineandcoasts.vic.gov.au/

Marine and Coastal Act 2018

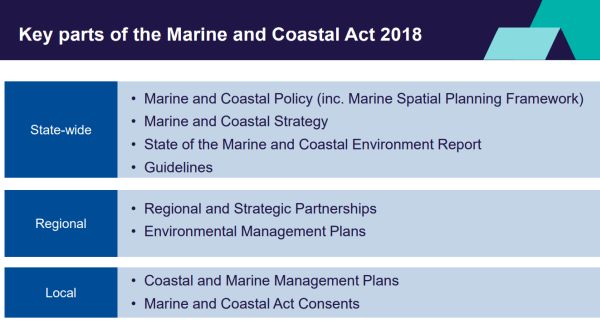

The Marine and Coastal Act 2018 provides a holistic system for planning and management across Victoria’s marine and coastal environment. The Marine and Coastal Act works in partnership with a range of other Acts applying to Victoria’s marine waters, which focus on specific activities and areas of the marine and coastal environment, e.g., legislation applying to traditional owners, Crown Land reserves, flora and fauna, ports management and fisheries management.

Nicola spoke about the State-wide, Regional and Local scale of implementing the Marine and Coastal Act and the tools provided for by the Act.

At the State-wide level the Act provides an integrated whole of Government policy and strategy.

At the Regional level there are a number of Environmental management plans e.g., Port Phillip Bay Environmental Management Plan.

At the Local level there are a number of Coastal and Marine Plans which support the integration of the State-wide policy and strategy into local management objectives. Ministerial consent is applied to works on marine and coastal Crown Land. There are also regulations which are aimed at streamlining approvals.

STATE-WIDE TOOLS

Marine and Coastal Policy

The Marine and Coastal Policy commenced on 6 March 2020 and has a 15-year life. The Policy sets the vision and long-term outcomes for the planning and management of our marine and coastal environment.

Marine and Coastal Policy 2020 pdf

“Our vision is for a healthy, dynamic and biodiverse marine and coastal environment that is valued in its own right, and that benefits the Victorian community now, and in the future”.

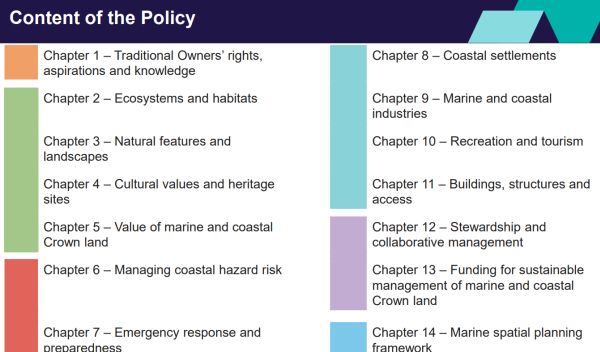

The Marine and Coastal Policy contains 14 chapters which relate to various aspects of marine and coastal planning. The Policy provides guidance to decision-makers to meet objectives and guiding principles of the Marine and Coastal Act 2018. The Policy establishes a planning and decision pathway that helps decision makers apply the Act’s objectives. The Policy also includes a Marine Spatial Planning Framework, as required under the Act.

Marine Spatial Planning Framework (Chapter 14 of the Marine and Coastal Policy)

Marine Spatial Planning provides guidance and process to achieve integrated and coordinated planning. It supports long-term, strategic planning across sectors in relation to the marine environment (e.g., Fisheries, Ports and Shipping. The process has two parts:

Part A – policies and guidance

Part B – approach to marine spatial planning (output: marine plan)

More about Marine Spatial Planning

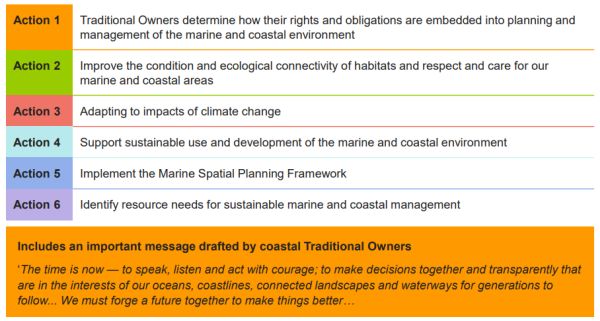

Marine and Coastal Strategy

The Marine and Coastal Strategy is the first Strategy under the Act, released May 2022. It identifies six priority actions critical to achieving the vision and intended outcomes of the Policy. Delivery of the six actions through 54 activities with identified timeframes and leads, over the next 5 years.

More information on Marine and Coastal Strategy

State of the Marine and Coastal Environment Report

The State of the Marine and Coastal Environment Report has a 5-year reporting cycle. The first report was delivered by the Commissioner for Environment and Sustainability in 2021.

The report assesses 82 indicators of ecosystem health and social science, across nine themes:

- Water quality and catchment inputs

- Litter and pollution

- Biodiversity

- Seafloor integrity and health

- Pests and invasive species

- Climate and climate change impacts

- Managing coastal hazard risks

- Communities

- Stewardship and collaborative management

Guidelines

Nicola explained how the Marine and Coastal Act 2018 allows for guidance on any matters relating to implementation of the Act. E.g., Guidelines for siting and design of structures on the coast (released in 2020).

Guidance is currently being finalised for:

- Marine Spatial Planning

- Coastal hazard adaptation (Victoria’s Resilient Coast – Adapting for 2100+)

- Coastal and marine management planning

REGIONAL TOOLS

Nicola spoke about some of the regional tools under the Marine and Coastal Act 2018:

- Regional and Strategic Partnerships - designed to address issues that cross management boundaries E.g., Cape to Cape Resilience Project.

- Environmental Management Plans - the contents of an EMP must include actions to improve water quality, protect beneficial uses and address threats in the area the plan applies to Port Phillip Environmental Management Plan.

LOCAL TOOLS

Applied under the Marine and Coastal Act 2018:

- Coastal and Marine Management Plans (CMMPs) – these provide direction for management of an area of marine and coastal Crown land. They can cover multiple coastal Crown land reserves and land managers.

- Consents – used at a site level where consent from the Minister (or delegate) is required to use or develop marine and coastal Crown land. Applications for consent are assessed against the Policy, Strategy and any regional or local planning tools relevant to the area.

CoastKit

Nicola highlighted the CoastKit portal an online mapping portal which can be used to explore and visualise Victoria’s marine, environmental and coastal data. Nicola pointed out the portal is regularly updated; it can be a valuable tool for researchers or members of the public or proponents of projects on coastal Crown land to understand what information is available on the coastal and marine environment.

Feature Activity Sensitivity Tool – developed by Deakin University this is a new feature is part of CoastKit. It is Victoria’s new first-pass environmental risk assessment tool which can be used to assist in pre-application planning and approvals processes under the Marine and Coastal Act and Environment Effects Act in areas within 3 nautical miles of the coastline.

Key points from questions

Enforcement of Consent of works on coastal Crown land is carried out though authorized officers in the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Change (DEECA) and land managers.

Development of off-shore windfarms falls under the Marine and Coastal Act 2018 and tools such as Marine Spatial Planning can support sustainable development of that industry.

Roll out of the new tools in the Marine and Coastal Act 2018 is an adaptive process, including pilot projects which are being evaluated to identify challenges and see where things are working. Feedback from people is important as use of the tools evolves.

Contact: Nicola Waldron DEECA

Victoria’s Marine National Parks and Sanctuaries - twenty year of protecting marine biodiversity

Dr Michael Sams – Parks Victoria

Twenty years ago, Victoria created a network of highly protected (no- take) marine national parks and sanctuaries to protect representative examples of Victoria’s marine biodiversity and ecological process for future generations.

Victoria’s Marine National Parks & Sanctuaries (no-take areas - in dark blue) comprise about 5.6% of Victorian waters and about 6.4% is protected in multi-use parks (light blue).

More details from Parks Victoria - Interactive map of marine protected areas in Victoria

Overview of Victoria’s marine biodiversity

Michael spoke about one of the major challenges to conservation being the general lack of understanding and awareness about the special and unique marine biodiversity in Victoria. Michael provided an exceptionally interesting overview of Victoria’s marine environment.

Underwater forests

Red algae

Sponge gardens

Sandy plains

Seagrass meadows

What have our Marine Protected Areas achieved for biodiversity in 20 years?

Michael spoke about the long-term monitoring program to evaluate how the marine parks system has performed over the years. This work has been in collaboration with a range of research partners.

Species richness

One of the measures is species richness (number of distinct species in a defined area) and comparing results inside and outside the protected areas of parks.

Michael showed several slides demonstrating results of species richness for fish and invertebrates with comparisons inside and outside of parks. The results demonstrate a higher level of species richness inside the parks compared to outside the parks.

Population monitoring

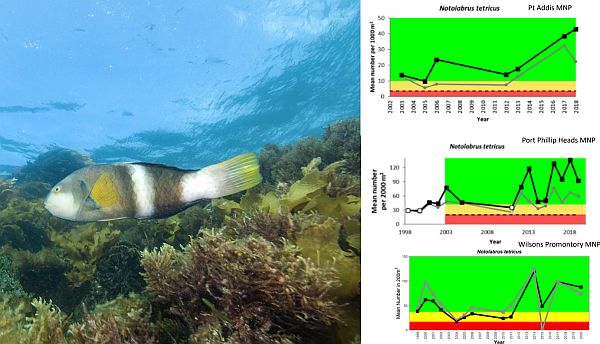

Michael explained the work on monitoring a selected number fish and invertebrate species inside and outside of the parks over the last 20 years to determine the long-term trend of those species.

Example of species monitoring (Blue-throated Wrasse) for over 20 years inside and outside of parks. Michael pointed out this species is a common and widespread species subject to relative high levels of recreational fishing pressure. The monitoring program demonstrated this species has benefited from Marine National Parks in Victoria.

Michael spoke about a number of other species which are part of the long-term monitoring inside and outside of the parks. E.g., Scalyfin, Yellow Striped Leatherjacket, Horseshoe Leatherjacket and Sea Sweep. Michael pointed out these species all ecologically quite different in their mode of feeding and prey. Depending on the point in time numbers can vary but overall, there are higher numbers of these species inside the park system.

The Marine National Parks have benefited invertebrate species. Michael used the example of Southern Rock Lobster surveys inside and outside the park at Point Addis where it has been found there is a greater abundance of larger male lobsters inside the park compared with outside and a much higher number of female lobsters inside the park compared to outside the park.

Surveys of Abalone across a number of parks across Victoria indicate a decline both inside the parks and outside the parks, the decline being more pronounced in the central and western parts of Victoria. As well as direct fishing pressure on abalone, Michael pointed out the decline could be due to the abalone virus and loss of brown algae forests.

Decline in large canopy forming brown algae species has occurred at a number of the monitoring sites over the last 20 years. Michael attributed the declines in the central and eastern parts of Victoria due to an over-abundance of urchins causing overgrazing. In the western part of Victoria, the loss is more likely to be associated with warming sea surface temperatures and increasing wave energy in response to clime change.

Michael summarised by emphasising the Marine National Parks contain a spectacular level of marine biodiversity. The parks have been effective in protecting a range of marine biodiversity but there is a need to understand changes from future threats such as climate change.

More details:

Parks Victoria Technical Series

Marine National Parks and Sanctuaries (resources and webinar series

Exploring Marine National Parks and Sanctuaries – Parks Victoria

Key points from questions

The Victoria’s marine protected areas do a good job of providing a good representativeness of marine habitats across Victoria.

Adding new marine protected areas is not the role of Parks Victoria. Michal emphasised PV is focused on their role of management of existing parks. Any expansion needs to be driven by the community and legislators.

Compliance in marine parks is carried out by PV officers and to a greater extent by Fisheries Officers. Community support and valuing marine protected areas by the community plays a major role their protection.

There was a significant loss of macroalgae species in Port Phillip Bay associated with the millennium drought, most probably due to less nutrients and higher water temperatures.

Restoring shellfish reefs on Gippsland Lakes

Scott Breschkin – Oceans Project Coordinator, The Nature Conservancy

Scott acknowledged the Gunaikurnai people as the traditional owners of the sea Country where the shellfish reef restoration project is carried out.

Scott introduced his presentation by highlighting the fact that whilst shellfish restoration projects have been successful it would be far better and in the long-term more economical to preserve and protect the loss of shellfish habitat in the first place rather than have to undertake restoration.

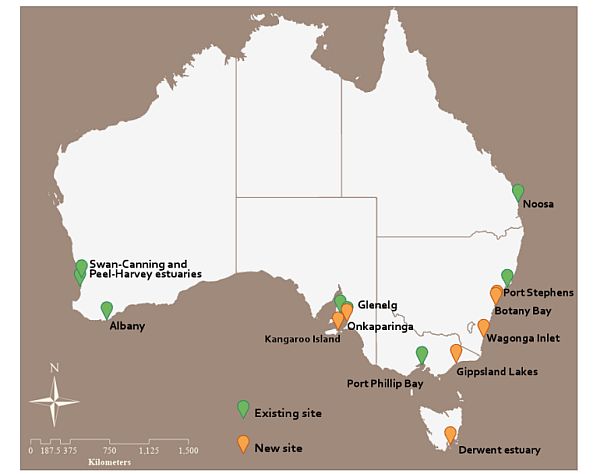

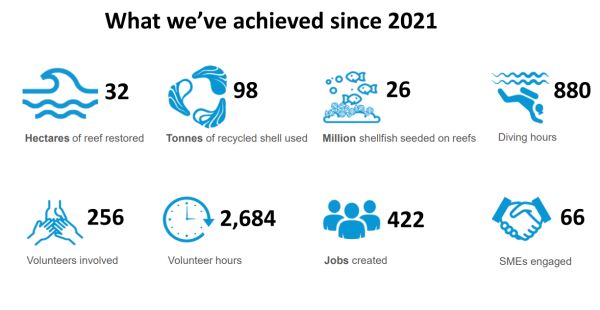

Reef Builder – Australia’s largest marine restoration initiative

Reef Builder is a partnership with the Australian Government and commenced in 2021. Other partners include; Local Government, Fisheries Authorities, other not for profits and Natural Resource Managers.

Reef Builder is undertaking shellfish restoration at 60 locations around Australia by 2030 bringing a once lost ecosystem back from the brink of extinction. It is Australia’s largest marine restoration initiative and a World first to recover endangered shellfish ecosystems in such a large scale.

The Gippsland Lakes project builds on an earlier shellfish restoration project in Port Phillip Bay in 2017 which demonstrated successful outcomes. Scott highlighted that the Reef Builder project in Gippsland Lakes provides important economic relief post-COVID and the 2019 bushfires.

Shellfish reef restoration involves building complex three-dimensional reef structures supporting shellfish. Projects around Australia include a number of species; Sydney Rock Oysters, native Flat Oysters, Blue Mussels and Black Pygmy Mussels across intertidal and subtidal environments.

Decline of native Australian Flat Oysters

Scott spoke about the discovery and exploitation of oyster reefs in Australia.

Oysters were also taken for their food value. In the 1850’s some of the main oyster harvesting areas were Western Port Bay and Port Phillip Bay. In Western Port Bay estimates of 10 tonnes of oysters per week were being harvested and sent to Melbourne.

In Victoria, over-harvesting led to a collapse of the oyster ecosystem with a 95% loss of the Australian Flat Oyster and Blue Mussel reefs in Victoria since European settlement. These types of reefs are now considered functionally extinct in Victoria.

Present day efforts are now focused on recovery of shellfish reefs through aquaculture and reef restoration.

Gippsland Lakes

Scott spoke about the early records of Australian Flat Oyster from Gippsland Lakes being in 1896 around Sperm Whale Head. A small Australian flat oyster dredge fishery operated for a short time in the 1920s between Fraser Island and the Barrier.

The Gippsland Lakes once supported extensive areas of blue mussels. A mussel dive fishery operated from the 1970s’ to 1990’s with an estimate of 550 tonnes being harvested.

There are currently some sites where blue mussel beds persist e.g., Bell Point near Metung and adjacent to some jetties and marine structures. Australian flat oysters still occur, but in very low abundance with no reef structures.

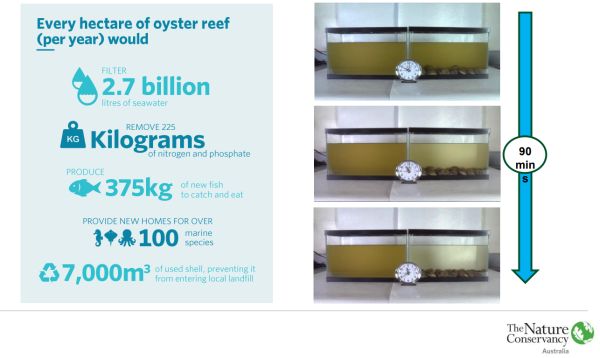

The role of shellfish in improving water quality

Scott spoke about the important ecological role of shellfish in filtering nutrients and sediments from seawater. One native flat oyster can filter 200 litres of water per day. On a larger scale 2000 native flat oysters can filter an entire 25-meter swimming pool in a day.

As well as imporoving water quality, shellfish reefs provide habitat for increased marine biodiversity, supporting many species of fish and invertebrates.

Restoration of shellfish reefs

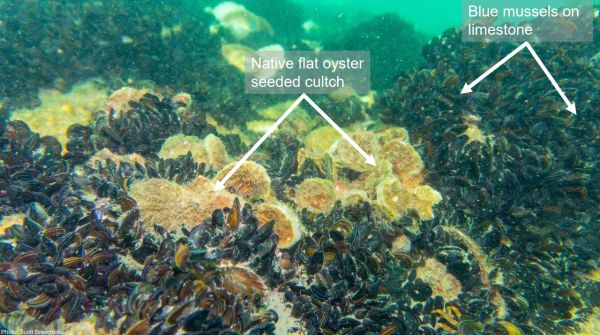

Modelling is carried out to identify the most suitable sites. Once permits and approvals are obtained works can commence. The process requires constructing a reef base using local limestone to form a secure substrate onto which oysters and mussels can be seeded. The aim is to recreate a natural ecosystem which once existed.

Construction of reefs

Aquaculture and seeding

The oyster larvae are held in aquaculture tanks where they can settle out on recycled scallop shells to form oyster spat. Scott explained a lot of work went into obtaining and cleaning the 4 tonnes of scallop shells used for the oyster larvae to settle and grow on. The process produced about 3 1/2 million oysters for reseeding the new reef. When the spat is ready the scallop shells containing the oyster spat are moved to the new reef and put in place by divers.

Challenges and lesson learnt

- Regulatory approvals – a long lead time needs to be factored in to obtain approvals. Streamlining the approvals process can help overcome problems.

- Timelines and funding cycles – often the funding timeframe is shorter than the approvals process which presents difficulties in realising the projects and carrying out adequate monitoring to measure the success of the project.

- Costs – unexpected rises in machinery hire and labour combined with weather events can easily cause cost increases which in some cases has required the size of reef to be scaled back

- Construction contracting – it is more economical to do one larger build rather than a series of smaller builds as there are economies in scale associated with machinery, plant and equipment. Skills in dealing with large construction contracts help with the process.

- Rock supply and load out facilities – obtaining the limestone which meets specific specifications can be difficult and often requires quarrying. Storage of the rock prior to loading on a barge also needs to be planned.

- Sourcing broodstock – finding a source population of flat oysters can be difficult as well as factoring in delays in collection due to climatic events such as floods or bad weather.

- Availability of suitable sites – because the process of identifying a site needs to go though a complex process of selecting the most beneficial site combined with stakeholder input the size or location of the new shellfish reef can change.

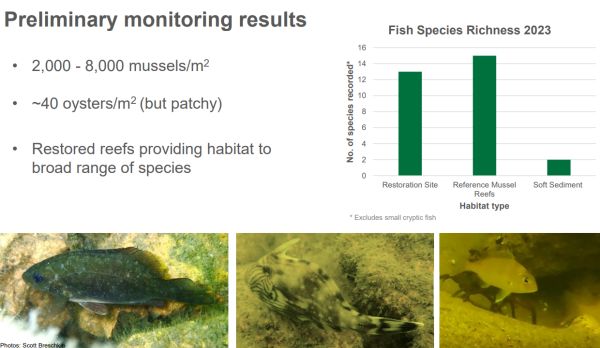

Results

Scott discussed the success of the project in Gippsland Lakes. The new shellfish reefs have been occupied by re-seeded oysters as well as self-seeded oysters and mussels leading to a sustainable shellfish reef.

Scott pointed out the reefs have provided new habitat for a range of species such as seahorses, a variety of fish and of course the flat oysters and blue mussels.

Reef Builder: Rebuilding Australia's lost shellfish reefs

Scott thanked everyone involved in the Gippsland Lakes shellfish reef restoration project.

Unfortunately there was no time for questions.